Book Review – Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultural Revolution

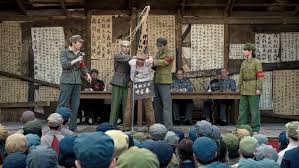

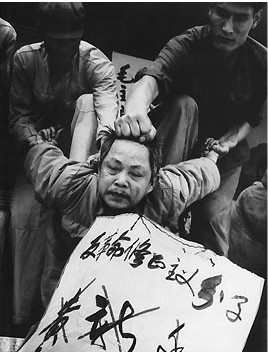

Netflix’s Three Body Problem opens with the worst of China’s past. As the camera pans over a group of fanatical youths, chanting and saluting with Mao Zedong’s little red book, it eventually settles on an old man atop the stage. Bloodied and on his knees, his arms are pulled behind him, held taught by angry Red Guards. A tall, paper dunce cap sits atop his balding head. Around his neck, hanging from a sharp metal wire, is a placard that labels him a reactionary. As the Red Guards yell at him, we find out why: this physics professor had the gall to teach the theory of relativity, an idea that came from Western imperialists. After proudly refusing to confess to his “crimes,” the Red Guards, many of whom are his former students, bring his wife to the stage. In front of the frenzied crowd she criticizes him for his Western thoughts, betraying her husband to save herself. The crowd roars it support and the Red Guards, with faces seething with hate, beat him to death.

As Tania Branigan, the Guardian’s former China correspondent, shows in her gripping new book Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultura Revolution, the Three Body Problem’s opening scene was anything but unique during China’s Cultural Revolution. From 1966 to the Cultural Revolution’s end in 1976, “no household remained innocent. ‘Complicity’ is too small a word — comrade turned on comrade, friend upon friend, husband upon wife and child upon parent. You could build a career on such betrayals . . .” Branigan writes. Up to 2 million were killed and another 36 million persecuted for holding the wrong thoughts or just for their family background.

Red Memory features some of these harrowing stories and how people today are still trying to process it. Particularly appalling is Branigan’s retelling of Zhang Hongbing’s tale. In the waning days of the Cultural Revolution, Zhang heard his mother privately criticize Mao Zedong. A teenager at the time and indoctrinated in Mao thought, he and his father informed on her to the authorities, knowing that she could be executed for her comments. And she was. Zhang and his father did not attend her execution, but a family friend did, and he watched as the mother combed the crowded, likely looking for her son. Zhang now prostrates himself in front of the tombstone he had erected where she was shot in the head.

Then there are classmates of Song Binbin, one of China’s most famous Red Guards and who is often blamed for the first killing of the Cultural Revolution: the murder of vice principal Bian Zhongyun in August 1966 at one of Beijing’s most elite all-girls high schools. While not admitting to anything, Song had issued an apology and her classmates point out to Branigan the courage that took. But as Branigan notes, what these women were looking for was closure, not actual accountability.

But Red Memory does more than retell these horrific stories of violence and torture. Instead, its focus is on the competing viewpoints of the Cultural Revolution in China today, and this is what makes Branigan’s book particularly important. Outside of China, the Cultural Revolution is almost universally condemned. Inside China, where the discussion of the Cultural Revolution is increasingly suppressed, views are more mixed. Sure, there are those who see it as the worst period in modern Chinese history but Branigan also features those who cherish their experiences during the era. Branigan interviews a group of former “educated youths,” Red Guards, around 14 million of them, who were sent to the countryside for years after Mao tired of their fanaticism. The group Branigan interviews enjoy reminiscing about their time in the countryside. Then there is Zhou Jiayu, a Red Guard in Chongqing, a city that saw some of the most violent fighting between factional Red Guard groups. Zhou would eventually be jailed for beating rival Red Guards, but for this son of peasants, the Cultural Revolution was a time when the poor held power and education, health care were free and equally provided. A sharp contrast to what Zhou sees in China today – growing inequality and rampant government corruption. Finally, there are the performance actors who dress up as some of the Cultural Revolution’s leaders – Mao, Zhou Enlai, Lin Biao. Hired for parties, Branigan notes that “what was not permissible as history in China was allowed as entertainment.” There is a certain nostalgia for the era and for the young who never experienced it, an ignorance of just how violent it was.

But what is most interesting about this split view of the Cultural Revolution is the impact that it has on today’s ruling class. Some of Branigan’s most thought-provoiking chapters are on how two recent officials – Chongqing Party boss Bo Xilai and President Xi Jinping – use positive recollections of the Cultural Revolution to their advantage (although Bo, one of Xi’s main rivals, was eventually jailed for corruption early in Xi’s first term). With leaders in their 60s and 70s, the Cultural Revolution was a defining point in their young lives and no doubt shapes how they see the world. “It is impossible to understand China today without understanding the Cultural Revolution. Subtract it and the country makes no sense. . . .Unfortunately it is also impossible to truly understand the movement. . . .” Branigan states.

Branigan inserts more of herself in Red Memory than is usual for a work of non-fiction, offering her viewpoints on certain events and the phycological impact that the Cultural Revolution has had on China as a whole. At times, these insights are helpful, for example when she questions Zhang Hongbing’s sincerity for his mother’s death. But at other times it feels a little too intrusive and a little too much armchair psychology. But ultimately these are minor issues in an otherwise nuanced book. As Red Memory makes clear, we are unable to understand the Cultural Revolution because China has yet to collectively deal with the trauma of its past. But more importantly, with competing views, it could be that how the Cultural Revolution is ultimately remembered is not what the outside world would expect.

Rating:

Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultural Revolution, by Tania Branigan (W.W. Norton & Company, 2023), 254 pages.

Interested in purchasing Red Memory? Consider supporting your local, independent bookstore. Find the nearest one here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email