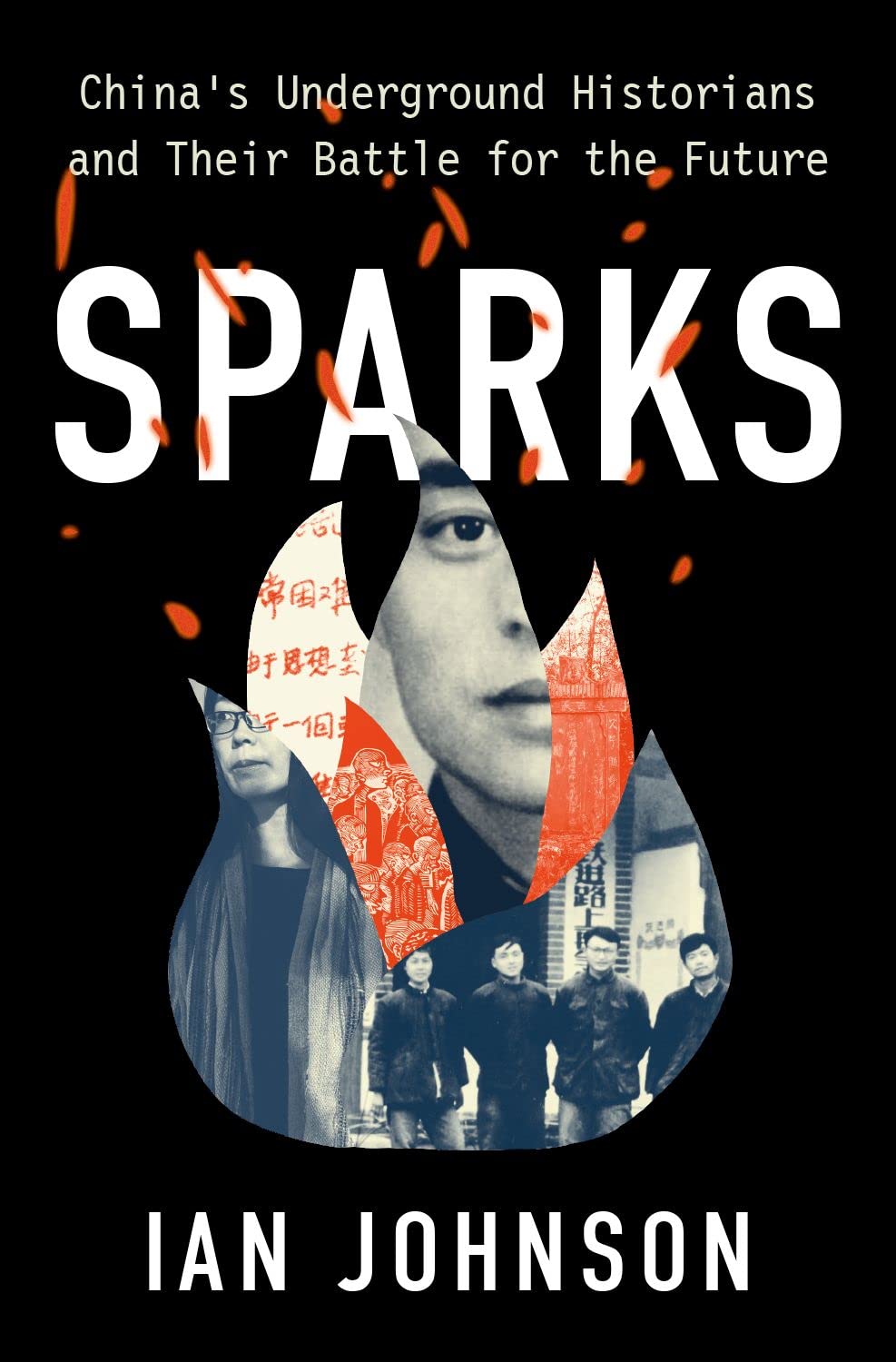

Tiananmen 23 Years Later: An Unknown History?

“For the great majority of young mainland Chinese, the events of the Tiananmen Massacre have never entered their consciousness; they have never seen the photographs and news reports about it, and even fewer have their family or teachers ever explained it to them. They have not forgotten it; they have never known anything about it.”

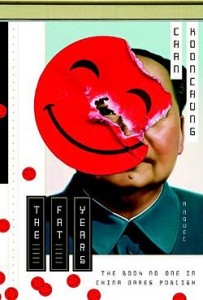

So ends Chan Koonchung’s The Fat Years

So ends Chan Koonchung’s The Fat Years, an allegorical novel set in the near-future Beijing, where China is the only prosperous nation left after the great global economic meltdown of 2008. Most of its citizens are happy – unnaturally so – and fully satisfied with the materialism of their new lives.

But there is a small group of misfits- led by Fang Caodi – that is searching for a missing month from 2008 where martial law was imposed so that the government could bring on the fat years. All remnants of that month have been erased from society’s collective memory: newspapers published during that month no longer exist and no one ever speaks of it. It’s as if it never occurred. Fang and his posse go all over the country, trying to find any evidence of that missing month and trying to find more people like them: people who remember. They find almost no one but then hatch a plan to kidnap a high level government official and interrogate him. They find out about a government intent on guaranteeing that the mistakes of its pass are forgotten and only China’s glorious future is remembered.

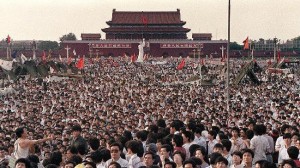

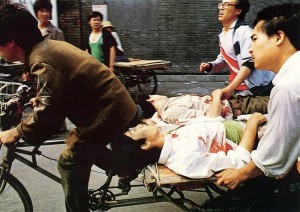

Make no mistake, Chan is not talking about a missing month in 2008. What Chan is discussing are the seven weeks that led up to the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen massacre, where martial law was imposed, high-level Chinese officials ordered the army to open fire on its own people, and hundreds of unarmed student protestors were estimated to have been killed.

On Monday the world will mark the 23rd anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre. But Mainland China will not. Every year, the anniversary of Tiananmen, known as Liu Si in Chinese, is forgotten on mainland China, unless you count the Chinese government’s stepped up security of Tiananmen Square and random detention of activists as a commemorating event.

For 23 years, there has been no public mention of the Tiananmen massacre and aside from hushed whispers among older Chinese, in particular the Tiananmen Mothers who bravely try to keep the murder of their children alive, there is little private discussion of the event. The Chinese government’s 23 years of silence concerning Tiananmen isn’t just denial. It’s been a concerted and fairly effective effort to erase Tiananmen, and the government’s bloody actions on the night of June 3, 1989, from China’s collective memory.

Mainland Chinese born after 1989 largely do not know anything about the events surrounding those seven weeks 23 years ago nor the bloody repression on the night of June 3 into the early morning hours of June 4. To the extent that they have heard anything about it – from a professor who might have supported the students in 1989 or from a family member who was there – their recollections are muddied at best.

Chan’s The Fat Years is a warning: that the Chinese must not forget the past; that they must continue to remember. But that warning is mixed with the reality that perhaps some Chinese do want to forget, especially the young. Compared to 1989, times have never been better. Why rock the boat? Why be bothered with your parent’s history? And that is Chan’s second note of caution to the Chinese: do not be lulled into acceptance by materialism.

But those messages will not be heard in China. In keeping with their efforts to annihilate Tiananmen from collective memory,the Chinese government has banned The Fat Years. In the introduction to the English translation, Julia Lovell notes that the book has still

made its way around dissident circles in Beijing. But dissidents in Beijing are a small, insular group; the vast majority of Chinese will remain unaware. The fact that today’s dissidents and rights activists still remember Tiananmen is one weakness in the Chinese government’s goal and might explain the two-year crackdown on activists.

For the first few years after the Tiananmen massacre, the question was, how long will the Chinese government refuse to investigate the murder of hundreds of Chinese students. Twenty-three years later, now the question is, will the Chinese ever know their own history? As time passes, memories fade, Tiananmen mothers die, and the Chinese Communist Party remains in power, the answer seems to be leaning toward no.

That is why we must never forget June 4, 1989 and continue to memorialize and investigate the events. As censorship increases in China, the western world is ironically becoming the repository of China’s modern history. Eventually, the Chinese people will demand that they be allowed to learn their own history; eventually they will be free to decide for their own what aspects of their history that they want to commemorate and what they want to forget. Eventually, the West’s repository of knowledge will be accessed by the Chinese.

Chan’s The Fat Years should not be read for its literary style. At many points the narrative really slows down and “near future Beijing” is actually 2013, making it difficult for the current English reader of translation to find it even slightly believable. It also appears to peter out toward the end with the main characters just fading from the page. But for the ideas that the book presents about modern day China and its potential future, it is an important read. Especially today, on this anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre.

Rating:

The Fat Years: A Novel, by Chan Koonchung (Nan A. Talese, 2012), 336 pages.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email