Project Unlock – What’s Up with Caging the Mentally Ill in China?

Over at the new blog – China Law Translate – Jeremy Daum has translated two recent mainland articles about individuals with mental illness and the impact of China’ new Mental Health Law (articles are here and here).

Over at the new blog – China Law Translate – Jeremy Daum has translated two recent mainland articles about individuals with mental illness and the impact of China’ new Mental Health Law (articles are here and here).

On October 26, 2012, after working on a draft law for close to 27 years, China finally passed its first Mental Health Law; that law took effect on May 1, 2013. Unfortunately, much of the focus of the foreign press about the new law has largely been on the changes to involuntary commitment and whether those changes will reduce the threat that political dissidents will be wrongfully and involuntarily committed. What’s been less of a focus has been the law’s impact on its actual target audience: those with diminished mental capacity.

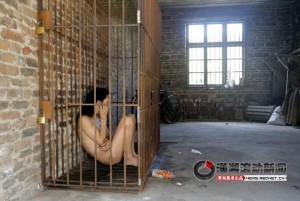

And that’s why Daum’s two translations – both recently published articles from the Chinese pres s – are interesting. Both focus on the plight of the mentally ill. Both examine the all too prevalent practice of caging severely mentally ill individuals.

The pictures that accompany the articles – photos of individuals chained and in cages, some of whom are stark naked – are shocking to say the least. And it would be easy to conclude that this reflects the callousness of a culture toward the mentally ill. But nothing could be further from the truth – if anything, the caging of these individuals is a result of the dire situation of mental health care in China, especially in the rural areas.

In “Cage People,” the Chinese reporter estimates that in Hebei Province alone 100,000 severely mentally ill individuals (usually considered  people with schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, etc.) are kept in cages as their only form of treatment. Although the reporter gives no citation for this number (thus use this number with caution), the use of restraints and cages has been well documented in other sources. In a 2011 World Psychiatry article entitled Mental Health System in China: History, Recent Service Reform and Future Challenges which examined China’s first experimental national mental health program – known as 686 Program and adopted in 2004 – the authors note the need for the program to include support for unlocking and freeing mentally ill individuals and finding treatment for them.

people with schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, etc.) are kept in cages as their only form of treatment. Although the reporter gives no citation for this number (thus use this number with caution), the use of restraints and cages has been well documented in other sources. In a 2011 World Psychiatry article entitled Mental Health System in China: History, Recent Service Reform and Future Challenges which examined China’s first experimental national mental health program – known as 686 Program and adopted in 2004 – the authors note the need for the program to include support for unlocking and freeing mentally ill individuals and finding treatment for them.

Lack of Mental Health Professionals

More than anything, this caging is a last resort in a system that has provided little financial support and few specialists in mental health. China estimates that over 100 million people suffer from some form of mental illness; 16 million of those suffer from severe mental illness. According to Mental Health System in China, China only has 16,103 licensed psychiatrists and 24,793 licensed psychiatric nurses; in other words, 1.24 licensed psychiatrists for every 100,000 people and 1.91 licensed psychiatric nurses for every 100,000 people. China is far below the global average, where there are 4.15 psychiatrists and 12.97 psychiatric nurses per 100,000 people. Id. As a result, it’s not surprising that 91.8% of all the mentally ill in China never seek help. For those with severe mental illness, 27.6% never receive any type of help and 12.0% of the severely mentally ill only visited non-mental health professionals. Id.

Social workers, who are key in a community-based mental health care system, are few in China. However, China is rapidly expanding its program, with the goal of training 3 million social workers by 2020. See Renne C. Lee, UH Aids China in the Developing Social Work Profession, Houston Chronicle (Mar. 4, 2013).

Disparity Between Rural and Urban Areas

But what makes that shortage even worse is that since the economic reforms, there has been a brain drain from the rural clinics to more profitable hospitals in the urban areas. See Yanzhong Huang, The Sick Man of Asia, Foreign Affairs (November/December 2011). Even though the Chinese government has recognized the need to institute a community-based care model for mental illness, where patients are not all hospitalized but instead are treated while remaining in the community, the Chinese government still expends much of its resources on psychiatric hospitals. See Mental Health System in China. This inherently means that money will flow to the urban areas.

Lack of Adequate Insurance and Funding to Rural Health Care Services

Finally, even with the reforms of health care funding, especially in the rural areas, mental health care is still too expensive for many Chinese. According to WHO, only 2.35% of China’s total health budget is spent on mental health (in the U.S. 5.6% of the national health care spending is on mental health – see Washington Post article); as of 2011, less than 15% of China’s population had insurance which covered mental health (although 45% of US mental health patients cite cost as a major burden). See Mental Health System in China.

Due to these factors, many severely mentally ill in the rural areas have only their families to take care of them. With little to no treatment, these families sit by while their relatives’ illness only gets worse. As a last resort, these families resort to restraints, not because they want to but because they have no choice.

Does the Mental Health Law Change the Current Situation?

Chapter IV of the Mental Health Law– “Rehabilitation from Mental Disorders” – creates a community based model of care which should limit

hospitalization to only necessary situations. This type of model allows those with diminished capacity to be integrated into society and is in line with China’s commitments under the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (which China has ratified and the U.S. still has not). Rural and village governments are required to assist those families obtain the services they need. This assistance includes financial assistance.

Unfortunately, the law leaves the funding of what could be a useful framework to the local areas. For already impoverished villages, they just don’t have the resources to carry out their responsibilities. As Daum’s translation of “The Need to Promote the Mental Health Law” demonstrates, even when families apply for their legal mandated “Minimum Subsistence Allowances,” the local fund is often inadequate and does not enable them to seek the medical help their relative needs; there will still be out of pocket costs that are too high for many villagers.

As Huang Xuetao, a lawyer at the Equal Justice Initiative, noted in the article, the hopeful prospects of the Mental Health Law are diminished by three things: (1) the lack of education to the people about the protections of the new law; (2) the lack of funding for mental health care and (3) the government’s lack of attention to the matter.

Until those factors change, especially the last two, China’s Mental Health Law will not achieve its objectives. However, these frank articles in the Chinese press – soon after the Mental Health Law took effect – might be a positive sign that change is on the way.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email