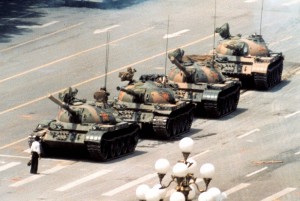

How to Remember a Past – 24 Years Since Tiananmen

Twenty-five years is a silver anniversary; fifty a golden and seventy-five, a diamond jubilee. But 24 years? There is nothing in particular to mark a 24th anniversary – no special color, no special symbol, little attention in the press.

Twenty-five years is a silver anniversary; fifty a golden and seventy-five, a diamond jubilee. But 24 years? There is nothing in particular to mark a 24th anniversary – no special color, no special symbol, little attention in the press.

On Tuesday, the world will mark this nondescript 24th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. The 20 year old idealistic college students who called for greater equality and believed in their government back in 1989, those kids will turn 44. The parents who had to bring home a dead son or daughter, they will have to face another lonely anniversary of remembering.

But their remembrance will be in silence. The Chinese government does not mark the passing of its violent crackdown on thousands of unarmed, college students on the night of June 3, 1989 and doesn’t allow its state-controlled press or its people to do so either. The American author William Faulkner once wrote “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” But in China, that’s just not true of the Tiananmen Square massacre. Since 1989, the Chinese government has effectively expunged the events of that night from society’s collective memory, especially among the young. Today, it is not uncommon to find college students – students the same age as those killed in 1989 – who know little or nothing of the event, who have never heard of the “Goddess of Democracy,” and have no clue about the bravery of their countrymen in attempting to form a more perfect country.

Unfortunately, the Tiananmen Square massacre is not the only part of China’s past that has been forgotten. Take the Cultural Revolution. From

1966 to 1976, China, at the behest of Mao Zedong, descended into chaos. Various factions of high school and college age Red Guards were in charge, parents, teachers and intellectuals were publicly ridiculed, some tortured and the unfortunate ones killed.

Today’s youth do know about the Cultural Revolution but only the white-washed version. Walk into any hip shop on the cute street of Nanluoguxiang in Beijing and it will be filled with kitsch Cultural Revolution memorabilia. Red Guard hats and armbands, t-shirts with puns of popular Cultural Revolution slogans on them, Mao wristwatches. All of these are bought with gusto by Beijing’s youth. But while certain aspects of the Cultural Revolution are allowed to be discussed, the seamier parts – the hundreds to thousands of people killed (either by their own hand or by overzealous Red Guards) and a generation of dreams shattered because of insane policies of the government – are largely unknown to the young.

Every society and every culture has parts of its past it would prefer not to remember. The United States, with its sordid treatment of various ethnic groups throughout its history, is no stranger to forgetfulness. The 1862 mass execution of 38 Dakota Indian men for war crimes is known by very few. In fact the specifics of our treatment of Native Americans is rarely taught in school. It’s not uncommon for a high school lessons on the United States’ treatment of Native Americans to – sadly – be concluded with a showing of Dances with Wolves.

Although historical forgetfulness is never good, there is a difference between a people deciding to forget their past and a government that gives their people no choice. A people should be allowed to acknowledge those actions it deems significant to its culture. For the United States, many of the marches, protests, and bravery of ordinary Americans during the civil rights movement have come to be celebrated, even those events that at the time that seemed pernicious.

But for China, the people have not been given that opportunity. The Chinese people have not been allowed to celebrate their fellow countrymen and women who, during one spring season believed in a better country and who in one night lost their lives at the hands of their own government.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

Reading your comment, it makes one think that a truth and reconciliation commission would start to heal the wounds, but there is so much distrust that a sudden attempt at honesty would only make things worse. Ironically, the main complaint of the Chinese against Japan (fishing rocks excluded) is that they refuse to include their WWII atrocities in textbooks, without even knowing that they themselves are victims of the same outrage.