Rachel Stern on Environmental Litigation in China – Success or Failure?

China Law & Policy continues its interview with UC Berkley professor and noted China environmental law expert Rachel Stern. In Part 1 of the

interview, Prof. Stern discussed what an environmental movement looks like in an authoritarian regime.

Here in Part 2, Prof. Stern gets to the heart of the matter – how are China’s environmental laws put into practice? What does environmental litigation look like in China? What are the advancements its made and what are the challenges it still presently faces? Prof. Stern addresses all of these issues and then also looks at the positive developments in administrative litigation in the environmental field.

Click here to listen to the audio of Part 2 of the interview with UC Professor Rachel Stern

Length: 20 minutes (audio will open in a separate browser)

To listen to or read Part 1 of this interview, click here.

**************************************************************************************

EL: So you do have these [environmental] laws and presumably with these laws you would see an increase in environmental litigation. Is that what your studies have shown? Has there been an increase in citizen litigation of environmental claims in China? What is the status of that litigation?

RS: I wish we had better data on that. [Laughing]. That would be really nice if you were writing a book on environmental litigation in China.

All research is limited by the statistics the Chinese government chooses to release. The data on the numbers of environmental lawsuits have been really piecemeal. So the best data I have is from a Supreme People’s Court work report from 2011. They announced that there were about 12,000 pollution compensation lawsuits the year before – so that would be 2010. The volume of litigation going through the legal system in general is about 4.1 million civil cases a year. So we have a tiny fraction. So it would be very small but that is true in all legal systems. Environmental lawsuits are always a pretty small portion of what is going on.

EL: So in the United States, so do you know what percentage are environmental cases?

EL: So in the United States, so do you know what percentage are environmental cases?

RS: I don’t know the exact percent but the numbers would be roughly comparable. Courts are mostly busy handling divorce, family matters, the kind of stuff that is much more every day. I’m pretty sure that the number of environmental lawsuits [in China] have been rising because there is clear data that the number of environmental disputes have been rising. So if disputes are going up, my expectations is that lawsuits are going up as well.

EL: And in terms of these lawsuits – keeping in mind that a lot of people who read this blog are American students of law or students of American law – what do these cases look like? Are they largely angry citizens bringing these suits on their own as pro se? What role do non-profits play? Is there a Sierra Club or an NRDC in China? And how do these cases play out in the courts in China?

RS: Most of the cases are what lawyers call tort cases. The cases that I am looking at are civil [tort] cases.

EL: A tort case is basically a case where someone has been injured?

RS: Yes, exactly. So they involve monetary compensation for damages. The archetypical case that always think about is: there is a chemical factory upstream and there is a guy farming fish downstream and there is a chemical spill at the chemical factory and the fish farmer wakes up and all of his fish are dead and he wants 10,000 renminbi [Chinese currency] from the chemical factory to pay for the dead fish. That’s where the average case is in the Chinese legal system. It’s not about environmental rights per se, it’s about money, it’s about monetary damages, and it’s not necessarily about health.

When I was writing this book in the end of the first decade of the 2000s, lawyers were trying to get money for health claims for pollution victims and that was very much on the frontier. If you could get money for a cancer victim and link that case to pollution, that was a huge victory. That was not the mainstream case that was going through the legal system at all.

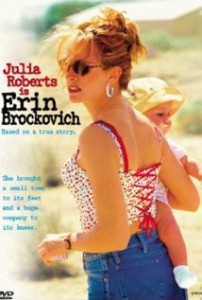

EL: And is that more of a result of evidence issues to show that the — because I mean I know even in the United States, if you see Erin

Brockovich – which you mention in your book which I thought was funny – proving that people’s cancer is a result of a certain chemical, is hard even in the United States. Is that hard to show even more in China where presumably you wouldn’t have the resources because lawyers aren’t paid maybe in the same way.

RS: Yeah, I think there are two things going on. I think the issue you are talking about is causation which is really hard. This is so hard in all environmental law suits; it doesn’t matter if they are happening in China or Zambia or New Jersey – that link is always super hard. And it’s really hard for Chinese judges to figure it out. Here in the US we would have competing experts dueling it out over what the ground water patterns show. In China what they tend to do is they tend to outsource this issue of causation to an appraisal agency. So judges impulse is usually to find a neutral third party to write something up.

One of the big issues that came out of my field work was that the quality of these appraisals are all over the place. Sometimes they are done really conscientiously by people with a really strong background in environmental science and they’re really good. And sometimes they’re really awful and done by people who have no idea what they’re talking about. There is not a lot of quality control.

So that’s the critical piece of evidence when it exists in these cases and one of the steps forward for Chinese environmental litigation to work better is that you have to control of the quality of these appraisals better than has been done in the past.

EL: In terms environmental cases getting into the court system – I know a lot of people talk about how the courts don’t have to take a case…

RS: No, they sure don’t.

EL: How successful are environmental cases in making it past that first hurdle?

RS: It’s really hard. I think that’s actually the biggest stumbling block is getting the case into court and convincing judges at the case acceptance

division of the court [li’an ting -立案庭] that this is a good way to handle the dispute. That’s the moment in which the case is likely to be turned away. The best data I have suggests that if you get your case accepted by the court as a plaintiff in one of these environmental lawsuits, plaintiffs will get something, not everything they want, maybe it’s just one renminbi, but they will get something 50% of the time. So the big stumbling block is getting it in the door and convincing judges that this is a case that they can deal with, that it is within the court’s jurisdiction and realm of possibility.

EL: You have the monetary relief, so you have to show damages for that guy whose fish are dead because of chemicals in the water. Do you ever see cases where they ask for injunctive relief, where they ask for the industry to stop polluting to shut down the industry or anything like that.

RS: So a very typical sentence in an environmental decision will call on the polluter to stop harm. It is not an injunction but that’s usually part of the decision. The problem of course is enforcement. It’s very rare for the courts to follow up and make sure that the decision is actually enforced.

So one of the more exciting things that have been happening is that some of the environmental courts have been working with the environmental protection bureau to establish monitoring of decisions after the fact to make sure there’s a cleanup plan and that it actually happens. But again that is really the frontier of where we hope environmental law is going as opposed to the mainstream of where it is right this second.

EL: I guess given all of that do you think there are successful environmental cases in China. You had talked in one of your chapters in the book about the Pingnan case where the villagers won on the law. They ostensibly won – the company had to clean up the pollution and pay a fine. But ultimately the fine amounted to such a small amount – $63 USD per person.

RS: I know, isn’t that a depressing story?

EL: It was very depressing.

RS: Especially because this was the most celebrated environmental lawsuit of 2006. So this is trumpeted as a major victory and then it is kind of the glass is half empty. It’s not that much.

EL: In your mind and I guess in some of the people who are on the forefront of the environmental movement in China and the judges in the environmental courts and the governmental agencies that deal with it, how do they define victory? Do they really see this [the Pingnan case] as a victory? Do they understand that…

RS: They would definitely see Pingnan as a victory. Not so much because of what the villagers got but because of the media attention the story got and the way in which it called attention to the issue and the way in which it re-framed the debate.

So the media attention itself is a victory regardless of what people actually get. The articles that came out of the Pingnan lawsuit are questioning the old economic-growth-at-all-costs model that has been on for so long. So in so far as the real story is about raising environmental consciousness and creating groundwork for the environmental movement, any lawsuit that gets national attention is a success.

But it’s hard to know. I would sometimes in my interviews, I would ask lawyers “can you tell me about a successful lawsuit?” And they would come back with a story and the punch line of the successful lawsuit for them was that the factory closed up and moved away. So then my next question is “where did it go?” The answer is often that it went to this poorer part of the province. So is that a real victory? It is for people who live in that place, but it raises real concerns about environmental justice and whether or not these lawsuits, if you take the nation as the unit of analysis, whether or not they are really doing that much to improve environmental quality. This is such a tough field, you have to celebrate every little success even it doesn’t add up to success on the level of Brown v. the Board of Education.

EL: When that [Brown] came down wasn’t enforced in a lot of places, it was just enforced in that one place and then the Supreme Court

decided to wait to integrate. So I guess it is kind of fair to see Pingnan as a victory because it did get media attention and did raise consciousness but then it was just a little bit of money for the people that were harmed.

RS: I know. I find again – just speaking in general – the plaintiffs tend to be pretty happy if they get any part of what they wanted. They really feel like the deck is stacked against them in these type of cases and if they get a fair hearing and if they get a portion of what they wanted, they tend to think that that that’s a success.

EL: What do you think are the major roadblocks to what we would define as success where the plaintiff is made more whole than they are being made right now? What are the major roadblocks you are seeing in environmental litigation in China?

RS: Well we already mentioned two of the really big ones – one is getting the case into court and convincing judges that this is part of their responsibility to hear these kinds of cases and [second is] improving the quality of appraisals so that they have a real scientific basis and judges can really rely on them. I think that those two reforms would go a long way toward improving the quality of justice in these kind of cases.

The third one is enforcement of decisions. Putting teeth in the idea that you have to clean up after a decision as opposed to basically pay off plaintiffs with a little bit of money. It would be the third thing. And I think for that really to work there would need to be cooperation between the court and the environmental protection bureau to a much a deeper degree.

EL: What are you seeing right now between the court and the environmental protection bureaus?

RS: Usually nothing.

EL: In China is it that when the court orders for the plant to stop polluting the water is it then the responsibility of the local environmental protection bureau [EPB]to enforce that?

RS: Right now it is kind of no one’s responsibility. It is kind of in a gray zone where nobody is going to be held to task for it, nobody is going to follow up, everybody knows that. One of the criticisms of China is that there is not enough judicial independence, the courts are too likely to communicate with other branches of government. The flip side is that you could really take advantage of that. If the courts were communicating with the EPB and making this cleanup part of the EPB’s mandate, that could really make a big difference. Of course the problem is that the environmental protection bureaus are chronically underfunded and understaffed so that probably needs to be addressed. But at least the possibility is there.

RS: Right now it is kind of no one’s responsibility. It is kind of in a gray zone where nobody is going to be held to task for it, nobody is going to follow up, everybody knows that. One of the criticisms of China is that there is not enough judicial independence, the courts are too likely to communicate with other branches of government. The flip side is that you could really take advantage of that. If the courts were communicating with the EPB and making this cleanup part of the EPB’s mandate, that could really make a big difference. Of course the problem is that the environmental protection bureaus are chronically underfunded and understaffed so that probably needs to be addressed. But at least the possibility is there.

EL: When I was reading your book, definitely these are problems in environmental litigation in China but honestly a lot of this seems to be problems in a lot of citizens’ rights cases – disability rights things like that. Do you think this is also a problem in other areas?

RS: Totally. Some of its a little bit specific like the issues of the appraisals, that’s a little special But problems getting cases accepted, problems getting decisions enforced, this is totally endemic to the whole legal system.

EL: Well, that’s positive, at least it is not focused on environmental issues. [Laughter]

RS: No, it is not personal.

EL: The other thing in reading your book, I think a lot of people outside of China because there has been so much press about China passing

so many laws one environmental protection, that in the Western press there is this talk of an environmental movement in China, you see protests. So you think oh, this is a hotbed of activity – stuff is really happening here. But then I read your book and I am like oh, no, not really. But when I did read your book, one of the hopeful things I did read it was there were parts where you talked about the success of administrative litigation in China. What’s been happening with administrative litigation in China in the environmental sphere and can you just describe more what that looks like vis-à-vis civil litigation.

RS: So the most hopeful thing that I found was not so much in terms of civil litigation. I need to give a shout out to Zhang Xuehua whose research this really draws on. What she found is that there is a part of the environmental litigation law that’s not that well know which is what call “non-litigation administrative execution cases.” I always have to look at my notes because I never get that quite right. But that’s what they are called and what it means – to put it in English – is that under the administrative litigation law, government agencies can bring lawsuits in court when their administrative decisions are not being followed.

What she found in Hubei province was that sometimes the environmental protection bureau brings these lawsuits in court to sue polluters who are not paying their fines and to get the court’s moral authority and help calling these polluters to task. So you can get this sort of synergistic relationship and alliance that can emerge between the EPB and courts. So between two parts of the Chinese government that are traditionally perceived as very weak. They can kind of help each other out. The court doesn’t have a lot of tools at its disposal but two things they can do is that they can detain managers of firms that are not paying up and they can freeze bank accounts. Plus they have some moral authority.

So if you put all of this together, sometimes the EPB bringing these lawsuits can scare polluters into thinking “wow the courts have gotten involved, the judges have shown up, now I have to pay.” And she’s [Zhang Xuehua] just describing this pattern – this alliance emerging – in just a few places. But it is really optimistic that there is that possibility of cooperation between these bureaus. They can get more done together than either one can ever get done on their own.

EL: So you’re seeing this in just a few places in China? Has it spread since she started investigating Hubei. Do you think this is a model that will spread throughout China?

RS: I don’t know. I hope so. There’s been quite a few of these non-litigation administrative execution cases in some of the environmental courts in Wuxi in particular and in Chongqing. In those two places this type of case makes up a large percentage of what the courts are dealing with. There it has provided real way for the court to get enough cases to justify its existence. I am optimistic that this may be a path forward for the environmental courts in particular. It kind of works out well for both sides. The EPB brings cases and that is a way for the environmental court to expand its case load and reach a more stable footing.

EL: In terms of the EPB, the environmental protection bureaus on the local level and then – your book does talk about how even though they still are underfunded and understaffed it does talk about the huge increase in the number of staff that they have had over the past decade and that in 2008 the National Environmental Protection Administration was raised to a ministry-level which gives it more power. Is this changing the culture of people who work there. What are the types of people who work there. I know in the United States a lot of people who work at EPA, they are very into the environment and they will often go to NRDC or Sierra Club. Is that culture you are starting to see created in the government agencies that supervise environmental [issues] or is there still a lot of people where it’s just a job?

RS: The visible upgrade in status for the environmental protection bureau employees over the last ten years has been positive. There is more of a feeling of pride in their work as you would expect as the work has more visible importance placed on it. I think there is a ways to go before everyone who works for the EPB is a dedicated environmentalist. In the interviews I have done with EPB officials the discourse is usually – it is about protecting the environment – but its mostly about finding more appropriate balance between economic growth and environmental protection. And recalibrating that balance so that it is more appropriate for the current moment in China. I think that makes sense for where China is right now and for the kind of rhetoric that is coming out of the central government. But it does strike me that there is a big gap between finding balancing point between economic growth and environmental protection and being a fervent and committed environmentalist as we might see here at least in parts of the EPA.

****************************************************************************************************

To listen to Part 1 of the interview with Prof. Stern, click here.

In the next post, China Law & Policy concludes its interview with Prof. Stern where she discusses the role that international NGOs have played and what she sees as the future of the environmental movement in China.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email