The Dangerous Historical Context of Trump’s ‘Chinese Virus’

Donna Chiu has dedicated most of her life to fighting for vulnerable New Yorkers. A petite, Chinese-American woman with a quick smile and contagious laugh, you would never think she would be able to take on some of New York City’s sleaziest landlords. But within the dark, dingy halls of New York City’s housing courts, she transforms into a pit bull, aggressively fighting for her clients, low-income tenants, and holding landlords responsible for their illegal practices.

But Chiu has a new villain to fight – the anti-Asian sentiment that is on the rise in the United States as a result of Covid-19 and a President who seems to take sick pleasure in constantly referring to the pandemic as “the Chinese virus.” Since Covid-19 has hit the shores of the United States, anti-bias crimes and incidents against Asian Americans have increased according to The World Journal, a Chinese language newspaper based in New York. In fact, since March 18, when President Trump doubled down on his use of the term “Chinese virus,” The World Journal has published an article almost every single day on bias crimes and incidents against Asian Americans in New York City. Perhaps even more telling are the wechat groups and Asian-American focused websites like Angry Asian Man that are awash in conversations about the increase in anti-Asian incidents and crimes.

“I have not been a target myself,” Chiu told me when I asked her about the impact of Trump’s constant reference to Covid-19 as the Chinese virus. But she was quick to tie Trump’s remarks to increasing xenophobia, explaining how it has changed her day-to-day life: “[It] has made me not go to certain places or enter certain stores because now I view it as a serious risk to my safety; I stay alert when I was still riding the train and try to avoid eye contact with strangers and walk swiftly – all ad hoc measure to avoid being a target.”

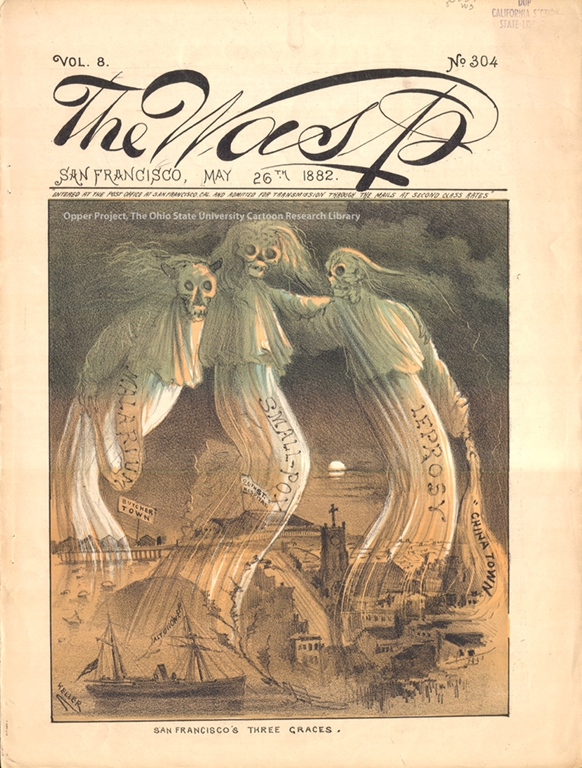

For Janelle Wong, a professor of American Studies at the University of Maryland, blaming Chinese people for Covid-19 was no surprise. When I asked Wong about her take on the increase of bias-related crimes against Asian Americans, she quickly put it in a historical perspective, going back to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, one of the United States’ most exclusionary laws. “Part of the justification for the exclusion was the idea that the Chinese were vectors of disease” Wong told me, sharing a cartoon from the time period to prove her point. In that cartoon – cover art for the May 1882 issue of the aptly-name magazine “The Wasp” – three skeleton-faced ghosts, one named malaria, one named smallpox and one named leprosy, ominously float over the city of San Francisco. The source for these menacing zombies? Chinatown as the cartoon makes clear in the lower right hand corner. The message? Exclusion of the Chinese is the only way to save the city.

For Janelle Wong, a professor of American Studies at the University of Maryland, blaming Chinese people for Covid-19 was no surprise. When I asked Wong about her take on the increase of bias-related crimes against Asian Americans, she quickly put it in a historical perspective, going back to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, one of the United States’ most exclusionary laws. “Part of the justification for the exclusion was the idea that the Chinese were vectors of disease” Wong told me, sharing a cartoon from the time period to prove her point. In that cartoon – cover art for the May 1882 issue of the aptly-name magazine “The Wasp” – three skeleton-faced ghosts, one named malaria, one named smallpox and one named leprosy, ominously float over the city of San Francisco. The source for these menacing zombies? Chinatown as the cartoon makes clear in the lower right hand corner. The message? Exclusion of the Chinese is the only way to save the city.

“It’s long been a trope that is easily used . . . but it’s been a while since a national leader has drawn [upon it],” Wong went on. “That is what is shocking.”

When questioned on his use of the term “Chinese virus,” Trump denies that it has any racial animus. For Trump, simply because the virus comes from China, it should be called “the Chinese virus.” He ignores the World Health Organization’s (WHO) repeated instructions to avoid using country names as the name of an infectious disease so as to prevent bias against groups of people.

Make no mistake, Covid-19 did come from China. And there are many aspects of the Chinese government’s handling of the outbreak that put the world at greater peril. It suppressed doctors from freely speaking about the virus which prevented the world from knowing earlier of the outbreak. And, even though the Chinese government had to know that human-to-human transmission was occurring by the end of December, when almost every day it saw the number of Covid-19 patients double according to government data leaked to the South China Morning Post, it denied such transmission until January 20, 2020.

Would the Trump Administration have used that extra time to better prepare the country to fight Covid-19, say by preparing sufficient tests or ensuring that hospitals had sufficient protective gear to get them through a possible pandemic? If current history is any guide, where we are all still anxiously awaiting widespread testing and our doctors and nurses are reusing face masks, likely not.

But still, Trump needs someone to blame for his gigantic missteps that are currently putting the lives of tens – if not hundreds – of thousands of Americans at risk. For Wong, getting many Americans to follow the script of China bashing is easy. Which means, given our history, that Asian Americans will inevitably be targets. Initially, Trump denied that his words would fuel anti-Asian crimes. But on Monday night, after a plethora of Democratic politicians, civil rights groups and average Americans condemned Trump for using “Chinese virus,” Trump attempted to walk back some of his words, tweeting that Asian Americans are “amazing” people and that spreading the virus was not their fault.

But likely that tweet won’t be enough to put the racist genie back the bottle. And, as Wong explained to me, this objectification yet again makes Asian Americans feel that they are forever the foreigner; that true belonging in the United States remains unattainable to non-whites, even those who may have achieved some modicum of economic success. Those doubts were exactly what attorney Chiu was wrestling with when I talked to her. “It doesn’t change a topic/issue that I’ve always struggled with – which is what are Chinese-Americans place in America? Are we second class citizens just like the way we are treated? And then with Covid-19. . . .I feel the climate is one where Chinese-Americans are not allowed to ‘feel bad’ for themselves because we are the cause of all this.”

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email