Where People Still Die of AIDS: China and the Importance of Grassroots Advocacy

This year Asia Catalyst celebrates its fifth anniversary. If you have never heard of Asia Catalyst, then you are missing out on this tiny but powerful U.S-based NGO doing work in China. Founded and headed by Sara L.M. Davis, aka “Meg”, a former China researcher at Human Rights Watch, Asia Catalyst is doing what others might think is unsexy work, but in reality is perhaps the most necessary work: assisting Chinese grassroots NGOs with developing the skills and best practices to become effective organizations.

Asia Catalyst is one of the few groups on the ground in China making civil society a reality. By training China’s nascent grassroots NGOs in the nitty-gritty of running a non-profit, Asia Catalyst guarantees that Chinese civil society will have a strong foundation upon which it can successfully grow. Asia Catalyst also teaches the tools necessary to effectively advocate both on the domestic and international levels.

China Law & Policy sat down with Meg Davis to discuss Asia Catalyst’s work with NGOs, its recently co-authored report with Beijing’s Korekata AIDS Law Center about the HIV/AIDS blood disaster, and what the future holds for civil society, rule of law and Asia Catalyst.

For those also impressed by its work and interested in supporting it, donations can be made here. For its Fifth Anniversary Campaign, Asia Catalyst’s Board of Directors has generously offered to match all individual gifts donated in 2012 (up to $8,000).

Click here to listen to the interview with Asia Catalyst founder & executive director, Meg Davis, or read the entire transcript below.

Length: 19 minutes (audio will open in a separate browser)

*****************************************************************************

[01:06] EL: Thank you for joining us today Meg. So five years ago, what inspired you to create Asia Catalyst?

[01:13] MD: It was really kind of an exciting moment in the development of Chinese civil society. You were starting to see a lot of small groups springing up around the country to address health issues and environmental issues. These were groups that were started by charismatic individuals who had a clear vision for the future, but maybe hadn’t worked at a non-profit before or had just worked at a similar kind of grassroots start-up. It was the fact that I had worked with some of these folks at Human Rights Watch in my capacity as a researcher there that led me to have relationships with them. When I left Human Rights Watch they didn’t really let me leave; they kind of followed along and said ‘can you look at this grant proposal,’ ‘can you help me to meet with this UN person,’ ‘I’m at risk of arrest, can I sleep on your sofa for a week.’ So there was a lot of that kind of stuff that eventually led to the development of Asia Catalyst.

[02:07] EL: Just in terms of the grassroots situation in China, you keep referring to these NGOs that you work with as “grassroots NGOs.” Can you perhaps just explain a little bit more about the NGO structure in China and how these “grassroots NGOs” that you help fit into that structure?

[02:25] MD: Grassroots is really an English appropriation of a Chinese term – caogen. A lot of the groups we work refer to themselves as  “caogen,” as grassroots groups. It’s their way of saying they are independent. In China, you can only really register at this stage as a non-profit, if you have, in most parts of the country, a sponsoring government institution. For groups that do policy advocacy, no sensible government official is going to stick their necks out and sponsor one of these groups to get registered. Some of them are unregistered and a lot of them are registered as businesses, as commercial enterprises.

“caogen,” as grassroots groups. It’s their way of saying they are independent. In China, you can only really register at this stage as a non-profit, if you have, in most parts of the country, a sponsoring government institution. For groups that do policy advocacy, no sensible government official is going to stick their necks out and sponsor one of these groups to get registered. Some of them are unregistered and a lot of them are registered as businesses, as commercial enterprises.

[03:03] EL: If these groups are unregistered with the government, how do they develop the skills? If you’re not there to help them, how would they develop the skills to become a professional and effective organization without you if they are kind of in the shadows?

[03:18] MD: Some groups that are more established are getting support from capacity building organizations that do exist in China. There aren’t many people who are offering what we provide to these very small start-ups which is really one-on-one tailored coaching. A lot of the groups we work with are founded by people with very limited education so we’re developing tools that don’t require a very sophisticated vocabulary that they can use to do strategic planning, budgeting, staff management, they can do basic qualitative research without a sophisticated background.

[03:51] EL: In terms of Asia Catalyst’s focus, you’re focusing right now on which types of grassroots NGOs? I imagine there are a lot of grassroots NGOs [in China], which are you focusing on?

[04:01] MD: There are more every year. We mostly work with groups involved in health and legal rights. That includes groups working on HIV/AIDS, some marginalized communities including lesbian and gay groups, sex workers, drug users, people living with HIV. But we’re starting also to work with groups that work on disability rights and with groups working on pollution and other kinds of health-related issues.

[04:26] EL: What caused you five years ago just to focus on health rights groups?

[04:31] MD: It was an area of growth and I think it’s also an area where forward-thinking, progressive government officials can easily engage. If you go to them and say ‘we want to support human rights groups that are working on democracy promotion or censorship issues,’ that’s hard for someone who is a devout believer in Communist Party ideals to support. But someone who is a socialist can get behind health rights because it is really is not that far removed.

[04:58] EL: So today, five years in, how many organizations in China does Asia Catalyst currently partner with and how does Asia Catalyst find its partners?

[05:07] MD: Currently this year we’re working with about 17 organizations around the country. They’re from all over the place; from northeast China to all the way down to Yunnan and southeast China as well.

[05:18] We find most of our partners through online, open applications and we do this because when I was starting Asia Catalyst, there was a growing number of NGOs but there was a very small number that had international partners or international funding and we really wanted to cast a wider net and get groups that maybe not everybody had heard about. I think we are starting to do that.

[05:39] EL: So just to follow up on that. That’s one of the things that I find exciting about Asia Catalyst is this open call for applications. I know you have a report on your website about how you put out an open call and that people can just come in. I know most US-based organizations do partner with Chinese organizations that have been recommended through other people, so a lot of the same organizations are getting support internationally. Sometimes some of those organizations – the US organizations – believe that it that these organizations are more reliable. But by opening your application process to the public, do you feel that you risk spending resources on grassroots NGOs that might not be as reliable and that might just disappear. What has your experience been?

[06:30] MD: It’s actually…our experience is the opposite. Our experience is that some people who become, frankly, kind of donor favorites don’t necessarily have very strong infrastructure, don’t have a core team, don’t have a strategic plan or a solid budget, don’t necessarily have strong financial controls. So by throwing the application process completely open, it’s a little bit more democratic, it’s a little bit more in line with the ideals that we espouse of transparency and accountability, and it means that groups, any groups that applies for one of our programs has to go through a process of being vetted which is quite intensive and a little bit painful for them. They have to submit a lot of materials, they have to go through multiple interviews, they have to provide references, and in that way we try to identify groups that have certain fundamentals and one of those is a core team. It’s easy to have one person who is very charismatic [as a] founder but that doesn’t necessarily mean that there is an organization behind them. We’ve learned that the hard way. So that’s one of the things that we try to identify through our intake process.

[07:33] EL: After you have done the intake and you find an organization that has been vetted, what kind of services does Asia Catalyst provide to help develop them?

[07:41] MD: The way our program is structured now, the first kind of level of engagement is through our non-profit leadership cohort which is a year-long program where 10 health rights group get intensive training in budgeting, strategic planning, and volunteer management. Out of that, we pick two people who will continue on for a second year who will then become training assistants with a small stipend. At the end of the second year, if they pass a certification exam, they can start their own cohort using our curriculum.

[08:15] Groups that go through the cohort then become eligible to get other kinds of assistance and sometimes that means leveraging our own donor connections to introduce them to donors, sometimes that means helping them come to international conferences. So it can mean a variety of different possible partnerships.

[08:29] EL: I also know that you guys have this survival skills guide. Is that accessible to Chinese NGOs in Chinese on the web?

[08:39] MD: It is. It’s available in English and in Chinese. We’ve circulated hard copies through our networks in China and we’ve also made it available for free download. That’s actually the most popular thing we developed is that tool kit which uses tools we developed with groups over the past years.

[08:53] EL: And that’s accessible to all grassroots organizations in China?

[08:55] MD: Absolutely. Any of them. And also our human rights curriculum which we’re still in the process of developing with Chinese and Thai partners which is called “Know It, Prove It, Change It” and is a three part curriculum series on how to analyze human rights issues, how to document them and how to conduct advocacy around them.

[09:15] EL: And then the organizations that you work with in China, I know you have this philosophy of “pay it forward” where they’re supposed to help others. Can you just talk more about that and how you make sure that happens.

[09:25] MD: That was something that came out of our initial partnership with the Korekata AIDS Law Center in Beijing. After we had worked with them for a couple of years and they were ready to become independent, we asked them for some input into our strategic plan and they said, ‘How about a pay it forward element where we would then help another organization with some element of their work?’ So some of the groups that we work with now that have had a little bit more experience, we ask them to assist with some of the other organizations whether it is advising on a project or giving them a little workshop or something else.

[09:56] EL: So then they are creating a real civil society where other organizations in China teach other organizations.

[10:00] MD: That’s the hope.

[10:02] EL: That’s cool. So I just want to also now turn to some of the substantive work that Asia Catalyst has published and co-authored, specifically, the March 2012 report that Asia Catalyst co-authored with Korekata AIDS Law Center entitled “China’s Blood Disaster: The Way Forward.” Can you just give our listeners a little bit of background on the report, what role Asia Catalyst played in drafting the report and how Korekata was able to obtain the information for that report?

[10:33] MD: Sure. I think as most people who follow China at all know, in the 1990s tens of thousands of people contracted HIV through a state-sponsored, for-profit blood collection scheme in which people were encouraged to sell their blood in ways that were unsafe and that spread tainted blood to whole villages of people. [Hospital blood supplies became contaminated, spreading HIV to more people.]

[10:54] Ten, fifteen years further down the line, a lot of those people are struggling with HIV and are still trying to get compensation and still trying to get some acknowledgement of what happened to them and their families. Some of them suffered just overwhelming losses. It’s really the largest blood disaster in the history of AIDS. China has had one, and certainly the US, Canada, France, Japan, every country has had a blood disaster but China dwarfs the others by several orders of magnitude.

[11:23] So activists and people living with HIV in China have been pushing, through petitioning and through lawsuits, to try and get compensation. The weak legal system in China has made it difficult for them. But in the past year or so we got some signals from UNAIDS that the government might be willing to engage on this issue and to address this vast need by creating a national compensation plan.

[11:23] So activists and people living with HIV in China have been pushing, through petitioning and through lawsuits, to try and get compensation. The weak legal system in China has made it difficult for them. But in the past year or so we got some signals from UNAIDS that the government might be willing to engage on this issue and to address this vast need by creating a national compensation plan.

[11:47] We were asked by UNAIDS to work with Korekata AIDS Law Center as they conducted research to document some of the cases. It’s not possible to document all of them when you’re a tiny, little NGO, but to gather some of the cases from different parts of the areas that were affected and to show what some of the challenges were with obtaining compensation.

[12:06] So Korekata conducted several dozen interviews, they got very rich testimony from people in very remote villages. I worked with them in training them on how to do the research and then how to analyze the data. We had a week of eating dumplings around a table and arguing about how a compensation fund should be managed which was one of the most fun things I’ve ever done. Imagine trying to make policy for a country of 1.2 billion. If you’re not someone already doing it it’s a challenging task. Based on that, Korekata drafted a report which we translated into English and was submitted to the UNAIDS and to what’s called the Red Ribbon Forum, a national platform for dialogue on HIV/AIDS policy.

[12:49] EL: When you say the Red Ribbon Forum is a national platform, is that a national platform within China?

[12:55] MD: It is. It’s unique actually and they have kept it a little bit quiet. Basically as far as I know it is the first platform in which the government and NGOs engage in a dialogue about human rights, and it’s about human rights and HIV/AIDS.

[13:09] EL: And just in terms when you say the government and NGOs, including these grassroots NGOs that are kind of in the shadows?

[13:17] MD: That’s right. Absolutely. It’s grassroots NGOs and it’s the Ministry of Health. And when I say dialogue it is often Ministry of Health officials giving a speech and then NGOs giving a speech. So it’s not really a very hands-on, face-to-face discussion a lot of the time. But it is a first to have them in the same room and talking to each other

[13:36] Out of that there was a working group [led by Professor Qiu Rrenzong] that then created proposals that went to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference which met in March, [and then to the National People’s Congress, and was submitted up from there.] So there is a proposal now for a national compensation fund that is in that process. So we’ll see.

[13:54] EL:So this report has basically gone to the high levels of the Chinese government and hopefully has some kind of impact?

[14:00] MD: Yes. I have written a lot of human rights reports in China and that’s the first one.

[14:04] EL: And in terms of the report, outside of the Chinese government, I know you received coverage with the South China Morning Post, but domestically, has the report received any media coverage in China or is this issue still a little bit too sensitive. I guess, how is the media handling the report and then just the issue in general?

[14:22] MD: We did what is called a soft launch, so we didn’t send it out to all our press contacts and Korekata also did not because it was the “Liang Hui,” the “Two Sessions Period” which is often politically sensitive. So we opted to do something that was a little bit more low key and just send it to a few key people we knew were interested in the issue and that would cover it. So there was a beautiful article by Paul Mooney in South China Morning Post, the British Medical Journal and then as it happened, the Shenzhen CDC, Center for Disease Control, also reported on it.

[14:52] EL: Wow, so this is having a lot of impact then. In terms of the report itself, when I read through it, what I thought was the most interesting as a attorney was just the difficulty that many of these people have in getting into the court system in order to compensation cases. So you can just explain to our audience how these cases are kept out of court?

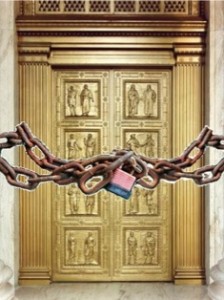

[15:18] MD: Sure. What’s happened in Henan province is that courts have flat-out refused to accept cases. So a lawyer will approach the court, say that he wants or she wants to submit a case for consideration and the court clerk will just take it and then bring it back to him and say ‘sorry we cannot accept this case because it relates to HIV AIDS.’ In Henan, courts are saying that they have been issued an order from on-high not to handle any cases relating to HIV AIDS of any kind.

[15:49] EL: Have you ever seen this actual order?

[15:52] MD: No one has seen it. No one has ever seen this order.

[15:55] EL: And Henan is kind of the epicenter of the crisis?

[15:57] MD: Henan is the one that’s the hardest hit province in the whole region. [In other provinces, courts sometimes accept cases, but plaintiffs then face many procedural barriers to getting a judgment. In a few cases, people have gotten judgments but then never succeeded in getting them implemented.]

[16:01] EL: So what I thought actually was really interesting is that in your report you actually had a list of 26 HIV/AIDS compensation settlements where you document whether it was an out of court settlement or an in-court settlement or a court judgment. There were actually 6 cases where it was either a court-mediated settlement or a court judgment and they actually had the highest awards when I compared it to others. And even in one of them, what I thought was interesting, the one out of Heilongjiang ordered over $30,000 for emotionally damages.

[16:38] MD: Heilongjiang is a good [place] to be a victim of a bad thing.

[16:42] EL: Why are some courts taking these cases, or do you not know?

[16:47] MD: So Heilongjiang was very early on. It’s a northeastern province in China, very sparsely populated, there was not a big blood disaster there. So some provinces like Henan, it is tens of thousands of people. Heilongjiang it may be a few thousands or it may be less, we don’t really know. And so, I think what’s happening is that early on some provinces said ‘Fine, no problem, let’s address this.’ But other provinces said ‘We are going to open the flood gates and we cannot cope with this.’ And that’s part of the reason why we are calling for a national compensation fund.

[17:21] EL: Because you’re seeing such a disparity between provinces?

[17:24] MD: Yes, it’s deeply unfair.

[17:25] EL: Do you know….I mean, it was kind of unique, I mean as an attorney, seeing a judge give out a huge amount of money for emotional harm is even unique in the United States, let alone in China. Do you have any idea why?

[17:39] MD: I don’t and no one has been able to reach the lawyer in that case, so we don’t know all the details. That was a case that happened fairly early on also. So it gave a lot of people false hope I think in other places.

[17:52] EL: In terms of new cases, I know that you had reported…Asia Catalyst had reported on its blog that there’s been a new case that a court has actually accepted about HIV/AIDS and privacy. Do you think this is a result of publicizing the issue more? What do you think is happening there?

[18:07] MD: I don’t…I mean, I don’t know. There have been a few attempts to litigate on discrimination and this was actually sort of like a discrimination case. I think there is starting to be a little bit more awareness and more courts are accepting cases related to discrimination. And privacy issues are probably an easier sell. But the blood disaster remains very, very hard to litigate on.

[18:33] EL: So it sounds like that in a short amount of time Asia Catalyst has been able to assist a good number of grassroots NGOs achieve justice for some of society’s most vulnerable. What do you see for the next 5 years?

[18:44] MD: Well, we are continuing to build on our work in China. Some of the groups that come out of the cohort, we will be working with them to help them conduct their own research and do advocacy and hopefully building a system that will then self-perpetuate where people who come out of our program start to train others and it scales up and becomes really something that is locally managed . We are also beginning to look at Myanmar and other countries in Southeast Asia to see whether we can take the tools and experience we have from China and make them work in other locations as well. So we will see how that develops.

[19:16] EL: Okay, well that’s very exciting, it’s exciting times for Asia Catalyst and thank you for joining us today Meg.

[19:21] MD: Thank you so much.

******************************************************************************

To learn more about Asia Catalyst events or to support its work, please visit Asia Catalyst’s website at www.asiacatalyst.org. For its Fifth Anniversary Campaign, Asia Catalyst’s Board of Directors has generously offered to match all individual gifts donated in 2012 (up to $8,000).

To learn more about Asia Catalyst events or to support its work, please visit Asia Catalyst’s website at www.asiacatalyst.org. For its Fifth Anniversary Campaign, Asia Catalyst’s Board of Directors has generously offered to match all individual gifts donated in 2012 (up to $8,000).

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email