Stealing Suspects? The Interesting Case of of Chen Yongzhou

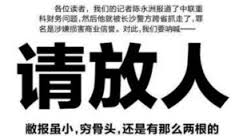

Last month’s drama surrounding the detention of journalist Chen Yongzhou’s (pronounced Chen Young-joe) by Changsha police, and his employer’s front page plea for Chen to be freed (“Please Release Him“), sent shock waves through the China-watching world. Was a local, albeit scrappy newspaper really taking on another city’s public security forces? Was it really publicly shaming them and essentially implying that the Changsha police were on the take?

But for many Americans watching these events unfold, the most puzzling aspects of the situation was not so much the David-and-Goliath narrative of the New Express newspaper confronting the Changsha public security bureau. Rather, most Americans were probably confused about two things: (1) police in one province can just go to another province and willy-nilly take someone away? and (2) defamation is a crime in China? This post will focus on the former.

Cross-Border Journalism Leads to Cross-Border Detention in China?

Chen and his colleagues at New Express are part of a new breed of journalist in China – muckrackers looking to hold powerful interests responsible and seeking to expose the truth that is often kept hidden by the government. For the past 18 months, Chen’s focus had been on Zoomlion, a construction equipment maker located in Changsha, Hunan province. Zoomlion is no ordinary construction equipment company; it is the country’s second largest construction company and in a country where construction is non-stop, that means wealth and power has accrued to the company.

Although Chen and New Express are located in Guangzhou – a city over 400 miles from Changsha and located in an entirely different province –

it is not peculiar that it chose to write and publish articles about Zoomlion. In China, where the local governments and local businesses are often in a symbiotic relationship and where the local Party is the law, it is commonplace that the local newspaper does not write about the corruption in its midst. Instead, it is an outsider newspaper – one as far away as Guangzhou – that will pick up the story.

Chen’s articles on Zoomlion fit this pattern. According to Bloomberg, Zoomlion’s controlling shareholders are Hunan State-Owned Assets (holding 19.97% of all A shares traded on the Shenzen exchange) and the Hunan government (owner of 16.2% of all outstanding shares of the company).

By May 2013, Chen was writing hard-hitting articles uncovering facts about the company that suggested it falsified its sales figures and was committing fraud on the market; a serious allegation for a company that trades on both the Shenzhen and Hong Kong exchanges. After his May 27, 2013 article, Zoomlion’s shares took a 5.4% hit on the Hong Kong stock market. While it denied Chen’s allegations, Zoomlion could not have been happy. But what is a Changsha company to do when the reporter and his newspaper are located in Guangzhou?

As far as the world knew, Zoomlion did nothing. But then on October 23, 2013, New Express stunned the world with its front page editorial acknowledging that the Changsha police had come to Guangzhou, detained Chen, and brought him back to Changsha where he remained in detention. The allegations: that Chen’s articles were false and defamed Zoomlion.

But do the police in one city have the power to swoop into a city in a different province and take away a suspect back to their home city? To Americans, this seems illegal. In the United States, because each state is sovereign within its territory, New York City police cannot just go to Boston and arrest the suspect they think did the crime. Rather, the New York City police must go through the legal proceeding of extradition: the New York City police must present the indictment to the Governor of Massachusetts who then has little choice but to consent to the arrest and orders Massachusetts or Boston police to arrest the suspect and eventually hand him over to New York City police to bring back to New York City.

In China, things are not that different. Like in the U.S., there is a recognition that at times, a criminal suspect might be living outside the confines of a local police bureau. The new Criminal Procedure Law (“CPL”)and its interpreting and implementing regulations – in particular the Ministry of Public Security’s “Procedural Regulations on the Handling of Criminal Cases by Public Security Organs (revised 2012)” (“MPS Regulations” or “Regulations”) – do contemplates this fact. Article 24 of the CPL makes it clear that by default jurisdiction of a criminal case is based on where the crime was committed. The MPS Regulations re-affirms this. Article 15 of the MPS regulations gives jurisdiction of a case to the public security bureau at the “site of the crime”, a term it defines as including not just the site of the actual criminal acts, but also any location where the consequences of the crime occurred. For a newspaper or online article, the consequences of the crime might be felt in a great number of locations, and the first public security bureau to file the case will exercise jurisdiction. The public security bureau at the place of the suspect’s residence can have jurisdiction when more appropriate, even if it isn’t a site of the crime.

In China, things are not that different. Like in the U.S., there is a recognition that at times, a criminal suspect might be living outside the confines of a local police bureau. The new Criminal Procedure Law (“CPL”)and its interpreting and implementing regulations – in particular the Ministry of Public Security’s “Procedural Regulations on the Handling of Criminal Cases by Public Security Organs (revised 2012)” (“MPS Regulations” or “Regulations”) – do contemplates this fact. Article 24 of the CPL makes it clear that by default jurisdiction of a criminal case is based on where the crime was committed. The MPS Regulations re-affirms this. Article 15 of the MPS regulations gives jurisdiction of a case to the public security bureau at the “site of the crime”, a term it defines as including not just the site of the actual criminal acts, but also any location where the consequences of the crime occurred. For a newspaper or online article, the consequences of the crime might be felt in a great number of locations, and the first public security bureau to file the case will exercise jurisdiction. The public security bureau at the place of the suspect’s residence can have jurisdiction when more appropriate, even if it isn’t a site of the crime.

As Jeremy Daum, research fellow at the Yale Law School’s China Law Center and founder of China Law Translate, pointed out recently, the Criminal Procedure Law and MPS Regulations clearly address activities by police outside of their geographic area – what Americans would likely compare to extradition.

An entire Chapter of the Regulations – entitled Cooperation in Case-Handling (Chapter 11, encompassing Articles 335-344) – specifically deals with these situations. As Daum noted, in terms of detaining a suspect, “Articles 339 and 340 [of the MPS Regulations] describe situations where police either take custody of someone in another jurisdiction or request that local police act on their behalf. Generally, the outside force has an obligation to contact the locals and to have the necessary authorizing paper work with them, and the locals have an obligation to facilitate.”

At this point, this pattern is not that different from what occurs in the United States when one state seeks to extradite a criminal suspect.

Although there a few, technical grounds upon which a U.S. governor of one state can deny another state’s extradition request, in general, extradition is mandated by the U.S. Constitution if the other state presents the indictment. The requesting state can go to federal court and compel the governor to extradite the suspect if she refuses on illegitimate grounds.

But where China differs from the U.S. in its proceedings is that the requesting police physically go to the local police’s territory to take the suspect back to their city. In accordance with Article 340, after the local police apprehend the suspect, the outside police must immediately pick up the suspect and bring him back to its territory. In fact, Article 122 requires that the outside police do so within 24 hours.

Was Chen Yongzhou Properly Detained?

It does appear that Chen was in fact properly detained in accordance with the MPS Regulations. Whether the Changsha public security bureau’s underlying claims against Chen are just is less apparent, but in terms of the procedure for cross-provincial transfers of a suspect, the Changsha public security officials likely complied with the Regulations.

Here, the Changsha police likely have a valid argument that the crime occurred in its jurisdiction or its consequences were the most strongly felt in its jurisdiction, giving it the right to assert its jurisdiction. Zoomlion, the entity that was allegedly injured by Chen’s articles, is located in Changsha.

According to a Freedom House bulletin, on October 18, 2013, after being summoned, Chen went to the Guangzhou police station. Once there, according to an article from the China Times News Group, Changsha police confronted Chen with a document listing his crimes and then placed him into its custody for transfer to Changsha.

It appears that the Changsha police complied with the MPS regulations concerning “Cooperation in Case Handling:” (1) Chen was summoned to the local police station by the Guangzhou police, (2) while in the Guaungzhou police station, the Changsha police presented him with a document listing his crime (perhaps the required authorizing paperwork), and (3) Chen was immediately transferred to the Changsha police and brought to a Changsha detention center within 24 hours.

Although the underlying criminal charges reek of corruption and a Changsha police department possibly at the beck and call of Zoomlion, it is still important to recognize that the Changsha police likely followed the law in obtaining custody of Chen. To ignore this fact does a disservice in criticizing other aspects of this bizarre case.

One such bizarre aspect is Zoomlion turning to the criminal law for a charge of defamation. Is this legal? Find out in part 2 of this article posted here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email