To Never Forget? China’s Cultural Revolution

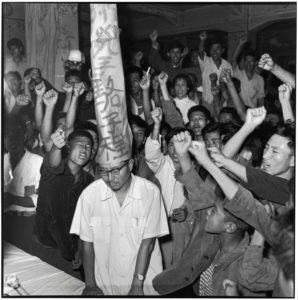

Public struggle session during the Cultural Revolution

Tomorrow will mark an important anniversary in China, an anniversary that will neither be celebrated nor condemned by the Chinese Communist Party; an anniversary that can only be acknowledged privately, by the millions who lost much; an anniversary that is not admitted to by the perpetrators who destroyed so many. For May 16, 2016 is the 50th anniversary of the start of China’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a decade-long, and ultimately senseless, political movement that shutdown Chinese society and resulted in the deaths of at least 1.5 million people, with tens of millions more publicly persecuted.

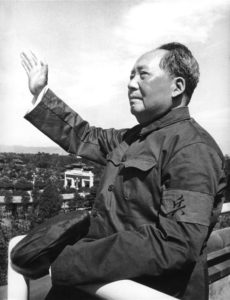

The Cultural Revolution began as a way for Mao Zedong to re-assert his leadership and consolidate his power. Only eight years prior, in 1958, Mao launched what history would also determine a worthless campaign – the Great Leap Forward. Less than 10 years after establishing the People’s Republic of China, Mao was gung-ho to move China to the next stage of communism – complete collectivization of farming and industry. China was nowhere near ready, resulting in one of the worst man-made famines of the 20th century, with over 30 million dying of starvation and other related disease. With that debacle, Mao, and with him, Mao Zedong Thought, were marginalized. For a brief period in the early 1960s, more pragmatic communist leaders like Liu Shaoqi (pronounced Leo Sh-ao Chee) and Deng Xiaoping, took control. Under their leadership, China pulled back from complete collectivization and permitted some economic liberalization, allowing society to get back on its feet.

Mao Zedong uses the Cultural Revolution to regain power and legitimize his ideology

But China’s development was short-lived. On May 16, 1966, Mao, at a Party meeting, came out of his semi-retirement and announced the start of the Cultural Revolution. In a notice to the Party – as well as to the Chinese people – Mao warned:

Those representatives of the bourgeoisie who have sneaked into the Party, the government, the army, and various spheres of culture are a bunch of counter-revolutionary revisionists. Once conditions are ripe, they will seize political power and turn the dictatorship of the proletariat into a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. Some of them we have already seen through; others we have not. Some are still trusted by us and are being trained as our successors, persons like Khruschev for example, who are still nestling beside us.

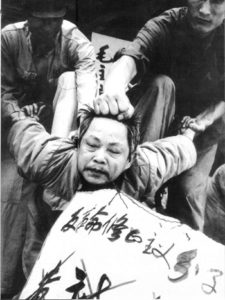

What ensued were ten years of political purges, including the mysterious deaths of two of Mao’s rivals – Liu Shaoqi and Lin Biao (pronounce Leen Bee-ow), as well as criticisms, abuse and murder of millions of innocent Chinese people as Mao sought to rid China of its “bourgeoisie” elements. Mao permitted Chinese society to resort to violence, carte blanche, to achieve his objectives. Anyone who had a family history of privilege, no matter how far back or how minor, was a target. As were intellectuals or anyone who did not appropriately parrot the words of Mao. These “counter-revolutionaries” would be subject to public humiliation, physical abuse and, at times, death by the hands of their families, neighbors and fellow countrymen. Many would also take their own lives. Schools were disbanded, work was minimal and “struggle sessions” constant. While the most violence erupted in the late 60s to early 70s, the Cultural Revolution was not over until Mao died on September 9, 1976.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

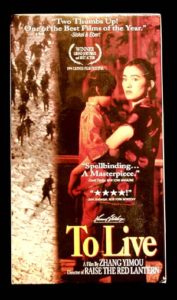

Although the Cultural Revolution is not fully taught in schools in China and government-supported amnesia is the status quo, stories of that bleak time still emerge. The author Yu Hua has probably done the most to keep these memories alive. “To Live,” one of his many books about ordinary people trying to get through the insanity of the Cultural Revolution, is a best seller in China and was made into a celebrated motion picture

by the famed director Zhang Yimou.

But more recently, ordinary citizens are demanding that the Cultural Revolution not be forgotten. Last month, on the eve of the Tomb Sweeping holiday in China, where families return to grave sites to pay their respect to their dead relatives, retired Chinese Supreme People’s Court judge, Cai Xiaoxue, explained in a blog post that he cannot. During the onset of the Cultural Revolution, his mother, a teacher, was constantly interrogated by her colleagues, not permitted to return home and in June 1966, died in their custody. Judge Cai’s family did not find out about her death until a month later, by which time her ashes were nowhere to be found. In 1969, after undergoing constant and public humiliations, writing various self-criticisms, and being fired from his post at the publishing house because he was a “capitalist roader,” Judge Cai’s father took his own life. Fifteen-year old Cai is the one who discovered the body and who, the next day, was required to attend a struggle session against his dead father. He was forced to sit in the front row.

Today, Judge Cai has no ashes to honor on Tomb Sweeping Day. His father’s ashes also were never returned. But he has purchased a plot where all he was able to bury were his father’s writings and his mother’s clothes. On the tombstone are carved only two words: Never Forget (勿忘). According to Judge Cai, only by remembering the horror can China ensure that that nothing like the Cultural Revolution happens again.

President Xi Jinping, trying to be more Mao than Mao?

What makes Judge Cai’s story – and this 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution – particularly significant is that the current leadership has recently resorted to some of the methods used by Mao and the Red Guards. Like Mao, current Chinese President and General Party Secretary, Xi Jinping, is intent on consolidating his power to a single man rule. Through a campaign against corruption, Xi has rid the leadership of those he perceives as major threats (think Bo Xilai and Zhou Yongkang). And these officials are dealt with outside of the legal system, through the Party disciplinary committee, with a court of law merely an afterthought and rubberstamp. Public, forced confessions and self-criticisms – now on TV – have made a comeback. And, for the past few years, deaths of dissidents while in police custody appear to be a yearly occurrence – Cao Shunli in 2014, Zhang Liumao in 2015, and now, this Friday, environmentalist Lei Yang (although he likely could not be called a dissident).

Never forget the horror of the Cultural Revolution

Will Xi Jinping return to the levels of violence that existed during the Cultural Revolution? Likely not. But even some regression, no matter how small, is a dangerous step. As Judge Cai’s blog post reveals, the Chinese people suffered tremendously during the Cultural Revolution. They do not need to do so again.

For another poignant story similar to Judge Cai’s, see the New York Times’ re-telling of the loss of Chen Shuxiang’s father and the mere $380 he received in compensation for his death.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email