A Rose By Any Other Name….. Violence & Repression Under Xi Jinping

For Tang Jitian (pronounced Tang Jee tee-an), a human rights advocate and disbarred criminal defense lawyer, 2013 should have been a banner year. The new Criminal Procedure law took effect ostensibly providing for greater rights for defendants and their lawyers; the Supreme People’s Court’s new President, Zhou Qiang, highlighted the pressing need for the judiciary to respect criminal defense attorneys; and the Third Plenum of the Party’s Central Committee released its resolution, calling on the Party to “give rein to the important function of lawyers in safeguarding citizens’ and legal persons’ lawful rights and interests.” To cap it all off, in December, the government abolished the much reviled Re-Education Through Labor (“RETL”), an administrative punishment unsupervised by the court system that often resulted in hard labor sentence of up to three years.

For Tang Jitian (pronounced Tang Jee tee-an), a human rights advocate and disbarred criminal defense lawyer, 2013 should have been a banner year. The new Criminal Procedure law took effect ostensibly providing for greater rights for defendants and their lawyers; the Supreme People’s Court’s new President, Zhou Qiang, highlighted the pressing need for the judiciary to respect criminal defense attorneys; and the Third Plenum of the Party’s Central Committee released its resolution, calling on the Party to “give rein to the important function of lawyers in safeguarding citizens’ and legal persons’ lawful rights and interests.” To cap it all off, in December, the government abolished the much reviled Re-Education Through Labor (“RETL”), an administrative punishment unsupervised by the court system that often resulted in hard labor sentence of up to three years.

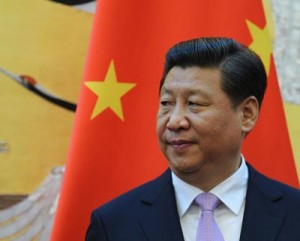

But for Tang Jitian, 2013 and the early months of 2014 have proven to be anything but positive. Instead, human rights advocates have experienced one of the worst years since 2008 according to the 2013 Annual Report published by the non-profit Chinese Human Rights Defenders (“CHRD”). Under the leadership of China’s new president, Xi Jinping (pronounced See Gin ping), there have been more than 220 criminal detentions of human rights defenders, as documented by CHRD’s report, a three-fold increase from the previous year. The number of detentions that have not gone through the legal process if even greater.

What makes Xi’s crackdown different – and more ominous – than previous ones is its veneer of legality and its attempt to mask the increased levels of violence.

Nothing exemplifies that better than what happened to Tang Jitian in China’s Heilongjiang province this past March.

Whac-A-Mole: RETL is Replaced By Other Administrative Detention

As a human rights attorney, Tang has represented some of China’s most vulnerable, in particular adherents of the spiritual movement Falun Gong. The Chinese government has categorized Falun Gong as a cult not necessarily as a result of any of its practices, but rather as an easy way to target a movement that was able to amass a large number of dedicated followers in a short amount of time. It was Tang’s zealous advocacy of a Falun Gong practitioner that led to his disbarment in 2010.

On some level, one cannot be a human rights lawyer in China without understanding the particular plight of Falun Gong practitioners. And that is why Tang ended up outside of a Jiansanjiang (pronounced Gee-en san jee-ang) detention Center where several Falun Gong practitioners were being detained in a “Legal Education Center.”

While the Chinese government may have eliminated the RETL system, it did not get rid of all forms of administrative punishment. In its place popped up drug rehabilitation centers to house many of RETL’s drug addicts and legal education centers to deal with RETL’s Falun Gong practitioners as well as citizen petitioners, people the government has deemed “troublemakers.” The ability to detain individuals without proper legal procedures has been too powerful of a tool for a government with an obscene infatuation with “social stability” to give it up so easily. For these detained individuals, it is of little consolation if the prison they find themselves in is called a labor camp or a legal education center. In the end they are still deprived of their liberty without any legal review or access to lawyers and often with little to no contact with their families.

When the Lawyers Become the Victims

It was this discrepancy that Tang and three other human rights lawyers – Jiang Tianyong, Wang Cheng and Zhang Junjie (the Jiansanjiang Four) – sought to bring attention to by trying to serve as attorneys to the Falun Gong practitioners being held at the Jiansanjiang Legal Education Center. However, before the Jiansanjiang Four could lodge formal complaints on behalf of their clients, the police raided their hotel room and detained the four attorneys.

Zhang Junjie would be released five days later; Tang Jitian and Jiang Tianyong were held in detention for 15 days. None ever went

before a judge but again the law allows for this form of administrative punishment as well. In March 2006, China’s Public Security Administrative Punishment Law (“Admin Punishment Law”) – a law that gives free rein to the police to detain individuals for up to 15 days – went into effect. Under the law, the police essentially serve as prosecutor, judge and jury. Although there is an appeal process, as Joshua Rosenzweig notes, “it’s possible to request that a detention be postponed pending the outcome of such a challenge [appeal], but, again, police have discretion to decide this based on whether they think the individual will continue to be a harm to society. So, basically one has little option but to serve one’s time in jail first and pursue remedies later.”

Each of the Jiansanjiang Four were held under the Admin Punishment Law. Tang and Jiang were given the maximum punishment of 15 days for “using cult activities to endanger society.” It was Tang and Jiang’s attempts to represent Falun Gong practitioners – the very reason for their profession and protected by the Lawyers Law – that was punished.

Under the Veneer of Legality, Increase Levels of Violence

Five to 15 days might not seem like a long time, but for someone being tortured, it is an eternity. While being held by police, each of the Jiansanjiang Four experienced repeated beatings and each needed to go to the hospital upon their release. This is what makes the Admin Punishment Law dangerous – without any supervision or the ability to appeal the sanction, the police have free rein to do what they want with these “troublesome” human rights advocates.

This type of violence against human rights advocates is becoming increasingly common under President Xi Jinping. While beatings are the most common, denial of services, including food and medical treatment has also become prevalent and at times with dire consequences. Tang Jitian suffers from spinal tuberculosis. According to Boxun, while at a Beijing hospital after his detention, Tang was initially informed that surgery was necessary to avoid paralysis. But a few days later, the head of the hospital visited Tang’s room to inform him that the surgery was not possible at the hospital and suggested that he leave. Tang’s TB, at least the spinal portion, is going untreated.

For Cao Shunli, another human rights advocate who had been criminally detained since September 2013, it was her medical condition mixed with possible beatings that eventually killed her. On March 14, 2014, while still in police custody, Cao died of as a result of her tuberculosis. Her family claims that her TB was left untreated and that she was physically abused in police custody. To this day, Cao’s body has not be release to her family for proper burial.

But while China conducts one of its worst crackdowns on human rights advocates, it is still able to obtain a seat on the United Nations’ Human Rights Council, a body responsible for enforcing many of the international human rights standards which the Chinese government violates with abandon. One wonders how many other human rights advocates must die before the world wakes up.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email