Heaven Help the Working Girl: The Impact of the Law on Women in China

Sure women might not demand that their names be on the deed even after giving money to purchase the house, but does that matter in the case of divorce in China? As Dr. Leta Hong Fincher points out in Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China, you bet that matters. Changes in the law in 2011 – requiring physical proof of monetary contribution – has diminished women’s ability to claim their rightful part of the marital property in the case of divorce. By why this change? And why now? Fincher expounds upon these questions in Part 2 of her interview with China Law & Policy and informs us why the rest of the world needs to wake up and care about what is happening to women in China.

Read the transcript below of Part 2 of this two-part series or click the media player to listen to the podcast.

Length: 10:15 minutes

For Part 1 of this interview, please click here.

******************************************************************************

EL: To switch gears a bit, you mention in your book some of the laws that impact this. You discuss the Supreme

[People’s] Court 2011 Interpretation of China’s Marriage Law. You basically argue that this Interpretation – which in cases of divorce only allocates property to those whose name is on the deed absent some exceptions – denies women even more rights in the property market. Can you give a little bit more background on this Interpretation? Also, do you have any background on what caused the Supreme People’s Court to issue this Interpretation?

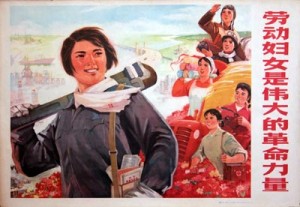

LHF: Effectively the Marriage Law was originally a real cornerstone of the Communist Revolution and it gave women rights to property, the right to divorce, all sorts of new rights. Over the years actually women’s rights to common marital property were strengthened. But in 2011, with this new judicial interpretation, effectively if the woman is unable to prove through legal, financial receipts that she put in a certain amount of money toward buying the home, she’s not entitled to that home in the event of a divorce. None of the women that I interviewed kept any receipts of their financial contribution to the homes. Moreover, money is fungible. So there many ways in which women’s money – if they are working women working for pay – there are many ways in which their pay is supporting the household. The man’s money may be going directly to paying off the mortgage so there is a receipt for the man’s contribution to the home.

This law is really detrimental to women’s property rights. Now, what I have heard anecdotally – I wasn’t specifically researching why the court issued this new judicial interpretation – but what I’ve heard anecdotally from some lawyers is that the Court was deluged with letters from parents of men who wanted to protect their sons when they got married. They didn’t want the wives of their sons to have any share in the home because the parents tend to put up so much money to buying these homes for their own sons. Because of China’s rapidly rising divorce rate, I’ve also heard that the Court simply wanted to simplify divorce rulings; just get these cases through the court fast.

But it has been an incredibly controversial interpretation and a lot of women across China are very upset about it but there’s no organized movement to protest it because organizing and protesting is so difficult [in China].

EL: I guess in looking at the Supreme People’s Court interpretation and how that has a negative impact on women, one of the things though that has happened recently is that China has had its first gender discrimination lawsuit in employment. That seems like a positive development in terms of women’s rights. So how do you gel the fact that in a country where the court can reject cases, so they allowed obviously this case to be heard and even though it settled, they did allow it and its been published in the newspaper. How do you gel that kind of a development with the leftover women and the 2011 Marriage Law Interpretation?

EL: I guess in looking at the Supreme People’s Court interpretation and how that has a negative impact on women, one of the things though that has happened recently is that China has had its first gender discrimination lawsuit in employment. That seems like a positive development in terms of women’s rights. So how do you gel the fact that in a country where the court can reject cases, so they allowed obviously this case to be heard and even though it settled, they did allow it and its been published in the newspaper. How do you gel that kind of a development with the leftover women and the 2011 Marriage Law Interpretation?

LHF: Well, Chinese society is certainly not static and there are some legal success. That gender discrimination lawsuit was very important and it set an important precedent. But the fact is that there are so many other systemic ways in which women’s rights and gains are being reversed in the past two decades. One successful lawsuit here or there doesn’t fundamentally change the situation for the vast majority of women. Most notably there is still no specific law on domestic violence. Feminist lawyers and activist had been lobbying for over a decade to pass a law. And they’ve drafted the language, it’s all ready, but it simply hasn’t been passed.

EL: To go back to that because your book ends where you do discuss some individuals that are trying to change things a little bit, incrementally, but I have to admit it didn’t seem like there was going to be a lot of change from them even though they’re brave in what they are doing. It sounds like, based on what you say you don’t see a lot of change happening soon. Is that correct? Or if you do see any change, where do you see it coming from?

LHF: I certainly don’t see change coming from an organized nationwide women’s rights movement simply because

the political atmosphere is too severely oppressive for that to happen. But what does give me hope is that individual women can make choices in their own lives to avoid getting trapped in a very discriminatory system.

For example, there are women in their late 20s who have told me that they refuse to ever get married because marriage is a bad institution for women in China. They see this as an empowering choice. That doesn’t mean that they’re never going to have a lover or a boyfriend or maybe they’re lesbian. But there are individual ways in which women can act to empower themselves. But once they enter the institution of marriage it is very, very difficult. Marriage as an institution doesn’t protect women’s rights.

Contrary to the myths that are spread by the propaganda of the state media that single women in China are extremely miserable and lonely, I see the reverse. Single women are the ones who tend to do better. They don’t have husbands holding them back, telling them what to do; they have a lot more freedom. Women who are married, if there is any problem at all in the marriage, they’re extraordinarily vulnerable.

EL: And just in closing, you’re book is a fascinating book and I do recommend for everybody to read, especially if they really want to understand China today and women in China today. But why do you think the rest of the world should be paying attention to this issue if at all?

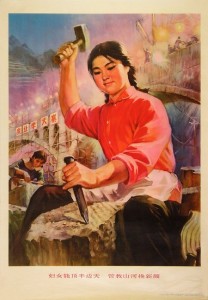

LHF: Well the thing is that, let’s put aside the issue of fair treatment for women. Obviously women are being treated unfairly in China and are being discriminated against. But, as an economic issue, it’s very important. China’s obviously becoming increasingly a driver of global economic growth. The fact that women are basically being told by the government that they should stop working so hard and return to the home is going to end up having very damaging long-term economic consequences for China.

There’s already a declining labor force participation among women, particularly in the cities according to the latest census results; there’s a dramatically widening gender income gap. These are the most talented women in the country and if you’re telling the most talented female workers in China – it’s okay just leave the workforce – that’s going to hurt China’s economy. Of course if China’s economic development is hurt, if it is destabilizing, that’s going to affect the rest of the world. So it is something the rest of the world should be interested in.

EL: I want to thank you again for spending time with China Law & Policy. Just so our readers know, Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China

, that can be purchased at amazon.com

. Thank you again.

LHF: Thanks so much for having me.

************************************************************************************************

For Part 1 of this interview, please click here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email