U.S.-China Journalist Visa War: Further Undermining A Free Press

2020 was going to be a good year for Josh Chin. He had just become Deputy Bureau Chief of The Wall Street Journal’s Beijing Bureau, had been awarded a prestigious New America fellowship, and received the Gerald Loeb Award for international reporting. His was a career on the rise; a long way from his start as a freelancer.

On February 19, 2020, Chin, in his new role as Deputy Bureau Chief, sat in a waiting room at the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Chin’s boss was on the other side of a closed door, meeting with Ministry officials to discuss whether the Ministry would delay renewing one of their staffer’s soon-to-be-expired journalist visa. Two weeks prior, The Journal had published an op-ed entitled “China the Real Sick Man of Asia” and the Ministry immediately responded, lambasting the author for his arrogance, prejudice and ignorance. Chin and his boss were there to convince Ministry officials not to retaliate against their colleague.

When his boss emerged, Chin waited to hear his colleague’s fate: renewed credentials or delayed visa. Neither his boss told him. Instead, the Ministry had decided to expel Chin and another colleague along with the staffer. Even though Chin’s journalist visa was still valid, he had five days to pack up his life of 13 years and get out.

Since 2012, the Chinese government has used its power over the journalist visa process to censor foreign news outlets. For the Chinese government and the ruling Communist Party, the media exists to serve the Party. “[L]ove the party, protect the party, and closely align [] with the party. . . .” President Xi Jinping told the government-run People’s Daily during a visit to their offices in 2016. To keep foreign journalists in line, the Chinese government has used harassment, surveillance, visa delays and visa downgrades according to the Foreign Correspondents Club of China.

But for the United States, the press is viewed as central to our democracy, its freedoms enshrined in the First Amendment. “Our liberty depends on the freedom of the press, and that cannot be limited without being lost,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in a letter in 1785. Because of this bedrock principle, the U.S. government has been hesitant to retaliate against Chinese journalists in response to the Chinese government’s provocations. But enter Donald Trump, a president who constantly attacks the press. For Trump, rolling back press Chinese journalists’ freedoms was not a hard choice. Instead, it corresponded perfectly with his effort to undermine the press, an institution crucial to our democracy.

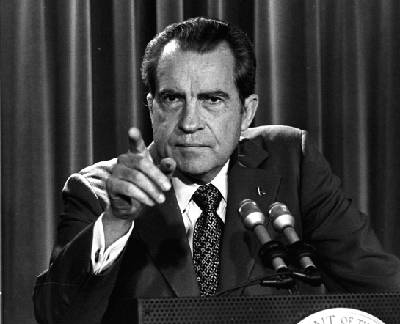

Trump is not the first president hostile to the press. John Adams signed into law the Sedition Act of 1798 which criminalized the publication of “false, scandalous or malicious writing” about the federal government. Richard Nixon privately maintained an “enemies list” and illegally surveilled certain reporters. The Obama Administration prosecuted 11 government employees and contractors for revealing classified information to the press. But Trump’s treatment of the press is different and more nefarious to our democracy. It’s “a systematic effort to de-legitimize the news media as a check on government power,” University of Georgia media law professor Johnathan Peters told the Committee to Protect Journalists last month.

The day Chin was expelled from China, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo condemned the Chinese government’s actions, stating that “[m]ature, responsible countries understand that a free press reports facts and expresses opinions. The correct response is to present counter arguments, not restrict speech.” But on March 2, 2020, the State Department limited the number of journalist visas issued to Chinese state-run outlets to 100, effectively expelling 60 Chinese reporters. The Chinese government responded with more severe sanctions: the expulsion of U.S. citizens employed by The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post. Not long after, the Trump Administration issued its most punitive sanction yet: downgrading every Chinese journalist’s visa to a three-month term from a previous unlimited time period, regardless of whether they work for a Chinese, state-run news outlet or The New York Times. The Chinese government has yet to respond. But expect it to similarly relegate U.S. journalists to a three-month visa or expel all U.S. journalists from China.

Two expelled Wall Street Journal Reporters – Philip Wen (L) and Josh Chin (R) – on their way out of China. Photo Courtesy of Greg Baker / AFP

The Trump Administration’s tit-for-tat diplomacy is a far cry from Pompeo’s “correct response.” Instead, it mimics Beijing’s tactics: restricting speech through the journalist visa process. The United States, once the international champion of freedom of the press, is following the lead of an authoritarian, one-party state. But this should not be a surprise. The Trump Administration’s treatment of the domestic press the past three years reflects its authoritarian bent. Trump repeatedly tweets “fake news” about news stories he doesn’t like and has called the U.S. media “the enemy of the people.” The White House revoked CNN reporter Jim Acosta’s White House press credentials after Trump told him he was a “rude, terrible person.” Trump’s re-election campaign has sued three major media organizations for libel in cases considered “long shots.” These are all pages from Beijing’s playbook, a playbook where the media is subservient to the ruling party.

Some of Chin’s last articles from China were on the emergence of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan. His reporting from early February, as well as that of his fellow, expelled colleagues, exposed the pandemic nature of COVID-19: hospitals overrun with patients; front-line medical workers dying of the virus; mortuaries unable to process the massive number of dead. Their reporting foreshadowed what we would see on our shores a few months later. Even with the Chinese government hiding early facts about the novel coronavirus, U.S. reporters were able to find – and report – the truth. But this truth is an impediment to the Trump Administration’s narrative that China’s lack of transparency prevented it from recognizing the severity of COVID-19. So while the Trump Administration publicly laments the Chinese government’s restrictions on U.S. reporters, it has to know that its retaliatory tactics means that there will be even less U.S. reporters in China. But this may be precisely what it wants.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email