Book Review: Philippe Sands’ East West Street

Is there a genocide in China’s Xinjiang province? Are western governments right to declare such an event? Or is this merely a political game? For the past six months, since the United States first declared the Chinese government engaged in a genocide and crimes against humanity against the Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang, it is the questions of whether it is right to call this a genocide, not questions of what can be done to stop the atrocities, that have filled editorial pages of the Western press. Crimes against humanity – an equally serious charge and the charge that resulted in death sentences for the defendants at Nuremburg – raises no one’s interest.1 Why?

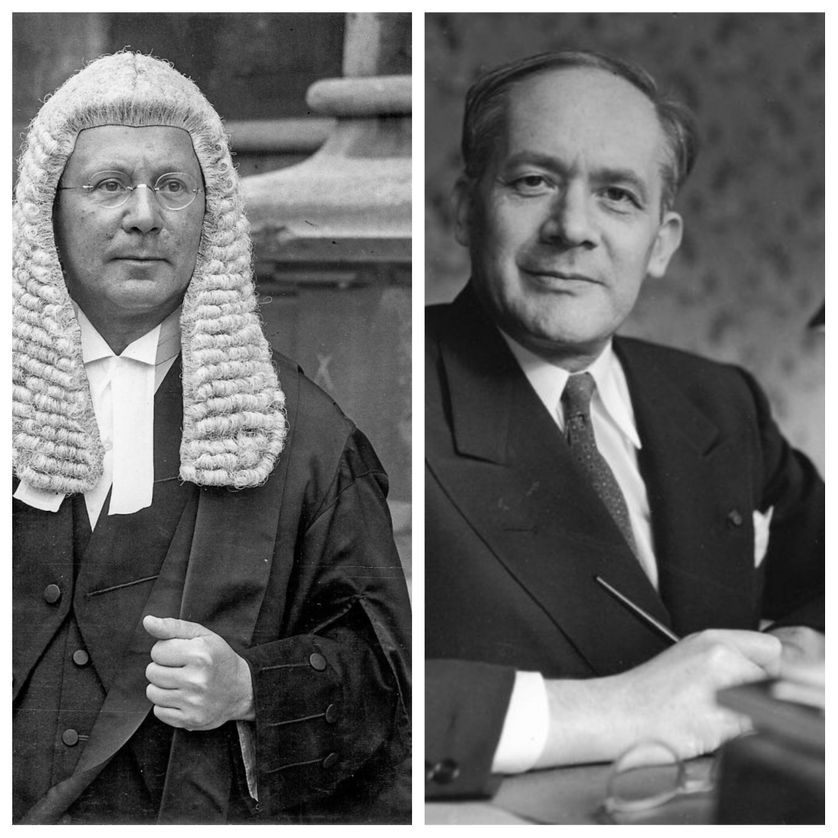

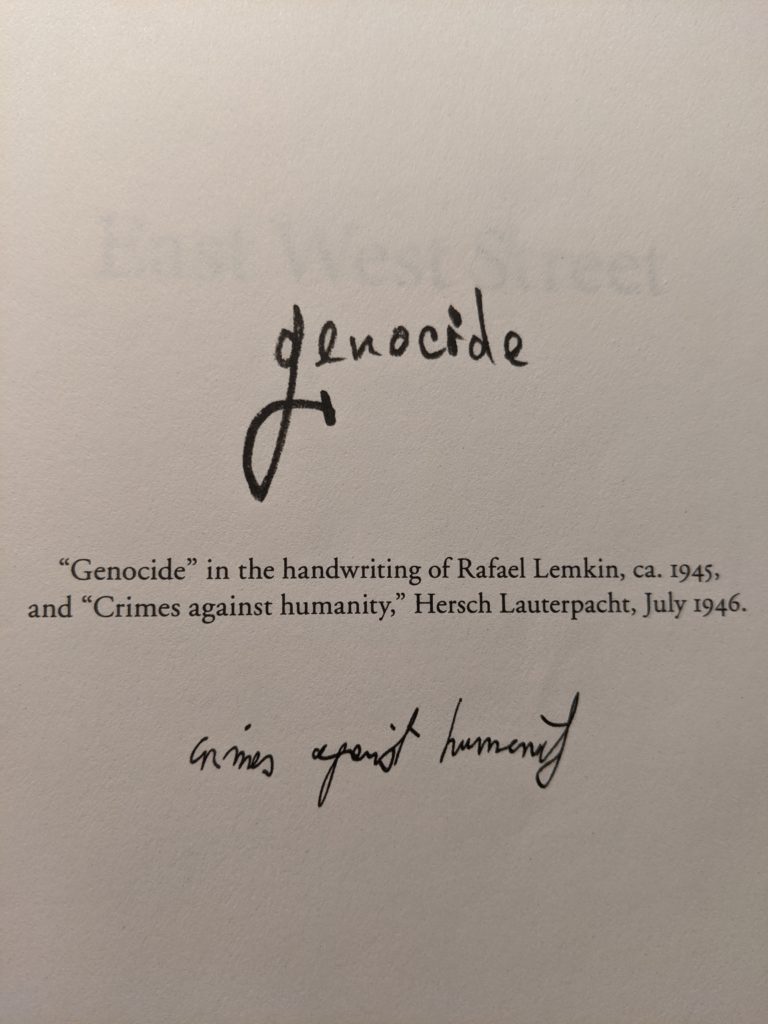

It was with these questions on my mind that I began reading Philippe Sands’ East West Street, a book that tells the story of the two men who created the legal doctrines of “crimes against humanity” and “genocide” after World War II and change the course of international law: Hersch Lauterpacht and Rafael Lemkin. Lauterpacht and Lemkin, born only three years apart at the turn of the 20th century, led similar lives. Both were Jewish; both born in a small town in what became Poland after World War I; both had their legal minds shaped at Lemberg University; both were pretty much their families’ sole survivors after the Holocaust.

And both saw the same problem with the post-World War I world order in which they came of age: an international legal system that promoted state sovereignty above all else. Each country was free to treat the people within its borders as it saw fit and, because of state sovereignty, other countries could do nothing to stop it. For Lauterpacht, the Polish and Ukrainian pogroms imposed on the Jews post-World War I, were the type of violations that demanded humanitarian intervention. Lemkin, in watching the trial of an Armenian for the murder of an Ottoman official who killed his family, could not comprehend how Ottoman Empire officials were left unpunished for the Armenian genocide. The Nazis rise – and its abuses and ultimate destruction of the Jewish population – made it all the more obvious to both that to protect fellow human beings, the world order had to change.

But Lauterpacht and Lemkin would offer different solutions. Lemkin came up with the crime of genocide, the intentional destruction – in whole or in part – of a group of people. For Lemkin, certain people were targeted – be it the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire or the Jews of Europe – because of their membership in a particular group. The law should not ignore that fact and should punish it. For Lauterpacht, it was group dynamics that lead to atrocities – this “us against them” tribalism, be it by the victim or by the perpetrators, is what needed to end. Thus, Lauterpacht created crimes against humanity – the systematic destruction of individuals in large numbers; membership in a group and the perpetrator’s intent were irrelevant. In the short-term, Lauterpacht’s theory won the day – no defendant at Nuremberg was convicted of genocide but many were convicted of crimes against humanity. But it is Lemkin’s theory of genocide that has come to be seen as “the crime of all crimes,” and that has somehow led to crimes against humanity taking a backseat in the global media. We can see this in how the debate about Xinjiang has played out: an almost laser-like focus on genocide at the expense of the charge of crimes against humanity.

While I picked up East West Street to help me understand the current debates about genocide and crimes against humanity in Xinjiang, it was Sands’ description of the post-World War I world order that was surprisingly applicable to present-day China. Since at least 2019, the Chinese government has responded to any foreign criticism of its actions in Xinjiang by claiming state sovereignty: other countries have no right to interfere in China’s internal affairs. In June, in response to a 40-country statement critical of China’s actions in Xinjiang, the Chinese delegation to the United Nations organized a 65-country response that stressed state sovereignty and opposed the “us[e of] human rights as an excuse to interfere in China’s domestic affairs.”

As East West Street makes clear, this type of ideology harkens back to the post-World War I world. It was that world order that allowed the Nazis to pass anti-Semitic laws like the Nuremburg Race Law without any repercussions. It was this idea of state sovereignty that gave the Nazis the belief that their murder of six million Jews was within their rights. And while the Chinese government might pretend that human rights, and its supplanting of state sovereignty, is a Western idea, China has signed and ratified a large number of human rights treaties, including the 1948 Genocide Convention, all of which places human rights above state sovereignty. In fact the whole idea of the United Nations, including its Human Rights Council, is about relinquishing some of that sovereignty when it comes to individuals’ rights.

Unfortunately China is not alone. The fact that it was able to garner 65 countries’ support last week – even if some of that support is bought – reflects a real backsliding in the world. On some level, that backsliding is evident even in the West where countries like the United States (at least under the Trump Administration) and the United Kingdom reject international institutions and beat the drums of nationalism.

East West Street was published in 2016, before the crisis in Xinjiang and before the rise of rampant nationalism in the U.S., the U.K. and other parts of Europe. But reading it now is an important reminder on what we stem to lose and how dark our world can be if we allow state sovereignty to once again dominate human rights. It is imperative that those who fight for human rights also fight against the Chinese government’s demand for the dangerous return of state sovereignty as the governing ideology.

East West Street is also a must read for anyone who wants to witness the mastery of the art of creative non-fiction. Sands describes the legal doctrines that reshaped international law by telling the stories of four men – Lauterpacht, Lemkin, Hans Frank, the Nazi who ordered the murder of all the Jews of Lemberg, and Sands’ grandfather, Leon Buchholz, another Jewish native of Lemberg and the only one of his family to survive the Holocaust. Sands’ painstaking research enabled him to make these four men more than just historical figures, but real people with hopes, dreams and fears: Lauterpacht’s slow realization of what happened to his family as he sat in a Nuremberg courtroom listening to how the Nazis murdered six million Jews; Lemberg’s single-mindedness to get the world to use his new word, genocide; Franks’ pathetic desperation to save his own skin on the eve of a verdict; and Buchholz’ silence to his grandson about all that he lost between 1938 and 1945. Sands makes it humanly clear through the lives of Lauterpacht, Lemkin and his grandfather what the world stands to lose if it allows state sovereignty to ever again supplant human rights.

Rating:

East West Street: On the Origins of “Genocide” and “Crimes Against Humanity,” by Philippe Sands (Penguin Random House, 2016), 372 pages.

Interested in purchasing the book? Considering supporting your local, independent bookstore. Find the nearest one here.

Footnotes

1. One exception is Human Rights Watch and Stanford Mills Legal Clinic’s April 2021 report which declared that the Chinese government’s actions in Xinjiang as crimes against humanity. Further, since publishing this review, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide also declared crimes against humanity occurring in Xinjiang and possible genocide in its November 2021 report.↩

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email