Book Review – Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China

Huang Xueqin, a 30-something freelance journalist in the southern Chinese city of Guangdong, doesn’t look like a hardened criminal. With a playful smile and wearing an Annie Hall-style hat, Huang seems like a friendly sort, with maybe a mischievous side. But make no mistake, Huang is a fierce advocate for women’s rights, being one of the public figures behind China’s nascent #MeToo movement after coming out in 2017 about her own workplace sexual assault. She’s written extensively on other women who have been sexually harassed and assaulted and, in 2018, conducted an online survey of female Chinese journalists finding that almost 85% had experienced sexual harassment on the job, with almost 60% of those remaining silent.

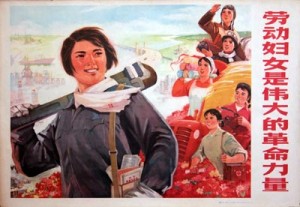

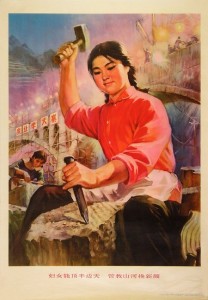

It was that activism that landed Huang in a Chinese detention center. And on Friday, after holding her for three months under suspicion of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles,” a crime under China’s criminal law that has been used almost exclusively to silence peaceful critics of the Chinese government, Guangdong police finally freed Huang. In a country where its founding leader once said that “women hold up half the sky,” it seems odd that a women’s rights activist would be considered a pariah, someone that the Chinese government has to deal with criminally.

But Leta Hong Fincher,[1] in her recent book, Title: Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China

, explains precisely why the Chinese leadership trembles at the idea of women calling for their rights. Identifying China’s current leadership as “patriarchal authoritarianism,” Fincher, in her well-researched and insightful book, shows that unlike other social movements in China, these feminist activists are not just seeking a more open society or looking to fulfill the promises of equality under Chinese law. As Fincher shows, if you take this feminist movement to its logical conclusion, only by overturning the current political and cultural order can these women achieve equality in China.

Fincher comes to this damning, powerful conclusion largely through the stories of five feminist activists who were detained for 37 days in 2015 and became known as the Feminist Five. This choice – to tell the history of China’s feminist movement and forecast where it is headed through these women’s personal narratives – is what makes this read an engaging page-turner. Not surprisingly, Fincher was previously a China-based journalist and she brings that reporter’s eye for detail and desire to understand the characters behind the story. And this is necessary because what caused the Feminist Five to end up in detention – also on suspicion of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles” – seems completely ordinary, and defies logic that this would be something that would scare any government, let alone China’s: they were just going to give out leaflets and stickers on public buses calling for the end of groping and provide women with information on how to report such an incident.

But for the Chinese government, this was a serious offense and the women needed to be broken. Through in-depth interviews, Fincher retells, for the first time, these Feminist Five’s harrowing experiences during 37 days of detention. They were subjected to physical and psychological torture: the police took away the women’s glasses, making them unable to see; interrogation was constant to the point that one woman needed medical attention; intense light, only a few inches from their faces, shown brightly in their eyes; medications were denied; and each was told about the threats made against their parents or children. These women talk about the emotional toll that these interrogations had on them, making each question whether it was worth it. But in the end, each remains committed to the cause, finding strength in the support of other Chinese feminists and inspiration from women activists abroad.

While the Feminist Five, and other Chinese Feminists’ stories makes the book a lively read, Fincher doesn’t shy away from more academic arguments to further support her argument of the Chinese government’s “patriarchal authoritarianism.” She examines societal institutions: the lack of any women in positions of power in government; the prevalence of domestic violence in China; the failure to enforce the Domestic Violence Law; the pressure on women to marry and the shaming of single women (this was the focus of Fincher’s ground-breaking book, Leftover Women); the lack of career options for most women; nationalist rhetoric filled with misogyny; and seeing women solely as reproductive vessels.

Betraying Big Brother is a necessary read to understand the role of women in Chinese society and why the feminist movement may be one of the few social movements to overcome the Chinese government’s persecution. Make no mistake, Fincher is not a neutral observer; she admits as much in the Introduction stating that she is a convert to the cause and friends with many of the women she writes about. But this doesn’t hinder her scholarship; she finds sufficient evidence to support her arguments. Fincher believes that China’s feminist movement will achieve its goals: there is broad discontent among women in China that crosses class lines and the creativity of these activists give them the uncanny ability to constantly influence public opinion even in light of the government’s crackdown. But while Betraying Big Brother

is full of hope, Fincher is not naïve. She knows that the Chinese government will not give up without a fight and that things are going to get a lot worse for these activists before they get better. Huang Xueqin is a recent case in point.

Rating:

Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China, by Leta Hong Fincher (Verso 2018), 205 pages

***************************************************************************************************************************

[1] In the interest of full disclosure, Fincher is a colleague and friend .

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email