Just for Fun: Uptown & Downtown – Different Perspectives on the Chinese in America

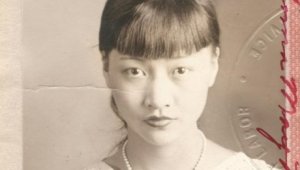

At the NY Historical Society – Photo from American actress Anna May Wong’s identity card that she had to carry with her at all times

It is rare to see an exhibit exclusively on the Chinese experience in America. Rarer still to have two shown simultaneously in the same city. But that is precisely what is happening in New York this fall with the New York Historical Society’s Chinese America: Exclusion/Inclusion and the Museum of Chinese in America’s (“MOCA”) 35th anniversary show, Waves of Identity: 35 Years of Archiving.

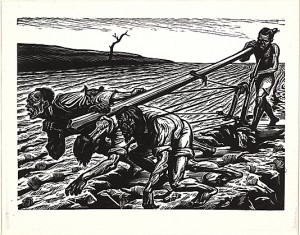

Located on the Upper West Side, the Historical Society is removed from any of the city’s Chinatowns and unfortunately, that removal is felt throughout the show. The exhibition centers on the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, a 1882 act of Congress that essentially barred all but the few Chinese from entering the United States and prevented the naturalization of Chinese immigrants for the next 60-plus years.

Exclusion/Inclusion does a great job of presenting the history of Chinese immigration in America, American’s backlash with the passage of the Exclusion Act, and the Act’s eventual repeal in 1943 (although a quota remained for Chinese immigration until 1965 when the passage of the Immigration and Naturalization Act eliminated quotas). In particular, the show makes clear that “exclusion” in the title of the Act was a misnomer. With the stated goal to keep out Chinese laborers, the Act permitted other classes of Chinese citizens to immigrate: officials, teachers, students, merchants (although not laundry or restaurant owners), and their immediate families (wives and children). As a result, an industry falsifying documents began and the modern U.S. immigration bureaucracy – needed to verify the accuracy of the immigrants’ documents and keep as many Chinese out – was born.

But throughout the show, the history feels whitewashed. While the exhibit is about Chinese and Chinese Americans, little of their voices come

through. Sure the show uses the usual method of quotes and diary passages from Chinese men and women held for years in Angel Island, but it is more didactic than it is inspiring. It isn’t until the end, with a blown up graphic novel of Bronx-born Amy Chin describing the continued impact of the Exclusion Act on her family that the exhibition takes on an emotional gravitas.

The Chinese voice is particularly absent in expressing the community’s role in actually changing the law that impacted it or in shaping its own future. Scant attention is paid to the Chinese-American community’s continued activism in agitating for acceptance as Americans. Instead, the show ends with a feeling that “inclusion” has already happened. There is no mention of the 2011 suicide of Private Danny Chen who, prior to his death, was tormented daily because of his Chinese heritage. No mention is made of the 1982 hate-motivated murder of Vincent Chin whose murderers received a mere three years of probation. These incidents and many others show that full inclusion has yet to occur.

But what Exclusion/Inclusion lacks can be found in MOCA’s Waves of Identity: 35 Years of Archiving. Commemorating the museum’s 35th anniversary, Waves is a modest but compelling show. MOCA, located in Chinatown itself, was very much a community-created institution and it is that sense of community that is felt throughout the exhibit.

Waves is not a lineal procession through history like Exclusion/Inclusion; instead, it is much more innovative. MOCA’s impressive collection of community artifacts, photos and oral histories are laid out by answering a series of questions: “who founded MOCA and why?”; “what does it mean to be Chinese?”; “how do you become American?”; “how does memory become history?”; “where does Chinatown end?” None of these questions are directly answered by the artifacts and multimedia that accompany the section. Instead the viewer is forced to engage with the objects and draw their own conclusions. The McDonald’s Shanghai McNuggets promotion that you might fondly remember from the late 1980s, how do we – and should we – place this in our, shared American history?

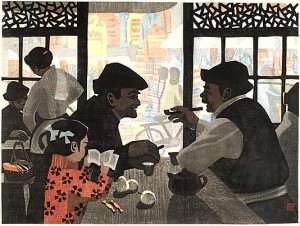

Shop in Chinatown days after Sept. 11, 2001

(c) Corkey Lee – http://911chinatown.mocanyc.org/album/CorkyLee.html

And that is perhaps the biggest difference between Waves and Exclusion/Inclusion. The latter, by its very title, presupposes a separate society that Chinese Americans are either kept from or allowed to enter. Waves on the other hand demonstrates that Chinese American history is – and has always been – as much a part of the greater American history as the American Revolution or the Southern Civil Rights Movement. Perhaps the portion of the exhibit that demonstrates our shared history the most is the section on the impact of the September 11th attacks not just on Chinatown itself which sat in the shadows of the Towers, but also on its people who, like all New Yorkers, saw those anchors of their lives fall before their eyes.

Chinese America: Exclusion/Inclusion, with ads plastered on almost every subway station, is getting the most attention. But if you go see that show, be sure to follow up with Waves of Identity: 35 Years of Archiving for carefully curated exhibit by the community itself that will engage the viewer.

| Chinese America: Exclusion/Inclusion Now through April 19, 2015 Rating:      New York Historical Society New York Historical Society170 Central Park West New York, NY Admission: $19; FREE Fridays 6 pm – 8 pm |

Waves of Identity: 35 Years of Archiving Now through March 1, 2015 Rating:      Museum of Chinese in America Museum of Chinese in America215 Centre Street New York, NY Admission: $ 10; FREE Thursdays All Day |

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email