What’s the T on China’s Social Credit System? – Jeremy Daum Continues – Part 2 of 2

This is the second of a two-part interview with Jeremy Daum, senior research scholar at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, founder and chief editor of China Law Translate and an expert on China’s social credit system. To read Part 1, click here.

Yale Law Senior Researcher & China Law Translate founder, Jeremy Daum

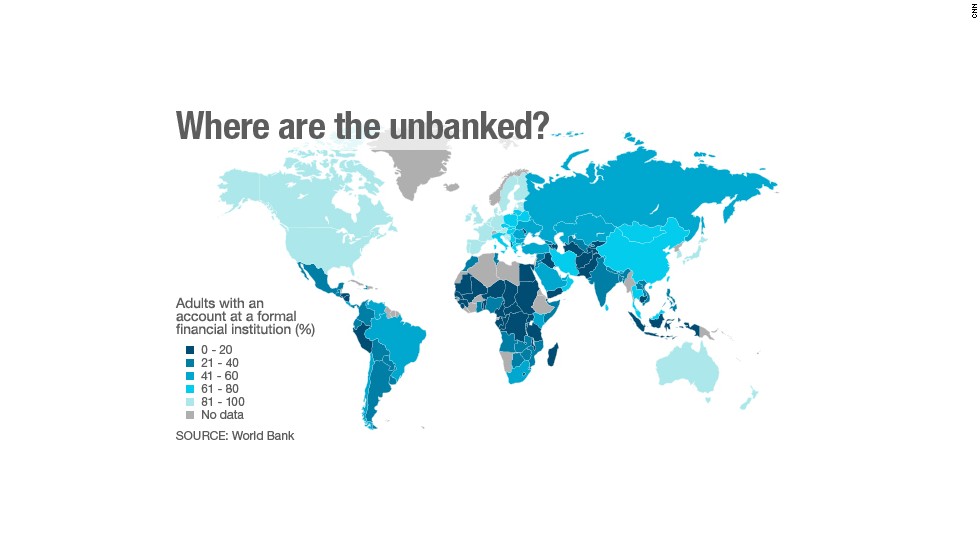

Yesterday, Jeremy Daum, senior research scholar at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, and the founder and chief editor of China Law Translate, started to give us the T – the truth – on China’s social credit system. In yesterday’s interview, we discussed the social credit system’s blacklists and the Western media’s confusion that the social credit system gives a “score” (it doesn’t). Today, we continue our interview with Jeremy, discussing some of the other aspects of the social credit system – the need to create some kind of credit history for China’s large number of unbanked, the influence – if any – of private credit companies, what the real threats of the system are, and how does social credit interact with the surveillance state in a place like Xinjiang.

Read the transcript below for Part 2 of this two-part interview. Or click the media player below to listen (total time – 25:53).

CL&P: The other thing that you mentioned in the beginning about the social credit, the financial credit, the administrative regulatory/blacklist, but also this moral education and I think that’s one of the one that I think a lot of Westerner’s have a hard time getting their head around is this idea of developing a system of trustworthiness and sincerity throughout society. How exactly does the social credit system go about building that?

JD: There’s a lot of different factors, and again I think the part that’s most confusing is that all of this stuff gets grouped in together under the title of social credit. People think that somehow those blacklists and somehow those financial credit things must be feeding into these other components whereas it’s really very siloed sort of stuff. Even though some of it does involve data centralization. Part of the way they do it is with education, straight out education and publicity. Having programs, teaching people about financial credit, but also about moral trustworthiness. The idea that you need to be as good as your word. They’re putting that in school curriculum for children, they’re putting it in outreach things for retirees. They’re creating majors of credit management in the financial sense in universities and they’re just trying to spread that idea.

A winning Model Family in Shanghai

The other part of it though is just taking, trying to put forward role models. Departments, this is part of the red list side of things, are supposed to pick people who they think are doing their job great. Going the extra mile and being above what the law requires and put those forward. Then they get publicized through the media and the like. This is not too dissimilar. . . I have a picture you can put on your website if you want from near my house that is model families and it has the photo is of three families in my neighborhood who have been chosen as role models –最美家庭. And do they get any benefits from that? They probably got a fruit basket or something, but they’re just being put up there as a model. That maybe seems a little hokey or-

CL&P: Yeah, like student of the month.

JD: Maybe to our cynical background it seems silly and I suspect it does to a lot of people in China too. But I think that’s pretty much the extent.

CL&P: Let me ask you, that’s an interesting thing you bring up about financial education and including the morality component in financial education. If it’s about paying your debts I don’t think actually in the United States in my interaction with a lot of the clients I work with, there is an embarrassment for some people in not paying back their debt, and there is also a lack of financial sophistication, especially in low- income individuals because the products are so complicated.

China to teach financial literacy

Do you know to what extent, if China is looking to create a society, you have two thirds of your society that are unbanked, so they don’t really know banking products, they don’t know credit products, how they can be taken advantage by it. Is part of the financial education to teach them the bad parts of banking? I know when my clients come in there’s overdraft fees. They’re paying, even with a Bank of America, Wells Fargo credit card or bank account, yeah they’re not going payday lenders, but they basically have the same effect because of overdraft fees on a $20 purchase they’re paying 300% on not having enough money in your account, overdraft fees and stuff like that. Is the financial education component looking to teach people who haven’t been banking about the dangers of some of these products?

JD: Yes. I don’t think the market here is as complex yet. We’ve seen various attempts to branch out in the peer-to-peer lending situation which is now getting regulated more tightly. In effect yes, I think it’s teaching people the consequences of not being able to pay back your loans, but also how to evaluate a loan and an opportunity and investment as well. The government wants to make money more mobile to make the population more mobile and this is part of its effort to do that.

CL&P: Going back to some of the misconceptions about social credit in the Western press, I think you mentioned before the Sesame Credit. Can you talk a little bit more about the private credit market, developing a credit dossier in the private market vis-à-vis the social credit system itself?

JD: Yes. Sesame Credit, and the reason I’ve written about it at all, is because early on there were some people out there confusing it with China’s social credit system. Even after I’ve written on it and other people have largely cleared that up, people still seem to think it’s a private version of the social credit system and that’s not right either. This isn’t something that’s going to have a public equivalent. What Sesame Credit is, is if we’re looking within those general categories I mentioned earlier of what social credit contains, they’re within that financial portion. And the People’s Bank of China already has a personal credit reporting system.

Alibaba’s Sesame Credit – making credit simple.

And it authorized, in its attempt to reach the great unbanked, it authorized eight companies that were data-rich to develop systems that might eventually become personal credit reporting systems. Among these was Ant Financial affiliated with the Alibaba empire, and there was Tencent, Tencent had one. But the most prominent has been Ant Financial, Sesame Credit. And this does have a score rating and it has a lot of really cute graphics that have an odometer, sort of, green to red. Sesame made a lot of statements early on about how their system was going to tell you if someone was trustworthy. And they talked about how they were going to mobilize their big data to get this going on. I should say right off the back that none of those eight companies that was given permission to develop a functional system received a license ultimately, to create a licensed personal credit report system.

CL&P: So basically the Chinese government said, look we want to see where this goes. We’re going to let you guys experiment, see where it goes, and then they saw where it went and they’re not adopting any of this.

JD: Yes. They created a little incubator to let these try off and they have a lot of natural advantages and data. But, and I think I mentioned earlier with Ant Financial and Sesame Credit they said well the main problem here is your conflict of interests. You’re basing your evaluation of people solely on their use of your products.

CL&P: Right.

JD: The other problem was that it just wasn’t a great indicator. Now, what they’ve done since then is they’ve created an internet lending database. This isn’t bank lending, but this is lending that was happening through the internet and each of those eight companies that wasn’t given a license originally now owns an equal share in this database that is going to be part of – I’m a little shaky on it myself honestly because there’s not a lot out there – but is going to be part of what they try again to create a viable credit score on. We’ll have some other data outside of their own sphere of influence. And these companies will not be sharing data with each other is my understanding. Sorry, they’ll share the 百行 – the credit-

CL&P: The credit report . . .?

JD: Well no-

CL&P: The actual report that shows what you owe?

JD: So they’ll share this common database the government has licensed with the internet data and they’ll all draw on that and then mix that with their own special sauce at home to create their reports. Ant Financial won’t give Tencent it’s commercial data.

CL&P: Okay, so you could theoretically have a different “credit score” from Ant Financial as opposed to Tencent-

JD: And you would.

CL&P: Or if all you do is use Ant Financial products you would have no credit score with Tencent or . . .

JD: How those companies choose to create credit products will be up to them-

CL&P: Will be up to them.

JD: And they might create more than one because part of what the government wants to do in this financial sector is allow companies to start creating more products that would be useful to different people. And so what they create will be up to them.

To go back to Sesame Credit and what it is now. So Sesame Credit, because it doesn’t have an official license, while it would very much like to become something like a FICO score, right now it is really not much more than a rewards or loyalty point system.

CL&P: Yeah.

JD: It’s important to say again, it’s a private scheme, not a pilot for a government scheme. It gives you rewards for using Ant Financial and Ali Pay products and those rewards tend to be things like the waiver of deposits at companies that have signed agreements with Ant Financial, there are no penalties because-

CL&P: They want you just to do more commerce. They’re just encouraging you to get commerce there.

JD: This is a rewards program and some people like it.

CL&P: It’s like United Airlines, you’re a part of that program, the rewards program, so therefore you’re going to try to do more United Airlines.

JD: That’s right. When I ask sometimes people on the street or students that I’ve had who are trying to understand social credit, I ask if they have a Sesame Credit. Sometimes people have to check and see if they do and those who have used it have that same sort of zealot mentality of someone who really loves their Discover card. It’s not a thing. Now that might change someday as it grows.

In most places in the U.S., job applications require a credit check. Even for low-wage employment.

CL&P: As we were talking about what the Bank of China has which is basically … In the United States you can go to annualcreditcheck.com or whatever and you can pull your credit report and it just lists what your debts are, it doesn’t give you the score. It sounds like that’s what Bank of China has. I know in the United States there is a tremendous amount of criticism about our credit reports. And again our credit reports and our credit score, most states in the United States do not outlaw the use of credit report pull to get a job, even if it’s not affiliated with anything related. To get a job at McDonald’s in most states, I think New York City is one of the few cities where they’ve banned the box, but you have to agree to allow them to pull your credit even though you’re just wiping the floors in McDonald’s.

There’s a lot of criticism of credit reports in the United States because it doesn’t allow people . . . it’s only about your debts, it’s only about your credit cards, it’s only about your student loans. It’s not about anything good you’re doing, like that you pay your rent on time. So rent doesn’t appear on your credit report. And then a lot of these cards, like the Rush card which is targeted toward people who are unbanked, if you make payments on that it doesn’t, again, appear on your credit report. Only if you stop making payments does it appear so it’s only negative. Has the Bank of China in looking at credit report and what they’ve created on the national level, have they looked . . . Are they just adopting what the United States has, which is definitely not a perfect system, or are they looking to be more holistic and to help people who generally are unbanked get a good credit report by putting their rental income that they’re current on, something like that.

JD: I’m not honestly sure how they go about calculating the scores. My colleague Jamie Horsley has spent more time looking at these issues. I’ve seen a few reports that come out of it, but I’m not clear. I would say as a general rule while the US and other international foreign models have undoubtedly inspired a lot of what’s happening with the idea of credit reports and even a credit economy, nothing remains unchanged. It will be the “with Chinese characteristics versions.” I think the goal, of course, is to have people with good credit, but there is also this strain of wanting to punish the people who are dishonest that you hear in all the rhetoric and it wouldn’t surprise me to hear that some of that’s there.

CL&P: In concluding, so it seems like the social credit system, I mean it’s a fascinating, fascinating thing what they’re trying to do. I think it’s maybe not all scary. I think there’s a lot that does need to be done helping people get better credit for your economy and stuff. But what do you think is. . . I mean but there is things . . . I mean it is going to a level of knowledge about people that to us as Westerners is really scary. What do you think are the things that people should be . . . that the Chinese government and the Chinese people maybe should be looking at to be a little nervous about?

JD: Yeah, so there’s a few things. The first is something that’s already happening which is the real name systems. This is a phenomena that I think a lot of governments are dealing with trying to end data islands by connecting all of this data that the government collects. The government-created data in China is known as public social credit information. Public in the sense of government, not private, not market. I think that anonymity in some aspects of your life, not having all of your data linked is important. It’s not just important for political dissonance and dissent, it’s important for people with unpopular opinions and unpopular lifestyles.

The benefits of anonymity on the internet

The homosexual community might not want the data that they use in their personal life being somehow mingled with the other data. Now in theory it’s only the government that has any access to this data and there wouldn’t be much purpose for mixing everything together. I don’t want to imply that there’s a question about your sexuality in there, but if all of your internet access is done through a real name registration system and all the platforms that you log onto have to have a real name registration, then any sites which requires a login is going to have it and that creates quite a decent profile of a person’s personal life as well, if not to mention, purchasing histories, et cetera.

I think anonymity is important for protecting people, not just in terms of privacy, but in terms of freedom from discrimination, freedom from persecution. In this society if you’re a Christian it could be an issue. There are always going to be groups that aren’t popular in a community and you should be able to have access to things that don’t hurt people without having to make it public. The other question is, like you said, there is a sort of tendency of people like you were talking about in the US with the credit stores we have, to want to generalize beyond this and to want to take a rating in one area and extend it to all other areas. Criminal records are another thing in the US where a criminal record, or even a record of an arrest where you were later exonerated, can be something that can really follow you for quite a long time.

CL&P: I mean even . . . I think even in the world I work you have a blacklist for tenants who have been sued, who are largely low-income in New York City. And regardless of whether they’ve … the action was frivolous brought by the landlord, they’re still on this blacklist. And unless they’re sophisticated enough to demand that they get taken off the blacklist, they’re on it and then they can’t rent another apartment for five years. And granted it’s a blacklist that is created by a corporate . . . like corporations go in and they review and they create it and then they sell it, but it is still very, very damaging.

JD: And that’s exactly the sort of system that shows the right kind of problem, is that people are always looking for shorthand to rule out. Anyone who’s ever done hiring or admissions knows that you can’t holistically consider every situation so if there is a blackmark of any kind, even if it turns out it’s based on some sort of an unfair rule system or a faulty premise, you’re going to rely on it to some extent.

The other thing that I think with China’s system that’s important to remember is while I’ve said that the administrative regulation part isn’t so much new or bad as social credit because all it’s really doing is enforcing legal obligations, existing laws. Just that something was in an existing law doesn’t mean it’s good. Better enforcement of bad laws is a problem. Generally speaking enforcement of laws is desirable, but if your law is already unfair that can be an issue. And there are laws in China that I disagree with.

There are limits on the freedom of speech that go beyond anything I can tolerate and other areas as well of course. So that becomes a real issue. This enforcement might work. There is still a fear that these joint punishments will eventually extend to things beyond just judgment defaulters. And judgment defaulter’s already a pretty broad category given that any administrative agency is seeking enforcement on its administrative penalty can go to a court to get an enforcement judge. The concern would be that they try to mobilize this massive array of penalties against people for other types of violations. Essentially making a sort of outlaw system where if you failed to follow the rules then the society is no longer protecting you, you’re now on the outside. Now that doesn’t seem to be happening now, but that is the direction that some people fear. But even with what is happening now, with the real name systems, the tendency of people to overgeneralize and the fact that we’re enforcing laws that aren’t great to begin with, it could be really problematic.

CL&P: How does social credit interact with some of the privacy issues, some of the surveillance issues that we’re seeing?

JD: One thing that surprises a lot of people is how much ink is spent in the social credit regulations aimed at corporations and at people on privacy. A lot of it discusses how information has to be protected from outsiders. Like all privacy discussion in China’s criminal law, China’s regulatory laws in general, it always talks about duties of confidentiality, but always assumes this doesn’t sort of apply to the government. Police are supposed to protect confidential information that they come across in investigations. But you don’t get to protect that from the police. This is sort of the same thing in the social credit. There’s actually a lot of discussion about making sure that your personal information isn’t abused, sold to people, or transferred to third parties, but the government has few qualms about gathering it up.

Enough cameras? China’s surveillance state.

It’s worth pointing out here another thing which is a lot of people seem to mingle parts of China’s surveillance apparatus as a whole with social credit. These aren’t necessarily the same systems. Social credit for sure is part of the way of keeping tabs on people in China. It has these administrative permits and administrative punishments in it primarily and also this lending information and financial parts. It’s certainly part of that, but the police also have their own systems that involve the cameras we see on the street. That involve the ability to access computers and networks.

This is part of why when I hear discussion of this being the totalitarian control through social credit, I’m like “China actually has plenty of very blunt, straightforward tools for control.” And you only need to look at Xinjiang to see that. When China has a problem that it wants to deal with it usually has few issues with taking a direct approach to resolving it. Despite appearances, I think China’s actually pretty transparent about what the goals of social credit are and what the goals of surveillance are.

CL&P: When you say Xinjiang, look at Xinjiang, is that to exemplify the surveillance state or is there anything going on in there with social credit?

JD: I don’t think it has much to do with social credit, I think Xinjiang shows you exactly how blunt and direct a tool China can use when it wants to resolve a problem quickly. Here we have large numbers of people being detained. Is there a legal basis? Shaky at best. It’s an end justifies the means situation, where they’ve decided that they’re going to do this. Social credit I think is really about building institutions, and China . . . the point is that China has plenty of tools at its disposal for social control and social management.

CL&P: And Xinjiang is the example of that?

JD: It doesn’t need to create new ones.

CL&P: To what degree, I mean in your learning about the social credit system here in China, I mean this is a huge amassing of data in one place and to me it’s not clear that other countries are not going in that direction. Yes, Facebook has a lot of your data, but what you brought up about the gay community . . . a lot of the stuff if you wanted to find out you can just look at people’s friends, Facebook does all these algorithms, figure out what is your thing. Granted it’s to target advertising. But to what extent do you think other countries, other governments will be looking at country, at least in the amassing of data on their people?

China’s social credit system – too much data to be useful?

JD: I think it’s less looking about China than recognizing the fact that we simply create more data now than ever before. Everything we do now has records and we do things through automated information tech systems. I think how every society, let alone every country deals with that is really one of the defining issues right now. In the US, we seem primarily . . . we’ve had our share of government surveillance scandals, but primarily we’re letting corporations deal with the data and deciding when to limit corporation’s collection of data. Europe has taken a harder line in the interest of privacy rights against corporations.

In China, it’s no surprise that the government is taking the lead on it over corporations. The government is trying to harvest all of its data. The question is what do you do with the data and that’s a technical question but also a policy question. I’m a layman for data science but it seems to me that you’d actually start gathering all this data, have way more data than would be useful to you and it would be really hard to analyze. But I’m sure for specific purposes you could start to find useful things.

CL&P: Going back to China what’s next on the horizon for social credit, what should we be expecting in the next six months –

JD: In the next six months well –

CL&P: To a year.

JD: We have a plan through 2020 that tells us what’s going to happen and within that there’s specific dates. For people who are interested in what’s going to happen to individuals and individual credit-worthiness which is part of that social credit plan, we’re seeing more and more provincial level governments putting out their plans which have timelines in them of what will be done. Mainly it seems to be focusing on the reputation of people in key professions. Doctors, travel agents, people who really effect a lot of other people’s lives. We’ll see I think regulation in those, and I think what it’ll mainly take the form of is the people who have violations of the rules in that field are going to be banned from working in that field for a period of time. But I think we’ve already seen . . . we’re well into that 2014 through 2020 phase and I think we’re already seeing the shape of things that are coming out.

CL&P: All right, well thank you very much, Jeremy, for giving us the T on social credit. We’ll probably be following up with you. Your blog has been great, China Law Translate has been great with a lot of the translations and analysis of social credit so thank you very much for that. Yeah, we’ll be keeping tabs on you through social credit.

JD: Thanks Elizabeth.

To read Part 1 of this two-part interview series with Jeremy Daum on China’s social credit system, click here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email  This is the first of a two-part interview with Jeremy Daum, senior research scholar at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, founder and chief editor of China Law Translate and an expert on China’s social credit system. To skip to Part 2 of the interview series,

This is the first of a two-part interview with Jeremy Daum, senior research scholar at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, founder and chief editor of China Law Translate and an expert on China’s social credit system. To skip to Part 2 of the interview series,  CL&P: Okay, so it’s just to promote positive behavior and not necessarily to punish negative behavior. It would just be in this sphere of charity work, doing good work?

CL&P: Okay, so it’s just to promote positive behavior and not necessarily to punish negative behavior. It would just be in this sphere of charity work, doing good work? So far, that hasn’t panned out in China. Where the systems, including Sesame Credit run by Ant Financial, that have tried to create an alternative evaluation of a person’s credit as a borrower, ultimately it didn’t seem to be a good indicator of whether they would be good at returning debts and they had a conflict of interest where they were basing it mainly on how much was spent on their own products. That made it even more unreliable. But beyond the financial sector, there is a trust crisis in China. One example that I like to bring up is a terrible story that happened a little while ago at a kindergarten here in Beijing, that I think

So far, that hasn’t panned out in China. Where the systems, including Sesame Credit run by Ant Financial, that have tried to create an alternative evaluation of a person’s credit as a borrower, ultimately it didn’t seem to be a good indicator of whether they would be good at returning debts and they had a conflict of interest where they were basing it mainly on how much was spent on their own products. That made it even more unreliable. But beyond the financial sector, there is a trust crisis in China. One example that I like to bring up is a terrible story that happened a little while ago at a kindergarten here in Beijing, that I think

CL&P: So you can still be Bunny Honey.

CL&P: So you can still be Bunny Honey. CL&P: That would be the industry blacklist?

CL&P: That would be the industry blacklist? JD: Here it’s a little different because it’s not just punitive. It’s not just you get a fine for your securities violation and you can’t ride planes, that’s your punishment. It’s coercive, you can get off of that by paying the fine. It’s meant to make you do something. The most famous example of this and the most commonly confused with being the entire social credit system is the court judgment defaulters blacklist. Part of this is a legal jargon problem that people have mistranslated it. What it literally should be is a list of people who have defaulted on obligations from an enforcement court. What that means is that an enforcement division of a Court has issued a ruling that says, “You have either failed to perform on a court award at a civil trial or you were given an administrative punishment, didn’t pay that fine, didn’t act on it.” Then the administrative organ went to the Enforcement Court and got a court judgment saying-

JD: Here it’s a little different because it’s not just punitive. It’s not just you get a fine for your securities violation and you can’t ride planes, that’s your punishment. It’s coercive, you can get off of that by paying the fine. It’s meant to make you do something. The most famous example of this and the most commonly confused with being the entire social credit system is the court judgment defaulters blacklist. Part of this is a legal jargon problem that people have mistranslated it. What it literally should be is a list of people who have defaulted on obligations from an enforcement court. What that means is that an enforcement division of a Court has issued a ruling that says, “You have either failed to perform on a court award at a civil trial or you were given an administrative punishment, didn’t pay that fine, didn’t act on it.” Then the administrative organ went to the Enforcement Court and got a court judgment saying-

CL&P: – Bad acts. So to what extent is this creating a new liability for those people, or have you always been able to pierce the corporate veil under Chinese law?

CL&P: – Bad acts. So to what extent is this creating a new liability for those people, or have you always been able to pierce the corporate veil under Chinese law? CL&P: If you were let’s say the CEO of corporation X, corporation X doesn’t pay because corporation X is basically bankrupt, you’re on the No-Fly List, you can essentially petition, would it be the court or would it be. . .this is for the court default judgment blacklist. You can petition say look, I don’t have, my corporation doesn’t have enough money, I don’t have enough money, can you please take me off. Is that it?

CL&P: If you were let’s say the CEO of corporation X, corporation X doesn’t pay because corporation X is basically bankrupt, you’re on the No-Fly List, you can essentially petition, would it be the court or would it be. . .this is for the court default judgment blacklist. You can petition say look, I don’t have, my corporation doesn’t have enough money, I don’t have enough money, can you please take me off. Is that it?

But in blaming these elusive, foreign, anti-China forces, the Chinese government ignores the real reason why these civil rights activists exist: the injustices in Chinese society. It is Jiang’s own life that is a testament as to why the Chinese government’s efforts to suppress these civil rights activists will ultimately fail. For a

But in blaming these elusive, foreign, anti-China forces, the Chinese government ignores the real reason why these civil rights activists exist: the injustices in Chinese society. It is Jiang’s own life that is a testament as to why the Chinese government’s efforts to suppress these civil rights activists will ultimately fail. For a

While alarming, on some level Shi Fulong is lucky that the op-ed does not cite more although he is certainly bordering on the danger zone. Likely in an attempt to contain China’s civil rights lawyers, in the past couple of years, the Chinese’s government has sought to penalize and contain the zealous advocacy that is required of lawyers, especially civil rights lawyers. In the Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) recent

While alarming, on some level Shi Fulong is lucky that the op-ed does not cite more although he is certainly bordering on the danger zone. Likely in an attempt to contain China’s civil rights lawyers, in the past couple of years, the Chinese’s government has sought to penalize and contain the zealous advocacy that is required of lawyers, especially civil rights lawyers. In the Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) recent