Book Review: Paul French’s Midnight in Peking

Paul French describes his gripping new book, Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China

Paul French describes his gripping new book, Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China, as a belated quest to bring justice to a young woman, brutally murdered 75 years ago in Beijing. But the story is equally as applicable to the present, highlighting that our criminal justice system — and with the case of Bo Xilai, China’s criminal justice system — can easily fall victim to political agendas, singularly-focused investigations, and prejudices about who can and cannot commit a crime.

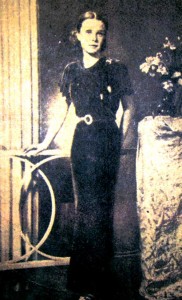

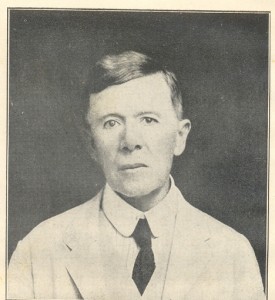

Midnight in Peking opens on a dark, cold morning in January 1937, in the dying days of old Beijing. A young white woman’s mutilated body is found near the haunted fox tower by an old Chinese man who is up early walking his caged bird. The body turns out to be that of 19 year old Pamela Werner, daughter of E.T.C. Werner, a former high-ranking British diplomat, China scholar, and single father who raised his daughter outside of the gated-off, foreign Legation Quarter of Beijing.

On the eve of the Japanese invasion, it was a murder that distracted Beijing as much as it obsessed it. And rightfully so. For the murder, and French’s amazingly detailed account of it, uncovers the debaucheries of some of foreign Beijing’s most elite, a young girl experimenting as a woman, and the official cover up that followed. On the eve of World War II, there was no way that British officials would allow the Empire and its respectability to lose face, even if it meant short-changing a police investigation and letting a diabolic murderer to go free.

French’s talent lies in his ability to transport the reader back to 1937 Beijing, back to the Grand Hotel des Wagons Lits, back to the Badlands where seedy expat Beijing lead much of its life but rarely talked about it within the Legation Quarter. French also makes the characters come alive – with his seven years of painstaking research into the official criminal investigation and Pamela’s father’s own inquiry, French knows what each of the characters were doing, writing and saying at the time.

Midnight in Peking is known as a work of “literary non-fiction,” presenting the facts almost as a novel but unable to take any of the liberties that a work of fiction could permit. In reality though, the work has more of the drama of a good closing argument – a winning closing argument – presenting the facts,debunking the police’s simplistic conclusions (including that it was a Chinese who did it; who else would kill and mutilate a body), and thoroughly presenting a stronger theory of who did it, a theory that the reader eventually adopts.

Midnight in Peking is a remarkable read, a page turner that kept me in one Friday night just to find out who did it. But it is not just a story about the past. Sitting there, reading about a British murder investigation in China and seeing the prejudices that the police held about certain incidents, particular people and specific facts, made me think of the recent re-examination of the 1979 Etan Patz kidnapping case that is currently transfixing New York City. In that case, it appears that the police misjudged suspects and had a singular focus on a specific interpretation of the facts, even with little facts to back that up. Some 50 years after the Pamela Werner murder, police in New York City were making the same mistakes. Fast forward 33 years to today and most likely these same types of mistakes are still being made.

But more than anything, the book also demonstrates the susceptibility of any criminal justice system to power and politics. E.T.C. Werner was an outsider to British expat society of 1937, and not just because he chose to live outside of the Legation Quarter. That pissed people off and when it came time to investigate the murder of his daughter, Werner, as an outsider, became a suspect. The murderers that French eventually uncover were not just accepted in British society but considered the elites of Beijing. That acceptance – and the fact that the British diplomats didn’t want a scandal on their hands – allowed them to live their lives as free men. Ultimately politics – both individual as well as national – proved more important than justice. Even when Werner conducted his own investigation and uncovered many of the lies of key suspects, British diplomats continued to ignore his pleas for justice for his daughter.

Not surprisingly, when reading French’s book, the Bo Xilai case – where Bo’s wife is accused of murdering a British national – was not far from

my mind. Given the politics involved in that case and the fact that perhaps Bo became an outsider to the Party system, it makes one wonder about the accuracy of the story that the Chinese government is currently presenting to the press. If it could happen in British Peking in 1937, it can certainly happen in Chinese Beijing in 2012. Likely, no criminal justice system is immune to political pressure. It would be foolish – and dangerous – to think that any system is impervious.

Midnight in Peking is a remarkable story, wonderfully written and with characters that just come to life – some you love, some you hate and some you just despise. For those who want to be transported to the past, Midnight in Peking

is your ticket there; but for those who want to understand the present, more precisely the mistakes inherent in any criminal justice system, Midnight in Peking

will take you there. Whichever trip you decide to make, French will take you on a fun ride.

Rating:

Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China, by Paul French (Penguin Books, 2012), 272 pages.

French also has a great website about the book, including his own explanation as to what propelled him to write the book and a walking tour of Pamela’s Beijing (with downloadable podcasts). For anyone who does the walking tour, I would be interested in you take of it. Please comment below!

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email