Remembering the politics behind a massacre

Thirty-four years later and even in the West, where we are allowed to remember the events surrounding the Chinese government’s June 4th, 1989 massacre of its people, there are things we have forgotten. We think of the Tiananmen protests as millions of students occupying the Square every day for months. But the protests had largely died down by the end of May 1989, with just a few thousand people left on the Square. We refer to Li Peng, Premier at the time, as the “Butcher of Beijing,” but it was Deng Xiaoping who was most eager for blood and had been plotting a military response since early May.

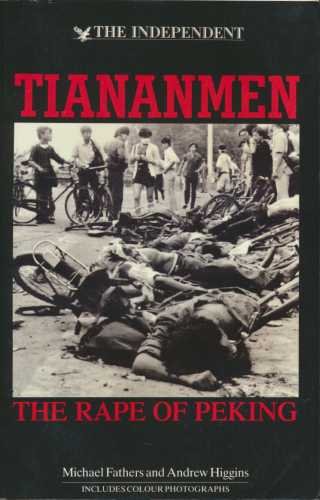

To help us remember is Michael Fathers and Andrew Higgins’ gripping, and, at only 148 pages, concise classic, Tiananmen: The Rape of Peking, published a few months after the June 4th crackdown. In 1989, Fathers and Higgins were The Independent’s China correspondents giving them front-row seats to the protests. More important though, were Fathers and Higgins’ well-connected government sources which allowed for their vivid descriptions of the factional infighting in the highest levels of the Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”). It is this insider knowledge that makes Tiananmen: The Rape of Peking an astonishing read, especially compared to today, where China is increasingly closed off and the inner workings of the Party are a guessing game. With their focus on the political power plays inside the Chinese leadership, Fathers and Higgins argue that the massacre was intended not just to subdue the Chinese people but to show Party officials that any dissension would be dealt with severely.

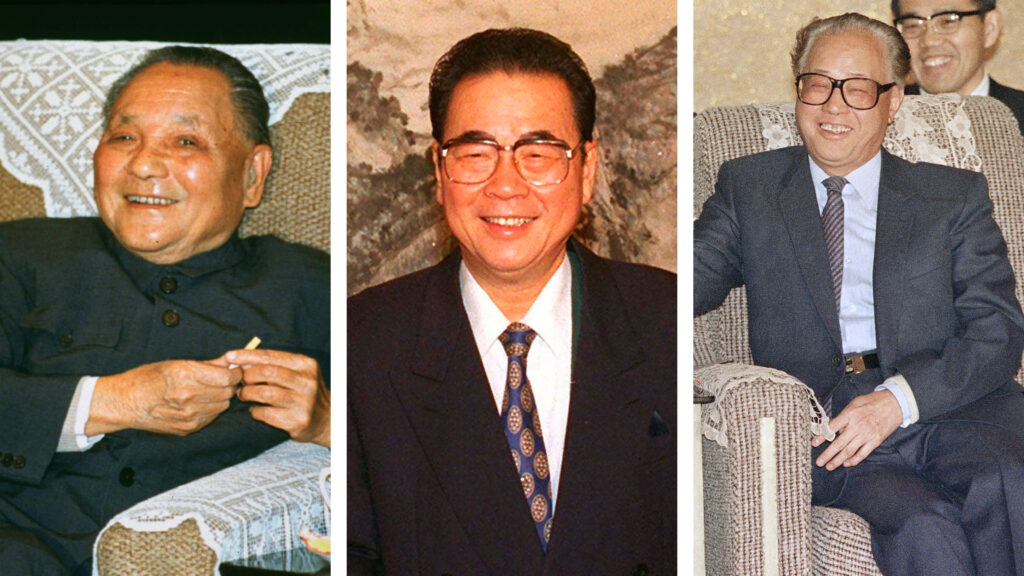

By the late 1980s, the CCP was fractured between two camps: the reformers, led by CCP General Secretary Zhao Ziyang who called for more economic reforms with some societal loosening, and the conservatives, led by Prime Minister Li Peng who wanted to maintain Party ideology. Deng Xiaoping, retired from government but still in charge of China, was generally a reformer. But as Fathers and Higgins show, above all else Deng was a political survivor, overcoming multiple Party purges in his lifetime and unseating Mao Zedong’s chosen successor, Hua Guofeng, to become China’s leader after Mao’s death. A year before the protests, as Fathers and Higgins point out, Deng and Zhao advocated for free market pricing. When record inflation hit the country as a result, it was Zhao who took the fall, not Deng. Li Peng, who opposed such unorthodoxy, saw his star rise.

In Tiananmen: The Rape of Peking, it is Deng’s desire to politically survive that made the massacre in Beijing inevitable. With 100,000 students marching to Tiananmen for reformer Hu Yaobang’s funeral on April 22 and demanding a dialogue with leadership, Deng saw the student protests as a threat to his absolute authority. Knowing that Zhao, the Party’s Chairman, held a more sympathetic view, Deng bypassed the chain of command, and while Zhao was on an official visit to North Korea, he convened a meeting of the leadership. Without Zhao, Deng and the conservatives dominated and they approved the publication of Deng’s provocative People’s Daily editorial that unequivocally condemned the student protests and referred to them as “turmoil.” For Fathers and Higgins,

“The editorial marked a crucial point in the evolution of an official response to the student unrest – the point of no return. The hardliners [conservatives] had published their manifesto. So great was judged to be its importance that it was made public before it had been printed in People’s Daily itself. That, at least, was part of the reason: the other part was more devious. A copy of the proposed text had been sent that same afternoon to Zhao Ziyang in North Korea….By the time he received the telegram, the text was already being released.”

Tiananmen: The Rape of Peking, p. 37

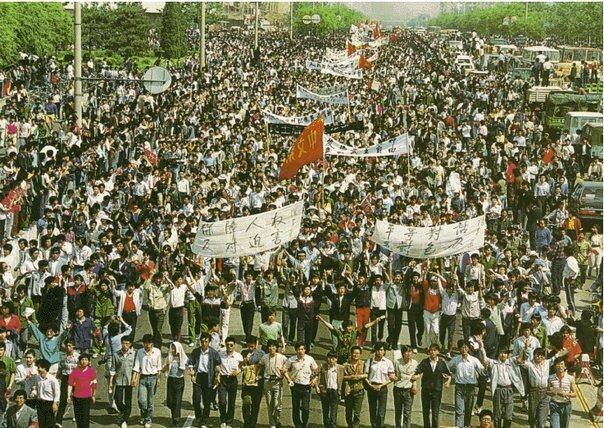

On April 27th, the day after the editorial’s publication, 150,000 students and Beijing residents marched to Tiananmen Square, demanding that the editorial be withdrawn in addition to general calls for greater freedom. On May 4th, an important day in Chinese history, tens of thousands of students again marched to the Square.

Zhao though was no political neophyte as Fathers and Higgins brilliantly portray in their chapter that describes his comeback. Simultaneous with the students’ May 4th protest, Zhao publicly stated that he believed the protests would “calm down” and there would be “no great turmoil in China.” With Zhao’s speech, it was now public that the Party was far from unified. “From the point at which Zhao delivered this speech, coexistence with Deng would become impossible” Fathers and Higgins grimly write.

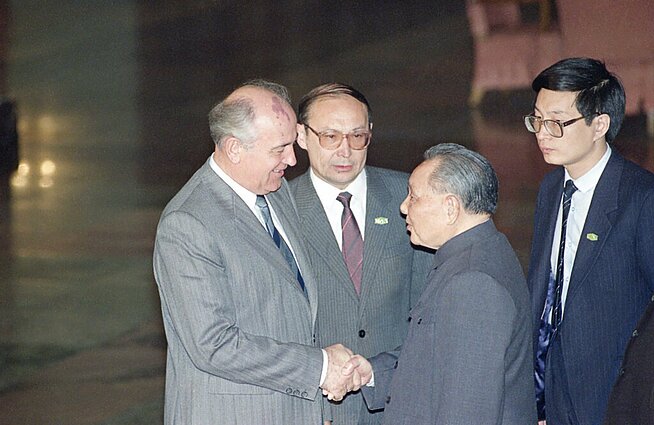

Zhao’s speech had its intended effect. The Square emptied and the students returned to their campuses. It seemed like the political winds were blowing in Zhao’s favor. But all that changed in the middle of May when the students, sensing the leverage that Soviet Union president Mikhail Gorbachev’s historic visit to Beijing could provide, began a hunger strike to last through his visit. 2,000 students participated and 10,000 more camped out on the Square in support. Before Gorbachev’s arrival on May 15, Zhao’s staff pleaded with the students to move their hunger strike to outside Zhongnanhai, the Party’s headquarters. To do otherwise they told the students, could severely damage the reformers’ efforts. But the students did not move their protests and on May 17, during Gorbachev’s visit, over a million people occupied Tiananmen Square. Joining the students were labor unions, professors, high school students and ordinary Beijingers, discontent with the status quo and excited for change. May 18 saw another million-strong on the Square.

With Deng’s loss of face before Gorbachev, Zhao’s strategy had failed. On May 20, Li Peng declared martial law and Deng called up the military to prepare for a crackdown. But as Fathers and Higgins point out, by the end of May, the protests had fizzled out. Although the Goddess of Democracy’s arrival on May 30th renewed some interest, only 5,000 students remained on the Square, and most of them were students from other parts of China. Two of the protests’ leaders – Wang Dan and Wu’erkaixi – had returned to their campuses. Summer vacation was only two weeks away. Time was on the leaders’ side.

But time was irrelevant to Deng and the conservatives as they readied the PLA to enter Beijing. As Fathers and Higgins recount, during the day on June 3, PLA troops began to march into Beijing. All were met by thousands of unarmed Beijingers who blocked the roads with either buses, cars or their own bodies. Instead of attacking, the PLA retreated. The people cheered and beckoned the retreating troops back out to celebrate the fact that the army did not turn on the people. A carnival-like atmosphere permeated the streets of Beijing.

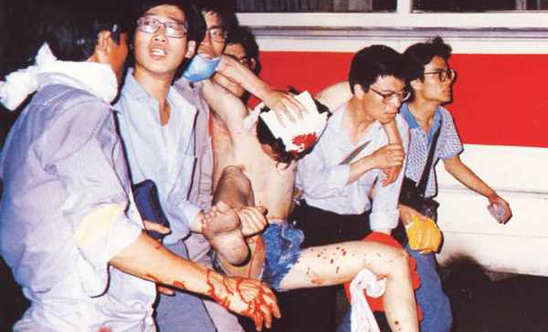

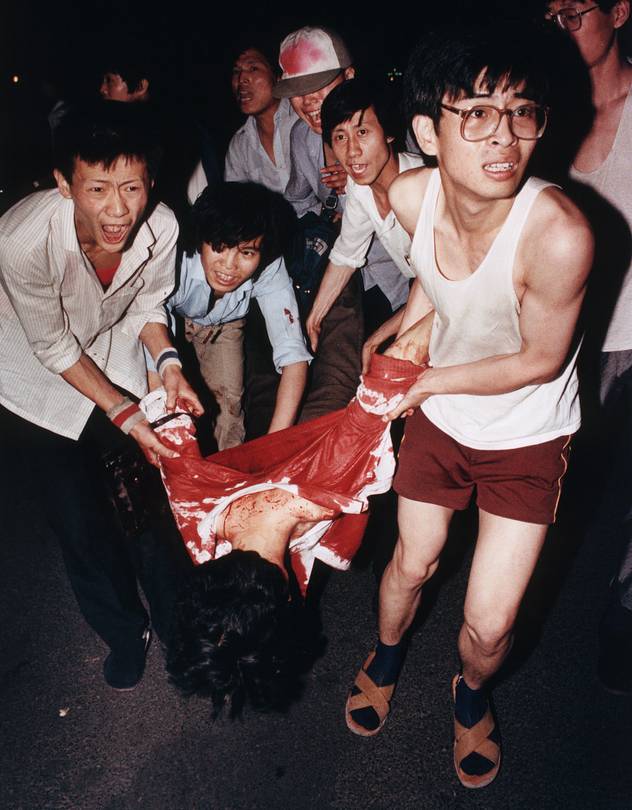

But a little bit before midnight on June 3, in the Muxidi section of Beijing, all of that changed. In their most powerful and heart-wrenching chapter, Fathers and Higgins portray the valiant Beijingers, over 5,000 of them, who tried to stop the troops from closing in on the Square. The crowd included factory and office workers, journalists and writers, and the children of CCP officials who lived in the high-end apartment complex overlooking the Muxidi intersection. Just like earlier in the day, unarmed soldiers were sent to disperse the crowd. Again, these soldiers retreated giving the crowd the sense that the people were victorious. This time though, the troops were replaced by new ones. With their AK-47s, the troops stormed the crowd, shooting wildly. In the first few minutes, deaths were in the double digits according to Fathers and Higgins. The army’s appetite for blood would continue as it marched down the main boulevard to the Square, meeting crowds of people at each intersection who thought they could stop the PLA. Instead, many were killed, either shot by soldiers or crushed by tanks. Even in the daylight hours of June 4th and long after the PLA had secured the Square, it continued to shoot into crowds of onlookers, adding to the civilian death toll.

For Fathers and Higgins, Muxidi shows Deng and the conservative’s diabolical nature. Sending unarmed troops into Beijing all throughout the day on June 3 was all part Deng’s plan Fathers and Higgins argue: to lure as many people out into the streets as possible so that when the PLA did open fire, casualties were certain. And it was no accident that the first murders happened before the apartment complexes that housed high-level Party members and their families:

Those who ordered the army into Peking, Deng and president Yang Shangkun, had done so not merely to disperse the mobs from the barricades, but to create a spectacle of forceful repression so shocking that it could not fail to cow anyone within the Party who had dared to sympathize with such defiance. The decision to open fire at Muxidi, in front of one of the Part’s main residential compounds, was a part of that spectacle.

Tiananmen: The Rape of Peking, p. 116

Tiananmen: The Rape of Peking is a fast-paced, comprehensive masterpiece that makes a frighteningly compelling argument that Deng Xiaoping, from the very first protests in mid April, wanted a violent crackdown so that his power would never again be challenged. For Fathers and Higgins, Deng is the ultimate villain and thirty-four years later, it is important that we do not forget this. But it is also essential that on this thirty-fourth anniversary of June 4th that we remember some of the heroes of Tiananmen that Fathers and Higgins highlight: those unnamed and unarmed civilians who took to the streets in a courageous effort to protect their city, mistakenly trusting that their government would never open fire on them.

Rating:

Tiananmen: The Rape of Peking, by Michael Fathers and Andrew Higgins

(The Independent/Doubleday 1989), 148 pages

Unfortunately this book is out of print which we hope that the publisher rectifies for the 35th anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown next year (2024). And, with the Chinese people unable to write their own history on this tragic event, we also hope that the publisher publishes a Chinese version (there is an Indonesian translation). Sometimes things jump the firewall; providing this book in Chinese will allow the Chinese people to learn about their fellow countrymen’s’ valiant efforts thirty-four years ago.

Used copies of Tiananmen: Rape of Peking can be purchased at Thriftbooks, Abebooks and Amazon.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email