Walls of Weakness

Almost daily, Donald Trump talks about building a wall on the U.S.-Mexican border. According to him, it’s needed to keep immigrants out. It was his commitment for a border wall that lead to a 35-day government shutdown back in January and, when Trump failed to secure any funding for his wall, caused him to declare a national emergency. But Trump isn’t the first world leader to look to a wall as a way to keep people out. That dubious honor belongs to the Chinese. It was the Chinese who built a 5,500-mile-long wall along its northern border to keep out the different tribes just outside its borders and to maintain the purity of their Han culture.

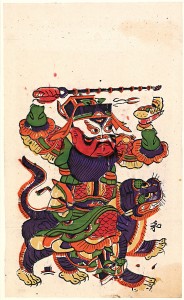

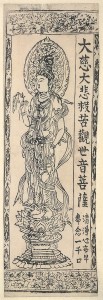

In fact, he Chinese have been building walls for over 2,000.[1] Starting with the Qin dynasty (China’s “first” dynasty), a wall was seen as a way to keep foreigners to the north out. But for most of China’s history, this wall was largely mounds of rammed earth. It wasn’t until the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644 AD) that a more permanent structure of mortar and bricks was finally contemplated.

But the Ming did not build a wall out of strength; it built it from a place of weakness. After more than a century of expansion in trade and influence, with one of the most powerful navies in the world that promoted trade as far off as the coast of east Africa, by the mid to late 1400s the Ming Dynasty began to retreat inward. It no longer sought trade abroad and its global power and influence receded. And its aversion to trade was not just restricted to the maritime sphere; it also included the tribes to the north. It was the Ming’s trade embargo on arms, copper, iron and horses with its northern neighbors that caused the northern tribes to unite and begin constant attacks on the Ming.

With these attacks, the Ming began to spend more and more resources on building the Wall. For the next 150 years, the Ming’s sole focus – and at great expense to its empire – was the defense of its northern frontier, including constant repair and reinforcement of the Great Wall. What tourists see today – the reconstructed Wall at Badaling and Mutianyu or the wild Wall at Simatai and Gubeikou – are relics of this emblem of a dynasty in decline. In 1644 the Manchus, a non-Han Chinese tribe to the north, breached the wall, defeated the Ming and established the Qing Dynasty, a non-Chinese dynasty that would rule until the dynastic model was overthrown in 1911.

But

the Great Wall is more than a symbol of ineffectiveness; it also demonstrates

the danger in a country’s own isolationist policy. For the first 150 years of

the Ming Dynasty, China, through effective trade relations with the northern

tribes, was able to keep peace with its neighbors. It wasn’t until it began to

turn inward and cut off trade that trouble emerged. But instead of reversing

its policy, the Ming dug in, directing more and more of the empire’s resources

and attention to building the Great Wall.

Trump

appears to be on the same collision course with history, taking the American public

with him. In addition to shutting down the government for over a month, a move

that appears to have

cost the American public $11 billion in lost economic

opportunities, by declaring a national emergency, Trump now seeks to siphon off

from

other federal agencies $8 billion to build his wall.

In addition, instead of addressing some of the causes of the current

immigration trends at the U.S.’ southern border – such as the failing

central American states of Honduras, Guatemala and

El Salvador – Trump is digging in his heels, punitively

threatening to cut off all forms of aid to those countries.

Like with the Ming Dynasty, Trump’s demand for a wall is not just a call for

something ineffective –most undocumented individuals in the U.S. are a result

of visa

overstays not physically walking over the border – it is

also continues the United States’ path on an isolationist, anti-trade and

anti-engagement strategy. For the Ming it was the beginning of their decline.

Time will only tell if the same holds true for the United States.

[1] For this post, CL&P relies on two sources for the history of the Great Wall of China: Jacques Gernet, A History of Chinese Civilization (Cambridge University Press, 2nd Ed. 1996) and Peter Hessler, Walking the Wall (The New Yorker, May 21, 2007).

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email