Frank Upham – Our Man in Wuhan

Prof. Frank Upham

For the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre, China Law & Policy is conducting various interviews with eyewitnesses to this history. Today, we are joined by Professor Frank Upham, the Wilf Family Professor of Property Law at NYU School of Law, a faculty advisor to the US-Asia Law Institute, and a noted expert on both Japanese and Chinese law.

But back in the spring of 1989 Professor Upham was a researcher at Wuhan University faculty of law and as a result witnessed the pro-democracy protests that were also occurring in Wuhan, the capital of China’s Hubei Province. Unfortunately, there are no pictures of the 1989 Wuhan protests online. If people do have photos that they would like to share, please feel free to email me.

Listen to the full audio of this interview here (total time 40 minutes):

Additionally, you can read the transcript below or Click Here To Open A PDF of the Transcript of the Interview with Frank Upham.

CL&P: Thank you for joining us today. Let’s just go back to the spring of 1989. When did you arrive in Wuhan, and what brought you there?

FU: Yes. Well, it’s been 30 years. My memory is not going to be as detailed as we both might like, but I do remember that I was in Hong Kong. I had decided, after concentrating on Japanese law for most of the 80s, that I would like to study a little bit about China. I had gotten Chinese language earlier. I thought the best way to do that would be to go to someplace in China. I had spent time in Taiwan, but I wanted to learn about China. I chose Wuhan, because I didn’t want to go to Beijing, or Shanghai, or someplace that would already be, for lack of a better word, overrun with curious foreigners. Wuhan University is a good university, had a good reputation. I made contact with people in Wuhan, and I don’t remember exactly how I did that. I arrived in Hong Kong at some time in the middle of May. If we could find out, I mean, I could go back and search through my passports, but another way to find out when I arrived would be to learn when the US State Department issued a declaration, or announcement, or whatever the correct term would be, advising Americans in China to leave and advising Americans planning to go to China not to go to China.

Prof. Jerome Cohen

CL&P: And you still decided to go?

FU: Yes. I don’t know what I would have decided without a piece of advice that I got from someone. My former professor and now colleague at NYU, Jerry Cohen, was in Hong Kong at the time. I called Jerry, and I said to him, which I think he probably knew, “I’m scheduled to go to Wuhan two days from now, or three days from now, or something like that.” I had already heard from my wife back in Boston. She had a different opinion about whether I should go. She didn’t want me to go, of course. So, I asked Jerry, “Do you think I should go or not?” My memory is, we should maybe check with Jerry on this, is he said, “Well, I guess it depends on whether you want to be a part of history or not.” So, I thought, “Do I want to be a part of history?” I guess I decided I did, so I went.

CL&P: Okay. So, then when you arrived in Wuhan … First off, how did you get there, by train or by flight?

FU: Yeah. There were no scheduled flights to Wuhan from Hong Kong. There were charter flights. The charter flight was in itself a wonderful experience, because I was the only non-Asian person, I mean, there may have been Japanese or Koreans, on the flight. As I was waiting in line, I was approached by a travel agent, who was arranging for – I don’t know whether you’d know this phrase – a “laobing” [老兵]. These are old soldiers who came over with the Nationalist forces in 1949 to Taiwan. They were generally young, illiterate, and at least this person remained not young, but illiterate. This travel agent saw me, saw that I was reading documents in Chinese, introduced me to his client, and his client and I. . . .I helped him fill out all the visa forms for going into China, which was fun.

We sat together on the flight. Then when we got to Wuhan. . . .I don’t know whether you’ve seen the movie Casablanca, but at the end they’re leaving from the airport. Humphrey Bogart’s leaving from the airport I think. The Wuhan Airport at that time could have been the set for Casablanca. Wuhan had not yet been, quote, reformed, close quote. So, it was still like it had been for 20 or 30 years. We arrived at night. It was dark. I had called [Wuhan University]. There was no email. Anyway, I had made many efforts to contact Wuhan University and my contacts there to get them to meet the flight. I’d had no response. But I just figured, how far could the university be from the airport? I helped this laobing from Taiwan fill out his forms and so on.

Airport from Casablanca

We got to the airport. There was nobody to meet me. There was nobody at all. It was dark. There were a few light fixtures. I guess there must have been a customs of some sort, but most of the people on the flight were laobing, and they were bringing back televisions, cigarettes, all this stuff to give to their relatives in central China. And my guy was not an exception. So, we arrived, and I went to the line for foreigners, I mean, real foreigners – waiguoren [外国人] – and he went to the line for tongbao [同胞; “compatriots” – a term mainland China uses to describe Taiwanese]. Thank God he and his relatives who were meeting him waited for me. And I came out, and they were there. His relatives had done well. They had two black cars. They took me to Wuhan University.

CL&P: So, the kindness of strangers.

FU: Well, he wasn’t a stranger by that time, but yeah.

CL&P: I guess that’s true. So, when you got to the university, and I guess the next morning, what was it like? Were there students out protesting already? Were classes disbanded?

FU: I think they were already protesting. Yes. I was sent to the Chinese guesthouse. Wuhan, for reasons that still escape me, had been chosen by the French government as a center for the Alliance Française, which is their kind of propaganda wing, like the Voice of America. So, there was a foreigner’s guesthouse. They didn’t take me there, and I don’t know why, but they took me to the guesthouse for Chinese. It was full, and they gave me a room. Luckily it wasn’t raining. Anyway, when it rained, it had three different leaks. But anyway, that’s a different story.

I guess the demonstrations had begun, but first I checked in with the law faculty. Of course, to say that my arrival was not central to their interests at the moment would be an understatement. So, it was obvious that I was going to be on my own.

So, I just started to attend or observe the student demonstrations. I’m very careful about how I characterize that, because I’m an American. I don’t feel that it’s my role to try to influence Chinese political events, but I was incredibly curious. Of course, I wanted to see what I could see. So, I started out every day walking along with the marches. I would walk along the side. I didn’t chant. I didn’t participate. I observed.

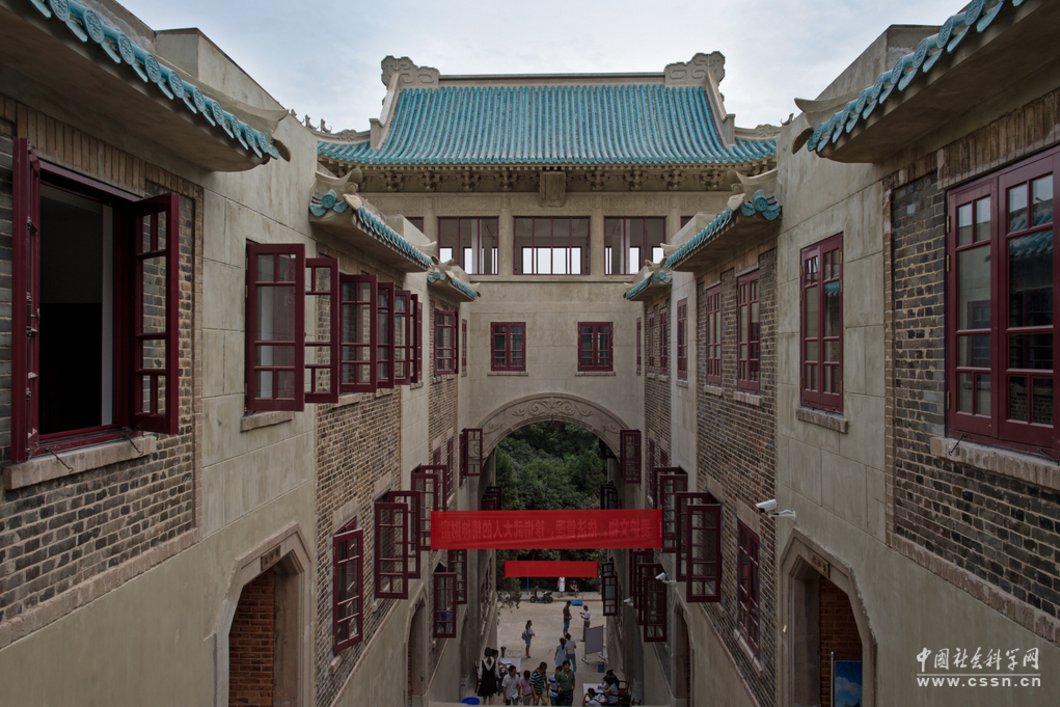

Wuhan University was founded in 1893 and has been able to maintain its historic buildings.

CL&P: And where were the marches going? Or were they on the university campus?

FU: They went downtown. They went from the campus to downtown. There’s a huge bridge in Wuhan. God, I don’t remember any of this stuff. I think Wuhan is the confluence of two rivers. So, essentially there is what looks like a big “Y,” and there’s a 16 lane bridge or something going over them. They would go there, and I would go along with them.

CL&P: How big were the protests? I’m sure you don’t know the numbers, but yeah.

FU: They started out being very big, huge. I mean, lots, and lots, and lots of people. They would always gather. . . .I don’t know whether they started at the Wuhan campus, but the people going from Wuhan [University] started at the Wuhan campus. So, every morning I would go down to where the people gathered. I was by myself, and nobody else was with me. I would then spend the day.

CL&P: So, as an observer walking with the protests, what did you observe was fueling the protests? Was it the same as what was fueling what was going on in Beijing?

FU: Besides what I read, I don’t know what was going on in Beijing. When I would talk to, and of course I did talk to people, they said that they didn’t want to overthrow the Communist Party, that they were Communists, some of them members of the [Chinese Communist] Party. But they wanted the Party to be democratic.

Protestors on Tiananmen Square in Beijing, 1989.

CL&P: Was it all just students? Because I know some of the reports from Beijing, it was also workers, from what you can observe?

FU: Yes. There were definitely other people. But I joined the flow with people coming from Wuhan University, so my people, the people I was with were students.

CL&P: Do you remember if you were there the day martial law was declared, around May-

FU: No. I don’t remember. I think it was May 19th?

CL&P: Yes.

FU: I don’t know.

CL&P: Do you remember, I mean, like how coordinated were the protests in Wuhan with what was happening in Beijing? Was information coming in from Beijing, or was there a complete-

FU: Oh. There was plenty of information. I don’t know if there was any coordination. That was above my pay grade. I was just walking alongside them [the students].

CL&P: But did you notice if anything, like if news from Beijing came in, it would cause the crowd to swell or anything like that, if you remember?

FU: When the news of the killings came in. . . .and that was something that I was quite puzzled by. When I first got there, these demonstrations were huge, and then I don’t know how many days I went out with them, but each day there were fewer people. The 4th [June 4, 1989], was that

CL&P: I feel like it was a Sunday.

FU: Yes. Maybe. And it was Saturday night.

Anyway, by that weekend, by Friday or Saturday, there were just not very many people [marching in Wuhan]. I thought to myself, “Well, the regime has outlasted them.” I don’t know what was happening at Tiananmen Square, the place, not the event, at the time, but my sort of vague impression is that things were slowing down there too, but I could be wrong. They certainly were in Wuhan. So, I thought to myself, “Okay. It’s ending.” I think I even stopped going, because there weren’t enough people to make it interesting.

CL&P: Was there any point before the June 3rd, June 4th incident up in Beijing, was there any point when you were in Wuhan that you were scared that? Because, I mean, if martial law had already been declared, was there anything scary about it that you thought, “Oh. Maybe I made the wrong choice [going to China]?” [Ed. Note: Martial law was declared on May 19, 1989 to go into effect on May 20, 1989].

FU: Okay. As I said, Wuhan University, Wuhan Municipality and University had been chosen by the French and the Japanese too as a kind of center for whatever you want to call it, propaganda, educational efforts, or whatever. So, there was a building that housed the foreigners, and it was much, much better than the building that housed the Chinese guests. When the violence occurred-

CL&P: The violence, you mean up in Beijing on [the night of] June 3rd [into June 4th]?

FU: Yeah. In Beijing. Martial law was declared the 19th you said?

CL&P: They declared it on the 19th to go into effect the 20th.

FU: And they didn’t go in with the famous tanks until the 3rd or 4th, right?

Protestors in Beijing pushing back the army soon after martial law was declared on May 19, 1989.

CL&P: They started with tanks, but then the people in Beijing were able to push back the tanks after martial law was declared. Then the protests continued up in Beijing until the night of-

FU: And the killing occurred on the 3rd?

CL&P: Yes, June 3rd, the night of June 3rd, into June 4th.

FU: I think it was when the killing occurred. By that time all the Chinese visitors in the Chinese guesthouse had left, which of course they would. They wanted to go home. There was no class. There was no reason to be there, unless you were like me and you were interested in what was happening. So, I was living in the Chinese guesthouse by myself. I should have changed rooms then to get out of the way of the leaks, but I didn’t. Anyway, I got to know the people in the Chinese guesthouse. Then I got a request from the head foreigner or something to move to the foreign guesthouse. So, I thought, “I should do that.” That was the responsible thing to do. So, I moved for one night.

I had not been at all apprehensive about my personal safety up to that point. I moved in with the foreigners, and they were I think it’s fair to say, I’m not a doctor, but hysterical. They were convinced that the regime was gathering an army [in Wuhan]. And this may be true. The president of Wuhan University had been told to – this is all what I heard; I don’t know that any of this is true, remember – he had been told to go talk to the army, that the army was surrounding Wuhan University or preparing to come in; that they were waiting to get soldiers from outside of the region, so that on the theory that people from Guangzhou will happily slaughter people from Hubei, whereas people from Hubei will not. So that was the general zeitgeist of the people there [in the foreigners’ guesthouse] was that there was a chance all foreigners would be killed.

I laugh now. I laughed then. It was this ridiculous idea. But most of the people there, they were French literature specialists. There was a guy from Ohio State who was there teaching about American history. They didn’t know anything about China. I’d spent a fair amount of time in China – Taiwan, but I consider it the same culturally – so I was not scared until I moved into the foreign guesthouse. I knew intellectually I shouldn’t be scared, but I was hysterical. I got so hysterical that my mouth got dry. I started trembling. So, I spent one night in the foreign guesthouse and then I moved back to the Chinese guesthouse, and everything was fine. When the evacuation flight was organized, there were meetings among the foreigners, which were very interesting.

CL&P: Just to go back, how did you learn about the killings in Beijing?

FU: First place, it was over the VOA, and it was over the BBC. Some part of the dorms at Wuhan University at that time were on a slope, and they were low-rise kind of buildings. They were dormitories, but they weren’t big, huge, six story things. I would daily, I don’t know why, but I would walk up and back through these dormitories. You never stopped listening to the Voice of America or BBC because there were people listening to it the whole time.

CL&P: Were you able to observe the Chinese students’ and faculty’s reaction to what happened on June 3rd, June 4th, [the night of] the killings?

FU: Yes.

CL&P: What did you observe?

Wuhan University’s historic dorms – where VOA and BBC were playing non-stop in the spring of 1989.

FU: The way I knew that there were people going out on marches when I first got there was there would be marching music, there would be a kind of marching music. And the music had died down, because, as I said, the protests had died down. Then I guess it was a Sunday, the 4th, the music was up again. I don’t know whether I had already heard that there had been killings or not, but I heard the music. Maybe the people at the Chinese guesthouse told me about it. So, I went there. There were lots and lots of people there.

CL&P: So, the students were continuing to protest, even after learning-

FU: Well, they started again.

CL&P: They started again. Okay. Were you able to observe how long that lasted, how many-

FU: Well, it lasted until I left. Again, I was there. Of course, people were excited. I don’t mean like they were enthusiastic. I mean, it was a traumatic event, and they organized, and we marched, and we went to the same place. That was spontaneous, but then there was an organized march. I don’t know how I found out about that, but by that time I knew students. They undoubtedly told me that there was going to be not just the daily march, but a march in capital letters. That was one of the most awe-inspiring things I’ve ever witnessed.

CL&P: What made it awe-inspiring?

FU: Well, I was told about it, and so I went out early, before the march. I went to this 16 lane bridge or whatever it is, this place we were talking about. At the far end of the bridge was a kind of little hill. I knew by that time that that was a good place to watch the demonstrations. I went early on, and I went up on the hill, and I was by myself. Then I heard the music, but it wasn’t marching music or whatever the music had been before. It was funeral music. As I was watching, the marchers came from across the river, or rivers, or whatever. I should go back to Wuhan and look at this.

But they came. It was not a protest march. It was a funeral march. Everybody was in perfect alignment. Everybody was wearing, I can’t remember what, but I have a memory that they were wearing a particular kind of clothes. They were chanting things or singing things that I knew were mourning, were expressing mourning. They came across that bridge, and it was a sea of humanity. They came to the bottom of the hill, where I was, where they gathered. It was people from the bottom of the hill, where I was, filling every street, the whole bridge, across the river. It was just people. As far as I knew, I was the only non-Chinese there.

CL&P: So, how many days did this last, if you can remember?

FU: I can’t remember. There was that day, and then I think I don’t have any memory after that.

CL&P: Then when you were there observing it, did you see any police or any army coming around during this?

FU: No. I’m making all these authoritative statements without-

CL&P: Well, you don’t recall it precisely.

FU: Yeah. Okay. But anyway, my sense was throughout that there was nobody in Wuhan who did not sympathize with us.

Wuhan’s Yangtze River Bridge

CL&P: For you, when did you leave Wuhan, and how did you leave Wuhan?

FU: My wife and family. . . .This was 1989, so I had a 12 or 13 year old son and a six or seven year old daughter. They were watching this on American television. They were probably just as hysterical as I attribute to the people in the foreign guesthouse. I was in touch with my wife partially through the consulate in Shanghai. She wanted me to get out. I, of course, wanted to stay. But John Kerry was the senator from Massachusetts at the time I think, and he is a graduate of Boston College Law School, where I was teaching at the time. We should ask my wife about this, but I think my wife contacted Boston College Law School and said, “Would you get my husband out of there?” John Kerry got involved, I think. This is the way I remember it. There was an evacuation flight organized.

I think I was still living at the Chinese guesthouse at the time, but I was chosen, probably because the three nationalities that were there were English speaking people, which included a lot of people. And then there was a group of French speakers and a group of Japanese speakers, and I have some Japanese language and some French. I think that was one of the reasons I was chosen as one of the two organizers for the evacuation flight. I’m trying to make this as accurate as possible. I was asked, along with the other person – and I can visualize her, but I can’t remember her name, she was also a lawyer – we were asked to literally decide who was going to get on the flight and who wasn’t.

CL&P: Oh, God.

FU: By this time, however, I wanted out. And I wanted out because it went from being exciting – although it was exciting in a kind of perverse, vicarious way of seeing people suffering – to being profoundly depressing, because that was the overall emotion that people I knew at Wuhan, not just the University, but elsewhere. It was one of just not sorrow, depression. And depression is deadening. There’s just nothing to exist for. I wanted out at that point because there was no reason to stay. Nothing was happening. There wasn’t anger. It was just there’d been such incredible hope, and enthusiasm, and passion, and now it was just. . .over.

So, we had this evacuation. Oh, yeah. We were trying to get out. The consulate in Shanghai, we were calling someone at the consulate in Shanghai, because this other person, this lawyer, she and I were sort of trying to organize this kind of stuff. The person at the US consulate said to me, “Well, you’re on the Yangtze River, aren’t you?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “Well, why don’t you just get on a river boat?” I said, “I’m not sure that’s going to work.” He said, “Well, I know. Why don’t you commandeer a bus and drive to Shanghai?” I was just in wonderment at that. There’s no Second Amendment. I wasn’t armed. I didn’t know exactly how I was going to commandeer a bus. Later I found out that that guy who was talking to me at the consulate had arrived a month before. He knew nothing. He was just somebody who was sent around the world, and he handled troubles. He knew nothing about China. After that, we got the evacuation flight.

Tanks on Tiananmen Square in Beijing, after the crackdown where the government killed anywhere from hundreds to thousands of peaceful protestors.

CL&P: Then you went home on the flight?

FU: Yeah. Went to Hong Kong on the flight and then home.

CL&P: Oh. Hong Kong and then home. I guess looking back on it, from 30 years ago, I mean, you went because you wanted to witness history.

FU: Well, I went originally because I wanted to brush up my Chinese.

CL&P: Right. But the decision you made after the advice from Professor Cohen was to see history. I guess in being a witness to that history, has it impacted your life at all? What do you think about when June 4th comes around every year? Do you think about what you experienced, or has it played any role in where you’ve gone in life or how you view the world even?

FU: [Long Pause] Clearly, it’s a question I don’t have a ready answer for. I resist this response, but I think my response is “no.” I was in Vietnam during the war, so that was witnessing history. I mean, did it make me more sympathetic to the Chinese democracy movement? Did it make me more sympathetic to public protests generally? Did it make me want to throw myself into human rights in China, that kind of thing? I don’t think so. It certainly deepened my emotional involvement with China, but I don’t see it. . . .I went along to the parent-teacher conferences after I got back to Massachusetts, just like I had before. It didn’t change the pattern of my life in any way I can identify.

If Jerry had said, “Don’t go,” I wouldn’t have gone. But if Jerry hadn’t been there, I don’t know what I would have done. But I’m very, very glad I went, because it’s a major part of what I remember about what’s made my life. . . .It was an encounter with raw emotion on a mass scale, seeing people dedicated to something. It was inspiring, but I didn’t head to the barricades when I got back to Newton [Massachusetts].

CL&P: Contrasting the inspiration you saw from the people, what about the impact of the government’s response to the protests? I mean, has that. . . .and the ability of people to affect change in an authoritarian regime through protest-

FU: Above my pay grade. I would say that if you want to affect change, you occupy illegally someplace, and they shoot you, it’s probably discouraging. But political change continued to occur in China. I’m not an expert on the politics, or human rights, or democracy in China, but I follow it. I follow the legal side, mainly property rights. But until President Xi sort of, not sort of, but turned against any kind of participatory democracy, if not electoral democracy, I didn’t see the intervention in the [Tiananmen] Square as just stopping everything cold. It continued. I had lived in Taiwan for two years when it was a police state, just like China. I had my room searched. There were spies in my classes. I was teaching English.

Taiwan, a vibrant democracy that can commemorate the bravery of the lives lost on June 4, 1989.

And then I observed Taiwan becoming this vibrant democracy. That’s what I expected China to be. Stupidly, I looked at Taiwan. I looked at Korea. I looked at Japan. Japan was a democracy before World War II for a while. I just want to make that clear. America didn’t make Japan a democracy. It made itself a democracy. I thought, “Well, that’ll happen in China too.” Maybe not. I don’t blame Deng Xiaoping for that so much as I do Xi, to the extent I blame anybody. I don’t know where the Tiananmen killings figure into that, but I don’t think they were the thing that changed China, but I don’t know. Obviously, I’m not a political scientist of China.

CL&P: All right. Well, I want to thank you, Frank, for sitting down with us and just reliving your experiences from 30 years ago. I know it was to the best of your recollection, so we won’t hold you to the facts.

FU: Yes. Thank you, Elizabeth. I just want to make sure that. . . .I tried to qualify it probably too many times, but. . . .I have a student now, a PhD student, she’s not directly my student, but she’s a friend of mine. I told her about this interview. It was going to be yesterday, and so she was going to come. I mean, she was here at 4:00, and she was going to stay, because she said she didn’t know about the Tiananmen incident until she came to the US.

I think it says a couple of things. It’s a long time ago. It’s not a long time ago for me. But she wasn’t born then. And it also talks about the way information can be shaped in China or in any other place.

CL&P: All right. Well, thank you, Frank.

FU: Thank you, Elizabeth. It was fun.

***********************************************************************************************************************

Please join us next week, as China Law & Policy continues its series “#Tiananmen30 – Eyewitnesses to History” and sits down with noted Chinese human rights lawyer, Teng Biao. Learn about the political indoctrination Teng Biao experienced as a high school student in rural Jilin back in 1989.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

[…] Beijing. Michigan Congressman Andy Levin, who was in Chengdu as a student, wrote about what he saw. China Law and Policy blog interviews NYU law professor Frank Upham about his experiences in Wuhan, and Andréa Worden about hers in Changsha, in the spring of […]