Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski and Rebecca MacKinnon do not seem to have a lot in common: one is a young, blonde woman born in 1960s America and focused on internet freedom; the other is an older, grayed man born in pre-war Poland who might not really know what a blog is let alone a “microblog.”

Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski and Rebecca MacKinnon do not seem to have a lot in common: one is a young, blonde woman born in 1960s America and focused on internet freedom; the other is an older, grayed man born in pre-war Poland who might not really know what a blog is let alone a “microblog.”

But at last week’s China Town Hall event – sponsored by the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations (NCUSCR) and hosted by Fordham Law School – the general gist of each speaker’s message boiled down to the same point: don’t expect China to follow historical trends; this is a different time, a different place, a different beast and the U.S. needs to quickly recognize this reality.

Brzezinski on China: China is Not Nazi Germany

Brzezinski started the live webcast portion (watch the webcast here) with a very brief synopsis of his role in helping to normalize relations with China during the Carter administration. The briefness of this interlude proved to be a pity and not just because the question and answer portion ended up being sort of lacking.

The history of U.S.-China relations after Nixon’s impeachment remains rather unknown to many. In fact, I would venture to guess that few understand that Nixon’s 1972 visit to China did not normalize relations; normalization was left for another day, and as Brzezinski explained at the China Town Hall, President Ford didn’t believe that he had the mandate to transfer diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. As a result of what appeared to be the U.S.’ waffling, relations between the U.S. and China worsened. However, President Carter’s election in 1976 provided for a new chance at dialogue and with the help of Brzezinski, the U.S. and China eventually normalized relations in 1979 (Prof. Jerome Cohen wrote an interesting essay on the role of Ted Kennedy in normalizing relations – see here).

For the remainder of the webcast – the Q &A portion – Brzezinski proved to be more of a sphinx, giving short,

Deng Xiaoping and Jimmy Carter - 1979

somewhat cryptic answers to most of the questions. As a result, there was plenty of time for question. Perhaps it was a result of the fact that on the same day as the Town Hall – November 16 – President Obama was in Australia announcing the establishment of the U.S. base in that country or perhaps it is what is on most people’s mind, but most of the questions of the night focused upon China’s military ambitions and the U.S.’ appropriate military role in Asia.

For Brzezinski, the U.S.’ current posture toward Beijing – one where China is viewed as a threat – is troubling. According to Brzezinski the U.S. is “pre-judging” the relationship: the U.S. has already determined that China will be an aggressive power and we must develop and deepen our alliances with other countries. But we don’t know if that is true – we don’t know that China is or will be a Nazi Germany; while our guard should be up, we should be open to maintaining a good relationship with China and not isolate it from the rest of Asia.

Brzezinski made an interesting point and supported his argument that China is not as much of threat as we think it is with evidence – China’s military is light years away from being able to compete with ours and China maintains an ambivalent relationship with both Russia and Iran.

But Brzezinski didn’t address some of the very real pressures on the Chinese government to increase its saber-rattling: the military still maintains an extremely powerful role in running the Chinese government and to a large extent, often runs itself; China has become more bellicose in terms of its ability to control portions of the South China Sea; and the lack of communication between the U.S. and Chinese militaries can allow for a small incident to rapidly escalate into a full-blown international one.

In response to one question about rising nationalism in China, Brzezinski pretty much brushed it off (although he did make the important point that the U.S. is guilty of it too vis-à-vis China). While he recognized that it could be a legitimate concern, this nationalism has not been accompanied by anti-American sentiment. This just seemed shocking to me. And, as someone who was in China soon after the U.S.’ accidental bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999, plain wrong. Anti-American sentiment at that time was running high, enflamed by the Chinese media and communicated by many of the Chinese students I met on the Peking University campus that summer and early fall. The anti-American sentiment quickly died down after the U.S. agreed to China’s accession to the W.T.O. in November 1999 but there have been other flare-ups since then.

While Brzezinski is right to state that our approach to China shouldn’t necessarily be guided by outdated models of Nazi Germany or even the Cold War, there are some aspects of China’s rise that precisely because they are different from what we have seen in the past, should cause us to be more on guard.

Rebecca MacKinnon – China’s Internet is Not Egypt’s Internet; It’s A Lot Worse

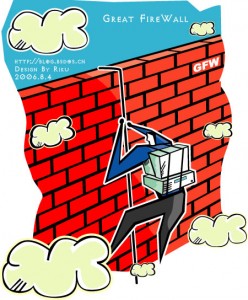

Sites That Don't Make it Through the Great Firewall

Certainly for Rebecca MacKinnon, the live local speaker at the Fordham Law School event, China’s increased nationalism is something on her mind, especially as it pertains to the internet.

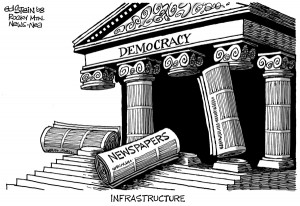

It’s Not All About the Great Fire Wall

MacKinnon started her extremely enlightening talk on internet freedom in China by tearing down some American misconceptions. For most Americans, there is this belief that the “Great Fire Wall” of China is what is preventing internet freedom in China. It is this firewall that completely blocks out websites like Facebook, Twitter, and although not mentioned by MacKinnon herself, China Law & Policy, from being accessible in China. U.S. policy toward internet freedom in China, and the money spent on such efforts, has largely – and mistakenly in MacKinnon’s view – been exclusively directed toward tearing down this firewall; finding ways for activists to circumvent the wall by accessing the internet through a non-China based virtual private network (VPN).

But the Great Fire Wall of China is only one layer in the Chinese government’s web of online censorship. What are more damaging to internet freedom are the vast layers of censorship that occur on the Chinese side of the Great Fire Wall.

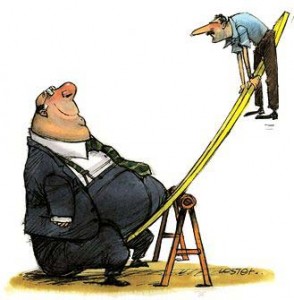

Internet Companies Do the Government’s Censoring

Because of the Great Fire Wall, social networking, blogging and microblogging is dominated exclusively by Chinese companies. Like in America, Chinese citizens can post their thoughts to the internet and communicate with other citizens. But unlike in America, anything that gets too political will be taken down by the hosting company. Through various cyber laws and regulations it is these internet companies – like Baidu and Alibaba – that carry out the government’s censorship of the internet.

If these companies don’t follow the weekly guidance on what content must be taken down, their licenses to run an

Not Just the Police Watching You....

internet company could be revoked, putting them out of business. Thus, under Chinese law, the government outsources its censorship: it issues directives but the internet companies are the ones that are liable if specific content makes it through.

Those companies who do their job well don’t just stay in business, but are rewarded for their vigilant censorship. Every year, the Chinese government awards those internet companies who did the best job censoring a “Self Discipline Award.” And the government is not being ironic.

Because censorship does take time and because the guidance on what content must be removed is an ever moving target, some things do make it past the censors. MacKinnon provided a recent example: the July 2011 Wenzhou train collision. Immediately after the crash, the government issued a statement saying that a train in Wenzhou was struck by lightning. However, with smart phones, many bystanders quickly posted pictures of a train on its side, people obviously injured by something other than lightening, quickly debunking the government’s initial response. That use of the internet but the general public resulted in the government being held accountable and having to report the truth.

But for MacKinnon, these types of opportunities are largely reserved for natural disasters or sudden accidents – things that happen so suddenly that the government hasn’t issued an order to the internet companies about whether such content should be removed.

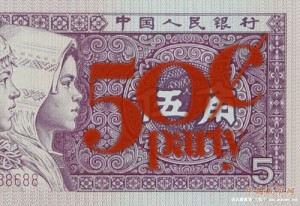

What’s Not Censored? Nationalism and the 50 Cent Party

MacKinnon also made an interesting point about the inequities of censorship in China. It would be one thing if all political speech was censored in China, but it is not. Instead, only that speech that could potentially harm the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is censored; speech glorifying the CCP is provided free reign.

In fact, pro-Chinese government and pro-CCP speech is often ghost-written by the 50 Cent Party, government-hired internet commentators who get paid to post positive content about the Chinese government and the CCP. So while the government is able to stamp out anti-CCP thoughts, it is also able to bolster its own image on the internet.

In fact, pro-Chinese government and pro-CCP speech is often ghost-written by the 50 Cent Party, government-hired internet commentators who get paid to post positive content about the Chinese government and the CCP. So while the government is able to stamp out anti-CCP thoughts, it is also able to bolster its own image on the internet.

Make No Mistake, China is Not Egypt

For those who think that the Arab Spring is coming to a city in China sometime soon, MacKinnon’s message was clear: oh hell no. With such tight controls over the internet, there is no way that a dinner party, let alone a revolution, could be organized through social media like it partially was in Tunisia and Egypt. In the Middle East, there is enough space on the internet to meet like minded people and organize events. In China, that space does not exist as the government maintains a tight grip on speech.

MacKinnon offered one example of the danger in organizing events through the internet or related to free speech on the internet. In 2005, a group of Chinese bloggers organized a national conference in China about blogging – sort of like a NetRoots Nation here in the United States. It gives a chance for bloggers who have communicated virtually to meet each other and provides an opportunity to learn to become a better blogger.

The conference was held again in 2006 and started to become an annual event. Many bloggers began to wonder, is the internet a “special political zone” in the way that Shenzhen was a “special economic zone” in the 1980s? The answer turned out to be no. The last conference was held in 2009; in 2010, authorities went to the leaders of the conference and instructed them not to hold another conference.

Will The Chinese Internet Ever Be Free?

For MacKinnon change rests almost exclusively in the hands of the CEOs of China’s internet companies. Right now,  they have a good deal. They have an exclusive monopoly on the internet. Weibo, the Chinese microblogging site, doesn’t have to worry about competition from Twitter, and Renren, the major social networking site, doesn’t have to ever think about losing costumers to Facebook. In exchange for such exclusivity, what’s a little censorship between friends?

they have a good deal. They have an exclusive monopoly on the internet. Weibo, the Chinese microblogging site, doesn’t have to worry about competition from Twitter, and Renren, the major social networking site, doesn’t have to ever think about losing costumers to Facebook. In exchange for such exclusivity, what’s a little censorship between friends?

But MacKinnon wonders if there will come a point where censorship becomes economically too costly for these companies. If it does, then there could be a change. What would cause that change? That seems unclear. In 2009, because of rioting in the predominately Muslim autonomous region of Xinjiang, the Chinese government took the drastic step of completely shutting down the internet in Xinjiang. That shutdown didn’t last for a few days or a week. That shutdown lasted for almost a year. This wasn’t just an inconvenience; it harmed the local and regional economy. But even this type of drastic action still hasn’t changed any of the internet companies’ approaches to censorship. But perhaps if more of these outages happen or happen in a more populous location, Chinese internet companies might start wondering if aligning themselves with the Chinese government is really worth it.

As of right now, MacKinnon believes that the Chinese government has found a way to maintain its “Networked Authoritarianism.” Chinese leaders at all levels use the internet to get their message out and there are efforts to have broadband reach all areas of China; this is not a government necessarily afraid of the internet; on some level, it has established the structure in place that allows it to use it to its advantages without any of the danger of dissent. On some level, the Chinese government makes a mockery of the generally accepted idea that the internet is perhaps one of the most democratizing tools every created.

Instead, the Chinese government provides a model for other countries on how authoritarianism can in fact survive the internet. The stories of Tunisia and Egypt do not hold true for China.

But as MacKinnon closed out her talk, just when you think you know what will happen in China, something surprises you.

Those interested in learning more about internet freedom should check out MacKinnon’s amazing blog RConversation or pick up her forthcoming book – Consent of the Networked: The Worldwide Struggle For Internet Freedom – when it hits stores at the end of January 2012.

– when it hits stores at the end of January 2012.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email