A Paper Tiger? China Issues New Regulations to Exclude Illegally Obtained Evidence

It is rare to wake up in the morning, turn on the computer and find that China just made huge changes to its criminal procedures, and in a positive way. But that was exactly where I found myself Tuesday morning when I saw that China passed two new criminal justice regulations, one of which attempts to stem the tide of the increasing use of confessions obtained through torture.

Torture of criminal suspects in order to obtain a confession remains a common practice in China as the confession is usually the key piece of evidence in criminal trials. But as a signatory to the United Nations’ Convention Against Torture, such action is nominally illegal in China. Article 43 of China’s Criminal Procedure Law (“CPL”), forbids the use of torture or coercion in obtaining statements or evidence and in the Supreme People’s Court’s Interpretation of the CPL (“SPC Interpretation”) – a document meant to provide greater detail to the vaguely drafted CPL – Article 61 states that evidence obtained through torture cannot be used as the verdict’s basis.

But neither of these provisions directly discusses the actual admissibility of this illegally obtained evidence, and the SPC Interpretation is only applicable to judicial bodies, not administrative organs such as the police or the state security bureaus. Because current law is silent on its admissibility, confessions obtain through torture, while nominally illegal, are routinely used in criminal cases. And the danger associated with such methods, namely the risk of sentencing an innocent person to prison or even death, have been increasing. Just this month, Henan farmer Zhao Zuohai was released from his 11-year prison sentence when the man he was found guilty of killing, returned alive to their village.

Zhao’s story is not a one-off event, and such occurrences usually receive a tremendous amount of media attention, causing the Chinese public to be critical of the criminal justice system, question its validity, and, as a result, frighten the Chinese government. There have been rumors of reform for the past few years, and on Monday morning such reforms were adopted. The SPC, the Supreme People’ Procuratorate (SPP), the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), the Ministry of State Security (MSS), and the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) released two new regulations: “Regulations on Examining and Evaluation Evidence in Capital Cases” and “Regulations on the Exclusion of Illegally Obtained Evidence in Criminal Cases.” The Regulations on the Exclusion of Illegally Obtained Evidence goes the furthest in providing greater protection of criminal suspects and, through various procedural safeguards, attempts to eliminate the use of torture in obtaining confessions.

The reforms, which seem to be taken directly from a Law & Order episode, are rather sweeping and sophisticated, and

if implemented, can successfully eliminate torture and provide for greater justice. But that’s the catch: in a system where more than 70% of defendants go without counsel and in the few cases with counsel, obstacles to effective representation abound, will such reforms really mean anything? Because the regulations have yet to be publically published, the analysis below is based upon a summary provided to the Chinese media by Prof. Fan Chongyi, noted criminal law professor at the China University of Politics and Law and participant in drafting the reforms.

(1) Oral testimony that is the result of torture may be excluded from evidence. Oral testimony that was the result of improper procedures, such as when only one investigator partakes in an interrogation [the law requires at least two interrogators], does not necessarily have to be excluded if it can be corrected.

Although this regulation certainly clarifies that courts may exclude confessions obtained through torture, the new regulation in no way creates an absolute “exclusionary rule.” Instead, by using the term “may,” the regulation largely leaves it in the hands of the courts to decide whether to admit evidence obtained through torture. Given the lack of judicial independence and the power of local security bureaus in China, it is questionable if local courts, when pressed by more powerful forces, will in fact exclude confessions based on torture. Additionally, in cases where improper procedure was used, it is unclear what would need to be done to “correct” the issue and allow for the testimony to be admissible. Perhaps the regulations, when officially issued, will clarify this.

(2) The defendant and his attorney have the right to request a pre-trial hearing concerning an illegally obtained confession. The court may request that the defendant or his lawyer provide the names of the alleged officer involved in the illegality, the place, the time, the method used, the content of the illegality, and anything else related to the claim.

In a society with few rights for defendants, this regulation explicitly providing for the right to raise the issue of admissibility is rather extraordinary. Additionally, the regulation calls for a pre-trial hearing to determine whether illegally obtained evidence should be admitted. By separating the decision concerning the admissibility of the evidence from the actual trial, the regulation attempts to guarantee that the illegally obtained evidence in no way influences the final verdict.

By giving the defendant the right to question the admissibility of evidence, the regulation raises a bigger issue: when most defendants are not represented by counsel, who will inform the defendant of his or her rights? Presumably in a situation of a confession obtained through torture, neither the police nor the prosecutor has much interest in informing the defendant of his right to attempt to invalidate the confession they just worked hard to obtain. The alternative, that the court informs the defendant of his or her right, does not appear to be mandated by the regulations, making it questionable if the court will, on its own initiative, inform the defendant. Given the pressures on the court as discussed in point 1 above, such action appears unlikely.

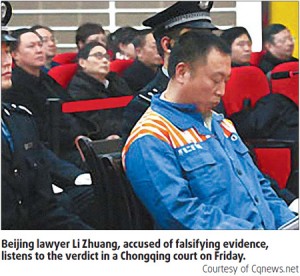

But even with a lawyer, a defendant will still have difficulty in raising the issue of a coerced confession. A  defendant’s changing his testimony, even if the prior confession was in fact the result of torture, is not in the self-interest of his attorney. Article 306 of China’s Criminal Law (CL) provides criminal liability, and a prison term of up to seven years, to lawyers who entice their clients to change their testimony in opposition to the facts or to give false testimony. While the overarching purpose of the sanction – to ensure that lawyers do not encourage their clients to lie – is laudable, Article 306 has been used by police and prosecutor as a way to intimidate defense counsel from questioning the validity of any confession, even when torture is obvious. And this is not an idle threat. This past year, after a high-profile case representing an organized crime syndicate in Chongqing, criminal defense attorney Li Zhuang was charged with violating Article 306 by advising his client to recant his confession on the basis that it was obtained through torture. Li was eventually found guilty and sentenced to one year and six months in prison. Thus, as long as there is Article 306, there remains an incentive for lawyers to advise their clients NOT to recant their confession.

defendant’s changing his testimony, even if the prior confession was in fact the result of torture, is not in the self-interest of his attorney. Article 306 of China’s Criminal Law (CL) provides criminal liability, and a prison term of up to seven years, to lawyers who entice their clients to change their testimony in opposition to the facts or to give false testimony. While the overarching purpose of the sanction – to ensure that lawyers do not encourage their clients to lie – is laudable, Article 306 has been used by police and prosecutor as a way to intimidate defense counsel from questioning the validity of any confession, even when torture is obvious. And this is not an idle threat. This past year, after a high-profile case representing an organized crime syndicate in Chongqing, criminal defense attorney Li Zhuang was charged with violating Article 306 by advising his client to recant his confession on the basis that it was obtained through torture. Li was eventually found guilty and sentenced to one year and six months in prison. Thus, as long as there is Article 306, there remains an incentive for lawyers to advise their clients NOT to recant their confession.

Finally, while the regulation’s designation of a pre-trial hearing to determine the admissibility of illegally obtained evidence is a step in the right direction, such a pre-trial hearing is meaningless if the judge deciding the admissibility of the evidence is the same judge that will determine the guilt or innocence of the defendant (in China, judges determine guilt; there are no juries). Having the same judge decide both would defeat the purpose of attempting to prevent illegally obtained evidence from influencing the trial portion. It will be interesting to see if the officially published regulations will clarify this issue.

(3) After the defendant or his lawyer raises the issue of illegally obtained evidence and provides the details required by the court [see point 2 above], the burden of proof then switches to the prosecutor to show that the evidence was obtained legally.

This regulation is perhaps the most impressive in that it is also the most sophisticated. Burdens of proof are

difficult concepts to understand, and knowing when to switch the burden from one party to another, can give an otherwise ineffective rule teeth. The law seeks to switch the burden of proof to the party that has the greatest opportunity to determine the truth. Here, as China correctly notes, that party is the prosecutor. The prosecutor, in working with the police and at times as part of the interrogation, has the best opportunity to demonstrate the admissibility of the confession.

Additionally, switching the burden of proof can also create an entirely new incentive structure to prevent the illegal behavior from ever occurring. Here, China utilizes this concept. Once the prosecutor has the burden of proof to show that evidence was obtained legally, he or she will seek to have procedures in place to guarantee that the police do not violate the law in obtaining evidence so that if the defendant raises the issue, the prosecutor can win. For example, while there has been a few cities in China that have experimented with videotaping police interrogations, this practice has largely remained isolated. But, with the switched burden of proof, prosecutors all across China will seek to implement methods to guarantee that confessions are obtained legally, and may seek to pressure their police counterparts to begin recording all interrogations. This regulation could potentially change the way interrogations are performed and recorded, reducing the risk that torture is used.

However, it is still subject to the criticism noted in points 1 and 2 above: will the court decide to exclude evidence even if illegally-obtained since it is not required to do so and will the defendant even know to act upon his or her rights? If the answer is no, then the incentives created by the switched burden of proof remain irrelevant.

(4) The interrogator (usually the police or the prosecutor) must appear in court and testify.

While this might seem mundane to most Americans, as Prof. Fan notes, for China, this is pioneering. In China,  there is very little live testimony during criminal trials. Just forcing someone to actually appear and testify in court is radical. Having that person be a police officer is even more shocking. In China, the state security apparatus is a powerful body and far outranks the courts or the nascent criminal defense bar. The fact that the MSS and the MPS agreed to this regulation is certainly surprising and raises a red flag: has the MSS and MPS really agreed to give the courts power over their employees?

there is very little live testimony during criminal trials. Just forcing someone to actually appear and testify in court is radical. Having that person be a police officer is even more shocking. In China, the state security apparatus is a powerful body and far outranks the courts or the nascent criminal defense bar. The fact that the MSS and the MPS agreed to this regulation is certainly surprising and raises a red flag: has the MSS and MPS really agreed to give the courts power over their employees?

Again, the criticism of the new regulations noted in point 1 and 2 are applicable here as well. Will we even reach the point that there is a hearing questioning the legality of evidence? Likely not. But regardless of those issues, the regulation itself seems to be without any bite. Unless the officially published version expounds upon this regulation, there are no procedures in place to determine which party can call the police office to testify or whether defense counsel will be permitted to cross-examine the police officer, both necessary to guarantee that the regulation is effective.

(5) In regards to illegally obtained physical evidence, if the illegally obtained evidence has the potential to influence the fairness of the trial, then it should be excluded unless there is a reasonable reason for the illegality or it can be corrected.

This regulation is perhaps the vaguest, and thus weakest of them all; it appears to be inspired by the U.S.’ “fruit of  the poisonous tree” (FPT) doctrine. Under the FPT doctrine, other evidence discovered as a result of an illegal search or interrogation is also excluded. For instance, after an illegal search of a house (the poisonous tree) a key to a locker is found and in that locker is the murder weapon (fruit), that murder weapon will also be excluded. An exception exists if it can be shows that the discovery would have been inevitable or the discovery would have been made through an untainted source.

the poisonous tree” (FPT) doctrine. Under the FPT doctrine, other evidence discovered as a result of an illegal search or interrogation is also excluded. For instance, after an illegal search of a house (the poisonous tree) a key to a locker is found and in that locker is the murder weapon (fruit), that murder weapon will also be excluded. An exception exists if it can be shows that the discovery would have been inevitable or the discovery would have been made through an untainted source.

China’s regulation here seems to adopt the spirit but not the substance of the FPT doctrine, by only looking to the FPT exceptions. In the U.S., the exceptions to the FPT doctrine are only applied to the fruit; no exception is made for the poisonous tree. Here, China applies similar exceptions to the actual tree, to the evidence that was obtained directly as a result of the illegal violation.

This regulation is further weakened by the fact that these terms “reasonable reason” and “corrected” are left completely undefined. Courts are left to their own devices to determine what these terms mean, a situation that was suppose to be avoided by these new regulations.

China’s “Regulations on the Exclusion of Illegally Obtained Evidence in Criminal Cases” is impressive and provides the architecture necessary to guarantee greater fairness in China’s criminal trials by excluding evidence obtained illegally. The sophistication of some aspects of the new regulations reflects China’s increasing understanding of the need for effective procedures in order to give meaning to its legal principles. However, these regulations should be viewed as a step toward greater progress; China has only stuck its foot in the water; it has yet to jump fully in. China needs to find solutions to the systemic problems plaguing its criminal justice system. Unless China makes efforts to foster a vibrant criminal defense bar, provide access to attorneys early in criminal investigations, and takes steps to create a judiciary independent from the state security and Party apparatus, the new regulations will likely have little impact in the short-term.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email