Book Review: Leftover Women – The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China

|

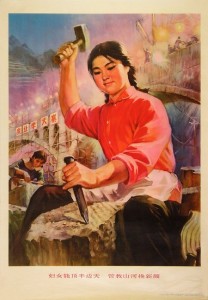

For over 60 years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has promoted itself as a champion of women’s rights. It was Mao Zedong who famously proclaimed “women hold up half the sky.” In making such proclamations, the CCP has crafted the story that in Asia, an otherwise bastion of patriarchal societies, China is an oasis of women equality.

But Leta Hong Fincher, in her new book Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China, unmasks that myth and exposes a disturbing, shocking and ultimately depressing development: China likely has one of the fastest-growing gender wealth gaps in the world. And the culprit of that increasing inequality? The Chinese government itself.

As Fincher convincingly demonstrates, it all starts with the concept of a “leftover woman,” a recently-developed ideology splashed not just all over the government-run newspapers but promoted

by government agencies like the All-China Women’s Federation, an organization ostensibly designed to encourage female empowerment. Basically, if a woman is not married by 27, she is labeled a “leftover woman.” The older one gets, the worse the mind games become, mind games that are played out in the press and on TV on an almost daily basis. As a result, women, especially educated women who are mocked even more vigorously, feel societal pressure to marry at a young age; if you are leftover, no one will want you. But, as Fincher shows, this fear is utterly illogical. Due to the preference for boys in what has been one-child country for the past 30 years, China has a shortage of marriageable women. Not to mention, if you can only have one child, what is the rush in getting married? But in perhaps one of the most shocking parts of the book, doctors – licensed medical professionals – lie to their female patients, instilling fear in them that babies will be born with birth defects if conceived after the age of 30.

In Leftover Women, Fincher shows that this fear of being leftover has resulted in women being left out; left out of one of the largest gains in individual wealth in Chinese history: property accumulation. To understand better the connection between the two, Fincher set up a Weibo (Chinese version of Twitter) account to survey hundreds of young Chinese women. Through revealing snippets of interviews with these 20-somethings, it becomes clear that this fear of being leftover by the age of 27 has taken hold in the women themselves. This fear causes women not just to rush into a marriage but act against their own economic self-interest. Many of these well-educated, well-employed women will provide cash toward the down payment on a marital home without putting their name on the deed. Instead, as Fincher documents, in the vast majority of apartments occupied by married couples, only the man’s name is on the deed due to the resurgence of traditional gender roles. Shockingly many of the women interviewed accept these roles, acknowledging that they are effectively being swindled, but hint that it is all worth it so that they are not “leftover.”

Changes to the Marriage Law in 2011 only further perpetuated these non-progressive gender norms. In 2011, the Supreme People’s Court issued an interpretation of the Marriage Law finding that in the case of the divorce, the property goes only to those whose names are on the deed unless the other party can clearly show their monetary contribution. But because down payments are in cash, receipts are often not kept. Further, China does not allow joint bank accounts and it is usually the husband who writes the monthly mortgage check, even if the wife is providing cash contribution or providing for other household needs such as food and childcare. But under the new interpretation, these contributions are not considered. So, yes the interpretation is neutral on its face, but its disparate impact it clear. This is an interpretation that is going to screw women.

Rushing into marriage and losing their economic independence leaves these women vulnerable to another increasing and alarming practice in China: domestic violence. Through the interviews that Fisher conducted, a general trend emerges: these women will often stay in an abusive marriage because otherwise they will lose everything. Not to mention that the Chinese government, even after years of lobbying, has yet to adopt a Domestic Violence law. As a result, the police’s treatment of domestic violence is anything less than sensitive and is usually just seen a family matter for the wife and her abuser to handle on their own.

Leftover Women is a chilling portrayal – often told through the voices of the women themselves – of the rapid deterioration of women’s equality in China. If you think you know China, you don’t until you have read this book. It exposes an ugly development where, through pressure to marry young, the resurgence of traditional gender norms and laws that promote male property ownership, the Chinese government is keeping women out of the property market and thus out of an important segment of societal wealth.

Unfortunately, China is not alone in keeping a group of people out of property ownership and thus wealth accumulation. In an essay that was published in June in the Atlantic, Ta-Nahesi Coates illustrates the racist policies of home ownership in the United States that has largely kept communities of color out of one of America’s most important sources of family wealth. The initial culprit? The U.S. government itself. Reading these two pieces together will make you doubly angry, but also more reflective on how wealth is accumulated in any society and the desires to keep certain groups of people out.

Rating:

Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China, by Leta Hong Fincher (Zed Books 2014), 192 pages.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email