The Trial of Gu Kailai – Did the CCP Bite Itself in the Butt?

On Monday morning (Beijing time) the Hefei Intermediate Court will announce its verdict in the murder trial of Gu Kailai (pronounced Goo Kai-lie), wife of Chongqing’s purged Party Secretary and former rising star, Bo Xilai (pronounced Bwo See-lie). The world will be waiting but not because the verdict is uncertain (Gu will be found guilty) or because she will receive the death penalty (likely her sentences will be commuted to death penalty with 2 year reprieve, a.k.a. life sentence); the world will be watching more because this absurd tale of kangaroo justice mixed with seemingly bizarre and inconsistent facts will finally come to an end.

August 9, 2012: The Eight Hour Murder Trial

Gu is accused of murdering one-time family friend and British businessman Neil Heywood in order to protect her son, Bo Guagua (pronounced Bwo Gwa-gwa). While the eight-hour trial was publicized in the Chinese press, the evidence against Gu is flimsy at best. Even the prosecutor’s arguments seemingly contradict the facts and common sense. At the trial, prosecutors argued that Gu was motivated by a motherly (and as presented to the court mentally unstable) need to protect her adult son.

Allegedly, Heywood kidnapped Bo Guagua, kept him in his basement in England, and threatened his safety after a business deal went bust. To

protect her son, in November 2011, Gu allegedly hatched a Tudor-esqe plan to convince Heywood to come to Chongqing where she met him at his hotel room, had him drink copious amounts of wine and tea, watched him vomit and then gave him a glass of water mixed with cyanide. When Heywood’s dead body was discovered two days later, on November 16, 2011, by hotel staff, Gu allegedly convinced his wife in Beijing to cremate the body.

None of this makes sense, at least in terms of justice and accountability. Since 2010, Gu’s son has lived in the United States, attending Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and Politics (he graduated May 2012). At the very latest, Bo Guagua’s “kidnapping” would have occurred in early 2010, when he was a student at Oxford. But wouldn’t Oxford have been aware of a missing student? Wouldn’t a protective mother call the British police at the time to alert them of the kidnapping of her son? Other than Gu’s “confession” and other witnesses’ statements read into the record by prosecutors, no tangible evidence was presented.

Gu Kailai – A Pawn in Her Husband’s Purge?

But this trial is not about sense, justice or accountability. Instead, with its lack of evidence and with its fantastical soap-opera explanations, it is a song-and-dance number put on by the Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”) to explain the downfall of Gu’s husband, Bo Xilai.

Since 2007, Bo has had a successful run as Chongqing Party Secretary. Starting in 2009, Bo lead a popular crack-down on corruption, prosecuting thousands of black market operatives. Under Bo’s leadership, no one was safe; even corrupt politicians were prosecuted. Chongqing, once the bastion of organized crime, had been cleaned up under Bo and its people were very happy.

As Chongqing Party Secretary, Bo also began efforts to revitalize Maoism. Calling on the people to sing “red songs” and for the young to go to the countryside, Bo harkened back to the days of the Cultural Revolution. Bo’s neo-Maoism was criticized in the Western press but was not opposed by all in Chongqing. Namely, the “losers” of China’s economic development benefitted from Bo’s focus on public work projects and subsidized housing for the poor.

In Chongqing, Bo was becoming a powerful politician with an already regal pedigree (Bo is known as a “princeling,” the son of one of Communist China’s founding leaders). By the middle of 2011, Bo had positioned himself perfectly for a powerful, national position with China’s change in leadership set for October 2012. A position on the all-powerful Politburo Standing Committee was not out of reach.

But Bo’s downfall began, not with the November 14, 2011 death of Neil Heywood, but with Wang Lijun’s – Chongqing’s police chief and long-time Bo ally – alleged attempted asylum at the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu. On February 6, 2012, Wang fled to the U.S. Consulate, allegedly fearing for his life and confessing to U.S. Consulate staff the secrets of Bo Xilai’s reign. The U.S. did not provide Wang with asylum; once he left the consulate, Chinese officials boarded Wang on a flight to Beijing to be disciplined by the Party.

On March 15, 2012, Bo was dismissed as Chongqing Party Secretary although retained his position on the Politburo (but not yet the Standing Committee). On April 10, 2012, the Chinese government announced its investigation of Gu Kailai for the November 14, 2011 murder of Neil Heywood and dismissed Bo from his remaining Party positions, effectively purging him.

But did Gu actually kill Neil Heywood? With the minimal “evidence” presented at trial, it’s unclear. It could be that Heywood unexpectedly died while in Chongqing or that someone else killed Heywood and that pinning the murder of Gu is a more pleasant way for the Party to explain Bo’s purge than the actual truth.

Does a One-Party Authoritarian Dictatorship Need to Explain Its Purge?

In the past, the CCP has purged Party leaders without any explanation. But in the case of Bo – with his international stature, relative popularity among the people, good looks, and money – purging him without any explanation would raise eyebrows to say the least. One thing the CCP cannot have as it jockeys its leadership transition, is a public who questions its legitimacy.

The internet, fervent micro-blogging and greater access to information (even if it is government-censored), leaves the CCP susceptible to rumors (or in some cases, to uncovering the truth). Some Party-approved narrative is necessary to explain a popular politician’s purge. Here, Bo’s downfall is his wife’s alleged murder of Neil Heywood. The criminal trial – held in a Hefei, not Chongqing court – adds further legitimacy to the Party’s narrative.

But even more importantly, the trial serves as an important signaling device for China’s internet users. By leaking some information to the government-controlled press from the trial regarding the Party-approved narrative, the Party puts Chinese society on notice as to the acceptable dialogue surrounding Bo’s purge.

But Will the Trial of Gu Kailai Ultimately Bite the CCP in the Butt?

It could be that Gu killed Heywood. It could also be that she didn’t and that her trial is being used to mask the real reasons for Bo’s purge. But

regardless, the flimsy manner in which Gu will likely be convicted gives the appearance of her innocence. The facts just don’t make sense and not just to the Western audience. Likely many in the Chinese audience see this as well (they just know that they can’t talk about it).

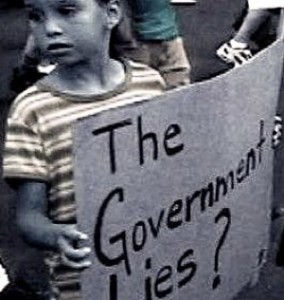

The Party put on this show trial to bolster its legitimacy. But ultimately it’s this trial that will undermine the Party’s legitimacy. The CCP has a serious trust problem with its people – its people know that food safety is flouted with abandon, that government officials’ children get away with murder, that government statistics on air pollution are a lie, and now that something weird is going on within the Party over Bo Xilai. But a people’s trust of its own government is necessary to its ultimate success. Yes, in every country, people question some aspect of their government or their history, but not to the extent that happens in China. Without trust, at some point the government won’t be able to function. So the question emerges, how many lies can the CCP continue to tell before its house of cards comes tumbling down?

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email