Book Review: Ian Buruma’s Bad Elements – Chinese Rebels From LA to Beijing

You can’t really be a dissident in an authoritarian regime without being a difficult character. These are individuals who for some reason – call it bravery, call it madness, call it no other choice – feel the need to speak out knowing, either consciously or not, that their cause is likely futile and the full force of the authoritarian regime will come down on them like a ton of bricks. As a result, their life often becomes their cause. What happens to these characters when things get so bad that they are forced to flee their country? What happens to their causes?

These questions rose again this past June when Chen Guangcheng, the blind dissident who escaped his illegal house detention in 2012 and made it to the U.S., caused a stir in the media about his departure from NYU. But answering these questions – or at least attempting to – isn’t untraveled ground as one China scholar pointed out in the wake of Chen’s NYU exodus. Back in 2001, Ian Buruma, a Dutch China-hand and journalist, published Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels from Los Angeles to Beijing and this past summer seemed an appropriate time to pick up the book and read it.

Buruma’s Bad Elements begins by looking at the Chinese dissidents – starting with China’s 1978 Democracy Wall Movement through the 1989

Tiananmen student activists – living a new life in the United States. His survey from Wei Jingsheng to Wang Dan and Chai Ling shows a group of people out of sorts in their adopted land. Without access to China, most have given up their cause. Chai Ling, the famous female student leader of the Tiananmen protests is now a successful businesswoman with a Harvard Business School MBA. Same is true of her former Tiananmen colleague Li Lu. He now runs an investment company in New York. Many of the other student leaders just seem lost and lonely.

The pre-Tiananmen/post-Cultural Revolution Chinese exiled in America do not fare any better. Separated from their cause, most have failed to figure out how to remain relevant to the mission back home. Fang Lizhi‘s wife, Li Shuxian, probably expressed the exiled dissident’s predicament best when she told Buruma “[n]ow I am finally free to talk, but there is no one for me to talk to.” Even amongst the exiled dissident community itself, there is little conversation for as Buruma recounts, the splits within the community are cavernous with some dissidents refusing to be in the same room as others. One would think the bonds within the community would be stronger, but as Buruma insightfully details, the personality traits that allows one to become a dissident are not those that allow them to create strong bonds with others. But even in honestly observing the exiled dissidents, Buruma never loses respect for them, reminding the reader that these people had the courage to speak up and that their suffering is likely incomprehensible to anyone else. These individuals carry the battle scars of seeking democracy in a dictatorship and Buruma is always cognizant of this fact.

But Bad Elements‘ most fascinating aspect is Buruma’s attempt to breakdown “the Chinese Myth,” a key tenant of which is that the Chinese are just not made for or currently prepared for democracy; some form of an authoritarian rule is necessary.

Buruma begins this journey to deconstruct this myth in Singapore, a Chinese-based society where the post-colonial government took and maintained power in the most vicious of ways. For those who have never been to Singapore or know little of the details of its history, this chapter is a must read. Singapore is a scary society that holds tight to the belief that this type of rule is necessary in a “Confucian” and “Asian-valued” society. But even with such pressure to conform and unfathomable methods of torture, there are still those in Singapore who choose to dissent. Their very existence in Singapore demonstrates that the idea that democracy is too alien a notion for the Chinese is nonsense.

The experiences of Taiwan and Hong Kong further demonstrates that the Chinese can have democracy, with Taiwan offering the best hope that democracy can succeed in a Chinese society. While Taiwanese democracy is often punctuated with physical assaults within parliament, as Buruma shows, after a period of abusive rule, it has become a rather thriving and real democracy. Hong Kong is similar except that its reversion back to the Mainland and the change in leadership to more Mainland, business-focused executives threatens that democracy. In fact, in Hong Kong, the Chinese myth is beginning to reassert itself, with some prominent leaders stating that perhaps the Chinese people cannot handle full democracy.

Buruma ends his journey of destroying the Chinese myth by visiting the Mainland where shockingly, the belief in the need for a strong

government is not just prevalent amongst China’s intellectuals (who usually are the dissidents), but is a strongly held. It is Buruma’s cab driver who most cogently expresses the desire for democracy, demonstrating that while the intellectual class believes China’s masses are not ready for democracy, those masses sure think they are.

Although Bad Elements is 12 years old, it is certainly not dated and raises issues that are still pertinent. Twelve years later, the Chinese Myth is still very much alive and not just among the Chinese; at times Western businesses prefer to turn a blind eye to the Chinese government’s choice of leadership and instead are easily lulled by the belief of the Chinese Myth.

Buruma believes that democracy is inevitable in China and that it must be brought more quickly than the current (as of 2001) intellectuals appear to want. Even as early as 2001, the Mainland intellectuals, perhaps reminded of what happened in Tiananmen Square, sought to more gradually change China.

But one wonders, who is Buruma – or any non-Chinese – to say that this approach is wrong? Only the Chinese themselves can find their path.

This theory of gradual reform within the system has only gotten stronger in the past twelve years, with current activists like Xu Zhiyong seeking to work within the system.

Unfortunately, the past four years have shown that perhaps Buruma was right to feel frustrated – the Chinese government has also crackdown

harshly on this set of reform-minded activists. Buruma’s suggestion twelve years ago – that the “social stability” which the Chinese government and the intellectuals desire – can never be achieved where a people is ruled by an authoritarian regime – rings more true today than ever before.

Another prescient aspect of Bad Elements is Buruma’s observation that many of the dissidents, those in the US, Singapore, Tawain, Hong Kong and even China, are Christians. This is an occurrence that has only increased over time. Most of today’s Mainland activist profess the Christian faith. Buruma speculates that Christianity is prevalent among Chinese dissidents as it replaces one religion – Maoism and the Party – with another. It’s unclear if that is the reason or if the reason is more because many of the dissidents see Christian values (at least the ones that make it to China) are akin to the rights and democracy which they seek.

But there are aspects of Bad Elements that do show their age, mostly about the exile community. Although slightly dismissive of Chai Ling in Bad Elements

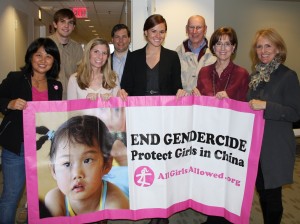

, she has re-engaged with China. In 2010, Chai founded “All Girls Allowed,” a Christian-influenced non-profit that seeks to eliminate the injustices associated with the one-child policy in China. Similarly, Xiao Qiang who is give short shrift in the book, has become an important force in communicating the stories of dissent from the Mainland through his website China Digital Times. Xiao remains extremely relevant to China’s reform movement. And that’s the aspect of the book that Buruma could not have fathomed at the time – the rise of the internet. The internet certainly shapes the role of today’s exile differently than those of years past and perhaps allows the dissident community to continue their connections with activists on the Mainland.

Rating:

— as a result of certain aspects of the book being outdated (which is too be expected from a 12 year old book about contemporary China)

— as a result of certain aspects of the book being outdated (which is too be expected from a 12 year old book about contemporary China)

Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels from Los Angeles to Beijing, by Ian Buruma (Vintage Books 2001), 341 pages.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email