The Human Toll of a Cold War: “Agents of Subversion” and “Lost in the Cold War”

Few Americans know the story of John “Jack” Downey, the United States’ longest-held prisoner of war who served over 20 years in a Chinese prison. But given the current broken relationship between the U.S. and China, it’s important to understand Downey’s ordeal and the human toll of the last Cold War. Fortunately, two new, thought-provoking books, Lost in the Cold War: The Story of Jack Downey, America’s Longest-Held POW, written by John T. Downey with explanations by China political scientist Thomas Christensen and a moving epilogue by Downey’s son, John Lee Downey, and Agents of Subversion: The Fate of John T. Downey and the CIA’s Covert War in China, by China historian John Delury, recounts Downey’s story and the repercussions of trying to “win” a cold war.

Downey’s story starts with America in 1950. Communism was spreading across the world and many in D.C. were looking for someone to blame for the “loss” of China to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) the year prior. Senator Joseph McCarthy settled upon the China hands at the State Department, hauling them before the Senate to accuse them of being Communist sympathizers. By October 1950, the CCP had entered the Korean War, turning the tide against the Americans forces. For the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency (“CIA”), overthrowing the CCP through covert action became a priority. Initially, the CIA used Chinese operatives, agents it called “the Third Force” because of their lack of allegiance to the CCP or the prior party that had governed China, the Kuo Min Tang (“KMT”). With only minimal training, the CIA would clandestinely air drop these Third Force agents into a village in China, hoping they could go on to form a successful resistance movement against the CCP. But after the corruption of the KMT and years of war, most Chinese were not interested in overthrowing the CCP. Of the CIA’s 212 Third Force operatives it dropped in China, 111 were captured and 101 killed.

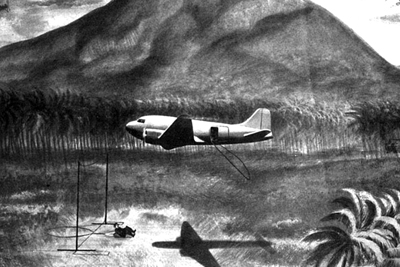

But these abysmal numbers did not stop the CIA. Instead, it hatched an even more absurd plan: send American agents into China to try to help these Third Force operatives. In November 1952, the CIA sent two of its American agents into Chinese airspace over Manchuria to physically pick up one of these Third Force operatives: Jack Downey, only a year out of Yale University and with no knowledge on China, and agent Richard “Dick” Fecteau, also a recent grad with zero China knowledge. Their plane was to fly low over a meeting point, with Downey and Fecteau holding out a long hook that the operative was to attach to his vest, and as the plane ascended, Downey and Fecteau would pull the hook up into the plane, bringing the Third Force operative with it. But the operative had already been discovered by the CCP weeks earlier, had flipped, and CCP forces were awaiting Downey and Fecteau’s plane. As soon as the plane was low enough, CCP forces shot it down, killing the pilots and capturing Downey and Fecteau.

For two years, the Chinese government kept secret the capture of these two Americans. The CIA presumed the two dead and sent letters to their families to that effect. But in 1954, when Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai made public that the two were very much alive and had been convicted of espionage, with Downey receiving a life sentence and Fecteau twenty years, the U.S. government went into crisis mode. But instead of admitting the truth, that they were in fact spies, the U.S. government concocted the story that the two had been civilian employees of the army and their flight from South Korea to Japan had been blown off course into Chinese airspace due to a storm.

For the next twenty years, the U.S. government maintained this fiction to the world and to its own people even though between 1954 and 1966, there were at least two opportunities to free the men. All that the U.S government would have to have done was to admit that the two were CIA operatives. Then-Secretary of State John Foster Dulles refused. To him, such an admission would be a victory for the Communists and every Administration went along with his decision. It would not be until the early 1970s, and the formation of a new China policy by President Richard Nixon, that there would be any movement. With warming relations between the two countries, Fecteau was freed on December 1971, but Downey, always viewed by the Chinese as the mission’s leader, only received a reduction in his life sentence. Finally, at a press conference about Vietnam POWs in January 1973, Nixon admitted that Downey was a CIA agent. Two months later, on March 12, Downey would cross the Chinese border into Hong Kong, finally a free man.

Lost in the Cold War is Downey’s memoir of the mission, recounting his zealousness in signing up for the CIA during his senior year at Yale (“Suddenly, my life had purpose”), his training, his capture, and then how he mentally and physically survived close to twenty-one years in a Chinese prison. Written in secret and only discovered by his family after his death in 2014, Downey’s writing style is engaging, making his ordeal into a page-turner. Interestingly, he harbors little resentment against the Chinese government, accepting that a life sentence was appropriate for what he did – unlawfully fly into Chinese airspace with the intent to overthrow the CCP. There is also no ill-will toward the U.S. government even though years of his life were wasted because of Dulles’ belief that negotiating with Communists was below him. Although Downey doesn’t express any anger, the reader cannot help but feel it for him. When Downey returns to Connecticut in 1973, he visits Yale; it was his memories of Yale, where he was a popular star athlete, that sustained him through prison. But all he finds on campus are ghosts. When he reunites with some college friends he sees that Yale is long behind them. “They had homes, jobs, wives, and children to enjoy and worry about. To them, the years at Yale were a distant memory. To me college was yesterday. . .In many ways, I was still twenty-two.” When he visits his sick mother, she firmly grasps his hand, unable to let go of the son she had to fight her own government to bring home.

How could the U.S. government allow this suffering to continue for 20 years and what was it all for? That is where Christensen’s chapters become important. For the majority of Americans today – two-thirds of whom were born either in the waning days of the Cold War or after it was over – the Cold War is nothing more than a plotline in a movie. Christensen reminds us that at the time, both the U.S. government and the American people really believed that every last resource had to be used to fight Communism. What we perceive as immoral choices today – letting Downey and Fecteau rot in a Chinese prison – were perceived as necessary to protect America. But even with this perspective, the failure to put a human life first still seems unnecessarily harsh. Downey’s son, whose moving epilogue is beautifully written and presents Downey as a kind, if somewhat tortured father, is much less forgiving. When he recounts the “celebration” the CIA held for his father and Fecteau in 2010, his tone is biting and rightfully so, reminding the reader of the human toll of all this.

Delury’s Agents of Subversion is an important supplement to Downey’s memoirs, artfully putting Downey’s story into the larger narrative of the United States’ changing society in the early 1950s. It starts with the intellectual battles that were brewing in post-World War II America, between those who thought the U.S should focus on its own domestic issues and those who believed that any means that could eliminate Communism from the world should be used. Ultimately those who wanted to take on Communism through subversive and covert operations – especially John Foster Dulles and his brother, Allen Dulles who was the CIA’s director at the time – won the day.

Further, by using original Chinese language sources, Delury shows that instead of fermenting revolution in China, the CIA’s efforts had the opposite effect: they justified Mao’s fear that the United States was seeking to undermine his rule, and validated his suppression and surveillance of the Chinese population. Delury also recounts the U.S. government’s response to the failed mission, its subsequent cover up, the constant pressure of Downey’s mother to free her son, and the road to Fecteau and Downey’s release after Nixon takes office. With deep research and a well-written narrative, Agents of Subversion is an important contribution to the intellectual history of the United States in the 1950s as well as its policy toward China.

Today, the U.S.’ China policy seems to be circling back to a cold war mentality of the 1950s and 60s, with increasing anti-China rhetoric coming from both sides of the aisle. There are aspects of the current Chinese regime that undermine a lawful and human rights-respecting world order that the U.S. must combat, but a complete vilification of the country does not serve that goal. And, as in the case with Jack Downey, it may even cause us to lose sight of our own values. Lost In the Cold War and Agents of Subversion are timely reminders that when ideological stakes are running high, our government is not above lying to its own people or forsaking its own citizens.

Lost in the Cold War: The Story of Jack Downey, America’s Longest-Held POW, by John T. Downey, Thomas Christensen and, John Lee Downey (Columbia University Press, 2022), 344 pages.

Rating:

Agents of Subversion: The Fate of John T. Downey and the CIA’s Covert War in China, by John Delury (Cornell University Press, 2022), 408 pages.

Rating:

Interested in purchasing these books? Consider supporting your local, independent bookstore. Find the nearest one here.

*******Correction: An earlier version of this article mistakenly referred to Eugene McCarthy instead of Joseph McCarthy. This has now been corrected. Apologies.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email