An Uncomfortable Truth: Use of Criminal Law in China’s Economic Development

Over at the Council on Foreign Relation’s China blog, Prof. Margaret K. Lewis of Seton Hall’s School of Law has written an interesting and timely piece about the role that criminal law plays in advancing China’s economic “miracle.”

As Lewis notes, and following up on recent articles in the New York Times (see here, here and here), China’s civil legal system and its regulatory state largely failed in dealing with some of China’s new economic problems – namely food safety, financial markets and environmental degradation.

But as Lewis goes on to highlight, this failure of the civil and regulatory systems does not mean that the Chinese government has not tried to stem these problems. In fact, as Lewis observes, it has, through the use of the criminal law. Recently, the Chinese government has stepped up the threat of severe criminal sanctions, including the death penalty, in an attempt to try to police this situation.

Lewis’ blog post is based upon her new research regarding how, since Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 “Reform and Opening” policy, the Chinese government has used the criminal law to propel its economic development. See Margaret K. Lewis, Criminal Law’s Contribution to China’s Economic Development (August 1, 2013). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2298923.

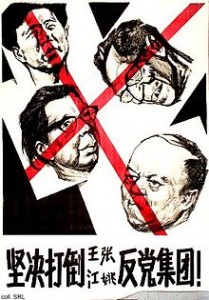

In fact, one of Deng’s first actions after assuming leadership was to publicly prosecute the Gang of Four, signaling the changing of the guard from

political extremism to a focus on economic growth. From there, Lewis recounts the formation of many of the laws that would underpin Deng’s policy of economic growth, showing that the intention of many criminal laws was to find the “growth-enhancing sweet spot.” It’s no wonder that today in China, economic criminal liability is much broader than in most other developed countries including the United States.

Lewis’ well-researched analysis makes a strong argument for her point: that you cannot analyze China’s economic growth without looking at how it has used the criminal law to assist in that growth. But even still, it leaves you uncomfortable – there is something about the use of criminal law to propel growth that seems at odds with its purpose. This Lewis notes is likely more the result of how the West has come to define patterns of economic growth. To achieve a sustainable market economy, the government sets in place a regulatory state with certain ground rules and then lets the actors – usually companies and individuals – duke it out within the confines of an independent legal system.

But that is not what is going on here in China and it’s this bucking of the traditional historical trajectory of growth that forces scholars to look elsewhere for its explanation. In China’s case, that elsewhere might be the criminal law.

“Criminal Law’s Contribution to China’s Economic Development” is a must read for anyone who wants to understand the relationship between law and economic growth in an authoritarian state. But it also raises many questions – is this use of the criminal law sustainable? Can China solve its regulatory failure problems through state-dominated use of the criminal law? Lewis examines a few problems with its usage, especially in attempting to deter official corruption where the Chinese Communist Party is too hesitant to prosecute its own. She also explores the use of economic criminal liability to suppress dissent that officials determine is too “destabilizing” to development.

From Lewis’ review of recent criminal legislation, interpretations and call for greater criminal liability, it becomes obvious that she is right – the Chinese government is attempting to use criminal law to support its market reforms. But in a country of 1.3 billion with a land mass close to the size of the United States, how sustainable is this approach? That is a question that we hope Prof. Lewis answers in her next article.

From Lewis’ review of recent criminal legislation, interpretations and call for greater criminal liability, it becomes obvious that she is right – the Chinese government is attempting to use criminal law to support its market reforms. But in a country of 1.3 billion with a land mass close to the size of the United States, how sustainable is this approach? That is a question that we hope Prof. Lewis answers in her next article.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email