Tipping Point in Censorship?

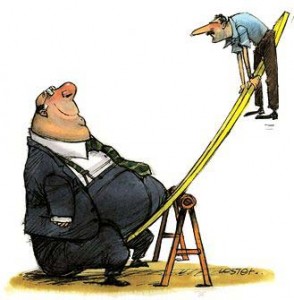

Last November I attended a fascinating talk by Rebecca MacKinnon, guru on all things censored and author of Consent of the Networked: The Worldwide Struggle For Internet Freedom. At the talk, MacKinnon’s focus was on the Chinese corporations that do China’s censorship bidding. MacKinnon noted that China’s internet regulations are not enforced by the government; rather the companies that manage China’s various and extremely active blogs and microblogs are responsible for enforcing China’s online censorship laws and regulations. Yes such censorship leaves these companies’ customers angry, but its worth it for what they get in exchange: an exclusive monopoly that keeps out more sophisticated players like Facebook and Twitter.

But MacKinnon hypothesized that at some point it won’t be economically worth it for these companies to continue to censor. MacKinnon highlighted the complete internet shutdown that occurred in Xinjiang province in 2009 for the entire year. That shut down harmed the local and regional economy. But even that wasn’t enough to cause these internet companies to push back against the government’s internet censorship and control. Instead, MacKinnon mused about the impact that such efforts would have in a more populous region or city, say like Shanghai.

And on Monday it looked like perhaps China reached that tipping point. Monday, June 4, marked the 23rd anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, a sensitive date for China’s Communist Party. On Monday, the Shanghai stock market closed 64.89 points down. But 64.89 is not just any number, it’s the numerical translation of June 4, 1989. As reported in the New York Times, searches for “Shanghai stock,” “Shanghai stock market” and “index” were censored in response to this coincidence.

But can you imagine a country that censors words that are important for commerce? These aren’t searches for “Chen Guangcheng” or other  Chinese activists; those searches would pull results that are obviously about human rights. But searches for business terms? To censor that in a market relies on the speed and effectiveness of the internet is not just plain wacky but bad for business.

Chinese activists; those searches would pull results that are obviously about human rights. But searches for business terms? To censor that in a market relies on the speed and effectiveness of the internet is not just plain wacky but bad for business.

Obviously the Shanghai stock market censorship is not yet the tipping point as internet censorship is still alive and well. But it makes me wonder, are we getting closer? Is what MacKinnon speculated – that eventually the goals of the Chinese government and of the Chinese internet companies will diverge – inevitable? To the extent that you buy into the hypothesis that the Chinese people have “made a deal” with their government – that in exchange for economic security the Chinese will give up some of their political freedoms – is it inevitable that that deal will be broken? The Shanghai stock market debacle hints that maybe in the end its the Party’s own paranoid censorship that will be its death knell.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

You seem to be working on the erroneous assumption that Chinese internet companies are independent, whether they’re listed or not.

They are, like all major undertakings here, ‘arms’ of the government, with embedded CCP officials in senior positions to ensure that the government’s interests are protected.

The government point of view is that ‘the media is the mouthpiece of the party’, and the internet is no different from any other medium.

Which is one of the main reasons that Western – i.e. editorially independent – internet companies have their presence and accessibility so severly restricted here.

Yes, the Shanghai index number example is ridiculous. Will it change anything? No. For the government, the stakes are simply too high.