Truth, Lies or Justice: Defamation in the Chen Yongzhou Affair

The detention of journalist Chen Yongzhou, his employer New Express’s front page editorial pleading that he be set free, and Chen’s subsequent televised confession to accepting bribes and writing false articles against Changsha’s Zoomlion, all the while in Changsha police custody, is, even for China, unusual. But the question is – was it all legal?

Last week, China Law & Policy examined whether Changsha police followed proper procedures in detaining Chen, especially since they went to Guangzhou to find him. Today, we look to the underlying charges – mainly the claim that Chen defamed Zoomlion and thus is subject to arrest. Is defamation a crime?

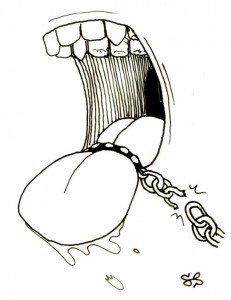

Watch What You Say…..Criminal Defamation is Legal in China

Like it or not, China’s criminal law covers defamation. Article 246 makes it criminal to “publicly humiliate another person or invent stories to defame,” providing a potential prison term of not more than three years. But as Mei Ning Yan stated in Criminal Defamation in the New Media Environment – the Case of the People’s Republic of China, Article 246 covers defamations of actual persons, not corporations.

That is why immediately following Chen’s apprehension, state-run news outlets like Xinhua stated that Changsha police had detained Chen on suspicion of “damaging business reputation,” a defamation-like charge found in Article 221 of the Criminal Law which subjects the defendant to up to two years in prison.

According to Chinese news reports, on September 9, 2013, after over a year of alleged defamatory articles published by New Express, representatives of Zoomlion complained to the Changsha police about the articles. The Changsha police investigated the charges and on October 18, 2013, went to Guangzhou to apprehend Chen (see Stealing Suspects to understand the law surrounding cross-province detention). On October 30, 2013, Chen was formally arrested on charges of damaging Zoomlion’s reputation. The allegations and the charges are all legal under Chinese law

People in Glass Houses…..the U.S.’ Use of Criminal Defamation

While many Americans are surprised to learn that defamation can carry prison time in China, China is not alone in criminalizing defamation. As of 2006, seventeen states in the U.S. still maintain active criminal defamation or criminal libel statutes. While in most states the charge is a mere misdemeanor, one state – Massachusetts – provides for a prison sentence of up to one year. In 1966, in Ashton v. Kentucky, the United States Supreme Court examined Kentucky’s criminal defamation statute and although held it unconstitutional, it was only on the grounds that the use of “disturbing the peace” to define the crime was too vague to pass muster. The crime itself was not a problem; just the way it was defined, or more aptly not defined. The seventeen states that retain a criminal defamation or libel statute have much more clearly defined laws that could potentially pass the Ashton test.

Since the 1966 Ashton case, criminal defamation has rarely been prosecuted. But more recently, there has been a bit of a revival in the United States, at least in examining these statutes intellectually in light of the internet age. Criminal libel and defamation statutes are seen as a possible to deterrent what has become a more common problem in the United States: cyberbullying. In “Kiddie Crime: The Utility of Criminal Law in Controlling Cyberbullying,” Megan Rehberg and Susan W. Brenner note the recent rise in the call to use current criminal law, including criminal defamation statues, to criminalize cyberbullying.

While Legal, the Use of Criminal Defamation is an Odd Choice in this Case

Criminal defamation is a rarely used tool in the United States because individuals and corporations have an alternate option: civil defamation claims. Bringing the case civilly entitles the victim to compensation. For most, especially for businesses, monetary compensation is a lot more rewarding than having the perpetrator sit in a jail cell.

Although an October 29, 2013 op-ed by Ku Ma in the English-language version of the China Daily asserted that there is no ability to bring a civil defamation claim, that is just not true (and might explain why that op-ed has been pulled from the China Daily website although still available here). Since the 1987 adoption of the General Principles of the Civil Law (“General Principles”), where reputation has been harmed, civil defamation claims are permissible under Article 120 for both citizens and “legal persons” (businesses).

Under the General Principles, the victim can sue the perpetrator for the following remedies: (1) to stop the defamation; (2) to restore his reputation; (3) for an apology; and (4) for compensation, both economic and emotional. These remedies are not available under the Chinese criminal law.

Under the General Principles, the victim can sue the perpetrator for the following remedies: (1) to stop the defamation; (2) to restore his reputation; (3) for an apology; and (4) for compensation, both economic and emotional. These remedies are not available under the Chinese criminal law.

And the victim can bring the civil defamation claim in his home jurisdiction. According to the Supreme People’s Court’s 1998 Interpretation of the General Principles, the “consequences of the crime” in defamation cases can be the plaintiff’s hometown. So for a company like Zoomlion – where the provincial government as its controlling shareholder and it is an important economic force in Changsha – bringing a civil defamation charge in Changsha would likely have a close to 100% success rate. According to a 2006 study by Prof. Benjamin Liebman examining defamation cases in China, cases brought in the plaintiff’s home jurisdiction have an 82% success rate. That rate increases to 88% where the plaintiff is also a Party-State actor.

So if you are Zoomlion, why bring the criminal action? Why not go for the civil claims and at least get paid? Prison time for Chen doesn’t necessarily make you whole. And Zoomlion gets the apology either way.

Only Zoomlion knows why it choose to go the criminal route and not the civil one. But in trying to find some rational reason, one can’t help but wonder that maybe Zoomlion wanted to avoid a civil trial. A confession from Chen, held incommunicado in Changsha, would mean that a court would only have a short criminal trial with little testing of the evidence (in China, “plea bargaining” doesn’t avoid a criminal trial, it just shortens it. See here for a detailed explanation). With Chen’s confession, Zoomlion would not have to worry about “truth” as a defense to defamation.

Another alternative theory is that the Party-State wants to send a signal to an increasingly aggressive media: the government is still in charge; that under China’s new president, Xi Jinping, the commercial media will be reigned-in. The years 2008 to 2012 witnessed the central government’s clamp down on a once increasingly vibrant public interest lawyer bar. While still active, that bar is under constant assault. Does 2013 begin the start of a similar and severe clamp down on the commercial media?

But these theories are speculation. Perhaps Chen is guilty of accepting bribes from Zoomlion’s competitor and wrote false articles. The only one thing we know for sure is that Chen’s televised confession and his “trial by television” (as Peter Ford has coined the term) does a disservice to a rule of law. Instead, like the Gu Kailai trial and subsequent Bo Xilai one, the Chinese government has merely continued to demonstrate that for legal cases that would test the system and challenge vested powers, its merely sham justice. Who the Chinese government thinks it is fooling is unclear.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email