Book Review – The Corpse Walker: Real Life Stories, China from the Bottom Up

Too often Westerners’ views of China are shaped through the eyes of a select few – Ai Weiwei, Han Han, and in the legal world, He Weifang, Xu Zhiyong, and Chen Guangcheng. How they see China is often how we see it. China is far from an open society and these individuals are educated, media savvy, and maintain a good rapport with foreign reporters. Make no mistake, they have important stories to tell.

But it is rare to know what the average Chinese person thinks and feels about his own history; what is important and what shouldn’t be forgotten. Although China has a history that spans more than 2,000 years, it doesn’t have the same respect for the individual history and experiences of the everyman. There is no Library of Congress that attempts to collect the stories of former slaves before they die or a StoryCorps project where anyone can go to a recording booth and interview a friend or family member. In some ways, there are likely stories that the Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”) would rather forget.

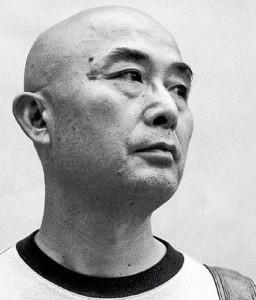

Fortunately for China and for us, there is LIAO Yiwu and The Corpse Walker: Real Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up. In his way, Liao Yiwu is trying to be the Library of Congress, interviewing average people before their histories are forgotten. In The Corpse Walker, 27 of Liao’s interviews with average Chinese people are translated into English, giving the reader a more democratic view of China.

Three of the first four of Liao’s interviews – The Professional Mourner, The Public Restroom Manager, and The Corpse Walkers – paint a picture of a China that is long gone. But Liao is able to capture these dying professions and the men who filled them. And while they tell the stories of China’s past, their stories are still familiar. The public restroom manager is still bitter from an incident with a young punk who teases him because of his work, but ultimately he is just happy to have a job. The corpse walker discussing how to “walk a corpse” and tells his story with the nostalgia of an old man thinking back to other times.

But in each of the 27 interviews, not a single person has been left unscathed by the CCP’s various campaigns and politics. Liao doesn’t have to delve deep to get these stories. For each person, the Land Reform Movement, Great Leap Forward, the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Cultural Revolution, or the Tiananmen crackdown, have shaped their lives.

It is particularly poignant in The Yi District Chief’s Wife. The wife – Zhang Meizhi – and her family did not fare well during the Land Reform Campaign. As members of the highest caste of the Yi minority, a caste-based ethnic group in southwest China with land being owned primarily by the highest caste, Zhang and her family were major targets of the Land Reform. After witnessing her husband’s execution and the subsequent cutting of his tongue from his mouth, Zhang’s struggle was far from over. Her eldest son became a target, forcing him to live in a hole in a ground for years to avoid the same fate as his father, all the while degenerating into a wild existence. Today, Zheng has not forgotten; she has forgiven to a degree, but she has not forgotten. Unfortunately, as she points out, the children of those who want to forget already have.

In The Retired Official, Liao interviews Zheng Dajun, an official who headed a government work team in rural Sichuan during the Great Leap

Forward. Zheng eye-witnessed a country descending into one of the worst famines in modern history and a people spiraling to a state of nature in the rural areas. Slowly the starving people moved from eating white clay and drinking castor oil to cannibalism. Although Zheng repeatedly informed higher officials, nothing was done to stop the export of needed grain from the rural areas to the cities.

Perhaps the most moving of all of Liao’s interviews is The Tiananmen Father. As poor workers in Sichuan province, Wu Dingfu and his wife felt lucky that one of their sons excelled in school; both were ecstatic when their son passed the college entrance exam and attended college in Beijing. Wu tells the story of his son, a young man who believed in something and then like many college students, got in over his head. But before he could get out, he was killed by the troops on their way to Tiananmen Square. In Wu’s interview, you can feel not just the ache of a father bringing not just his son’s body back to Sichuan, but the collapse of a dream that his family could do better.

The Corpse Walker is an important read since the voices of China’s average person are finally heard. And what’s remarkable is that while their stories are different from ours, the emotions are not: the bitterness of working a menial job; the need to forgive to go on living; the anger of a former government official who tried to do the right thing; the emptiness of a father who has to bury his son. If just for this reason – for showing the humanity of the average Chinese person – The Corpse Walker

is an important read.

But The Corpse Walkeris vital as a depository of China’s history, the history that the people – not the Party – wants to tell. The Chinese Communist Party is in denial of its past; it does not want to recognize the divisions and violence that has been a result of its rule and it hopes

that China’s economic miracle can serve as bread and circuses for the young, causing them not to even ask about the past. But as Liao makes clear in some of his more prescient interviews, the past is often the catalyst for the future. Can it be forgotten or more importantly, should it be? For Liao, the answer is no, but for the rest of China, the answer is much less clear.

Not all of Liao’s interviews are as remarkable as the ones mentioned here. Some are boring and at times, Liao can be rather didactic in his questioning of those that he has less sympathy for which detracts from the stories he is trying to tell. But the interviews mentioned here, especially The Tiananmen Father, must be read. Because to understand China’s present, we must understand how the victims of China’s past live today.

Rating:

The Corpse Walker, by Liao Yiwu (Anchor 2009), 352 pages.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email